Her Own London

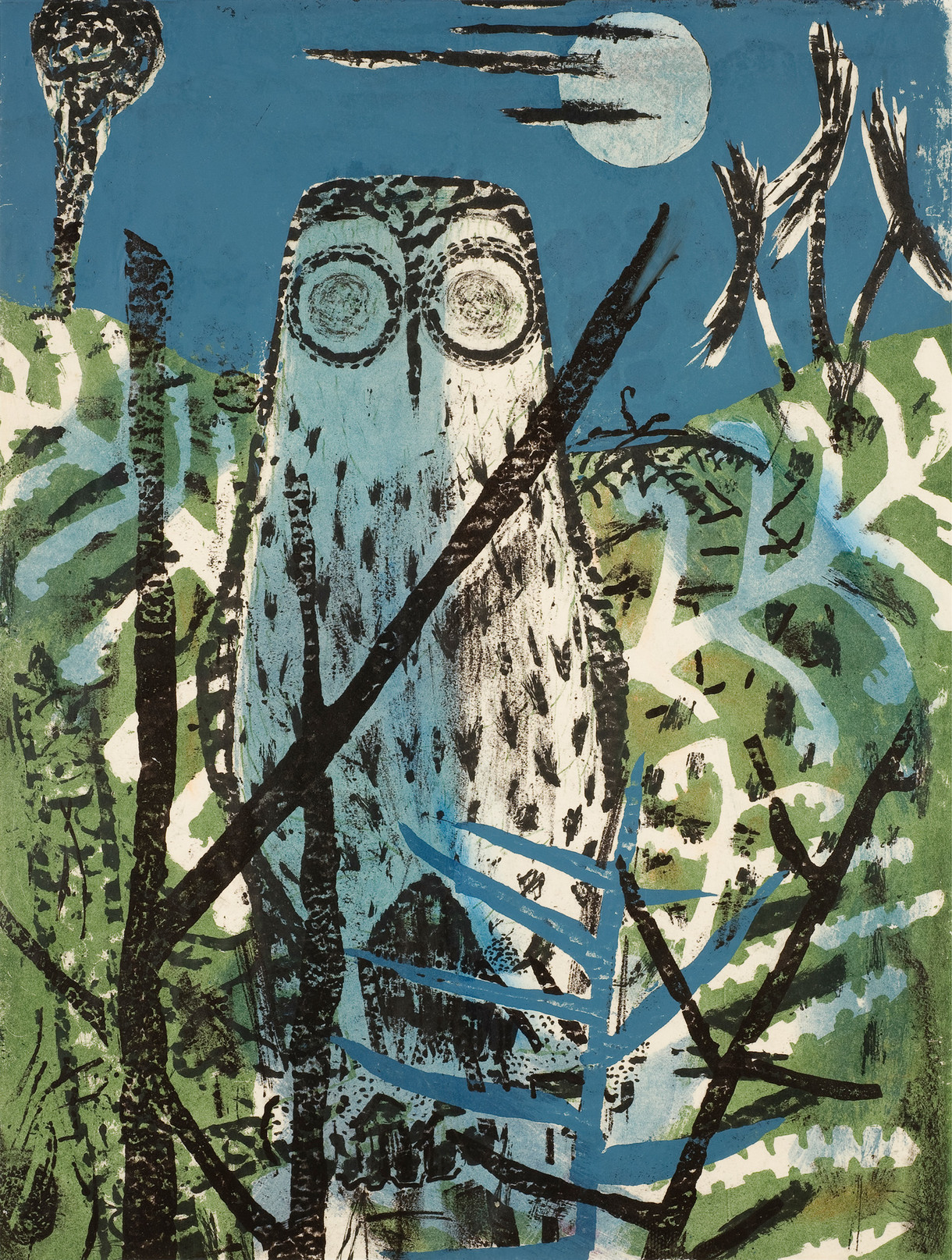

Juliet Peter Poodles 1954. Lithograph. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1992

I laughed at your note. Our packing was not done until the last minute of the 11th hour, and when we at last got onto the train we could only think how lovely it was to do nothing and think about nothing. However, by now we realise we are really going to England. After 17 days at sea, out of sight of land, N.Z. seems as if it was in another universe.1

Juliet Peter wrote to her friend Jean on 17 August 1953 from the cargo liner RMS Rangitiki (then approaching the Panama Canal). On board with her was Roy Cowan, whom she had married the previous year after meeting while they were both employed as artists in the Department of Education’s School Publications branch in Wellington. There, they provided illustrations for a range of publications, including the New Zealand School Journal, which had been recently revamped to include more New Zealand content. It was creative and reasonably paid work, and popular with many of New Zealand’s best artists at that time, but the newly minted Mr and Mrs Cowan were giving it up to try their luck on the other side of the world. FTN-2 Roy had been awarded a scholarship to study art in England and they were headed there together.

It wasn’t Juliet’s first trip to England. At eleven years old, she had been taken to Kent by her elder sister following the death of her parents. She lived there for almost a decade, spending some time at boarding school, until she returned to New Zealand in 1935 to attend art school at Canterbury College in Christchurch. She had also spent a year in London in 1951, attending classes at the Central School of Arts. She learned lithography and also studied life drawing (taught by Mervyn Peake, the writer, artist, poet and illustrator best known for his Gothic fantasy novels about the inhabitants of the decaying Castle Gormenghast).

This time, Roy was enrolled to study printmaking, drawing, book design and art history at the University of London’s Slade School of Fine Art, while Juliet would study lithography (under Alistair Grant) and ceramics part-time at the Hammersmith School of Building and Crafts. The latter was a characteristically practical choice. The couple shared a belief that the best art combined creativity with craftsmanship, and lessons at Hammersmith were oriented towards hands-on practice rather than theory. Located in Lime Grove, Shepherd’s Bush, it incorporated a series of studios in which textile design, ceramics, sculpture and printmaking were taught, as well as a number of trades, from plumbing and welding to bricklaying and plastering. The close proximity between the workshops was designed to encourage students to learn across disciplines.

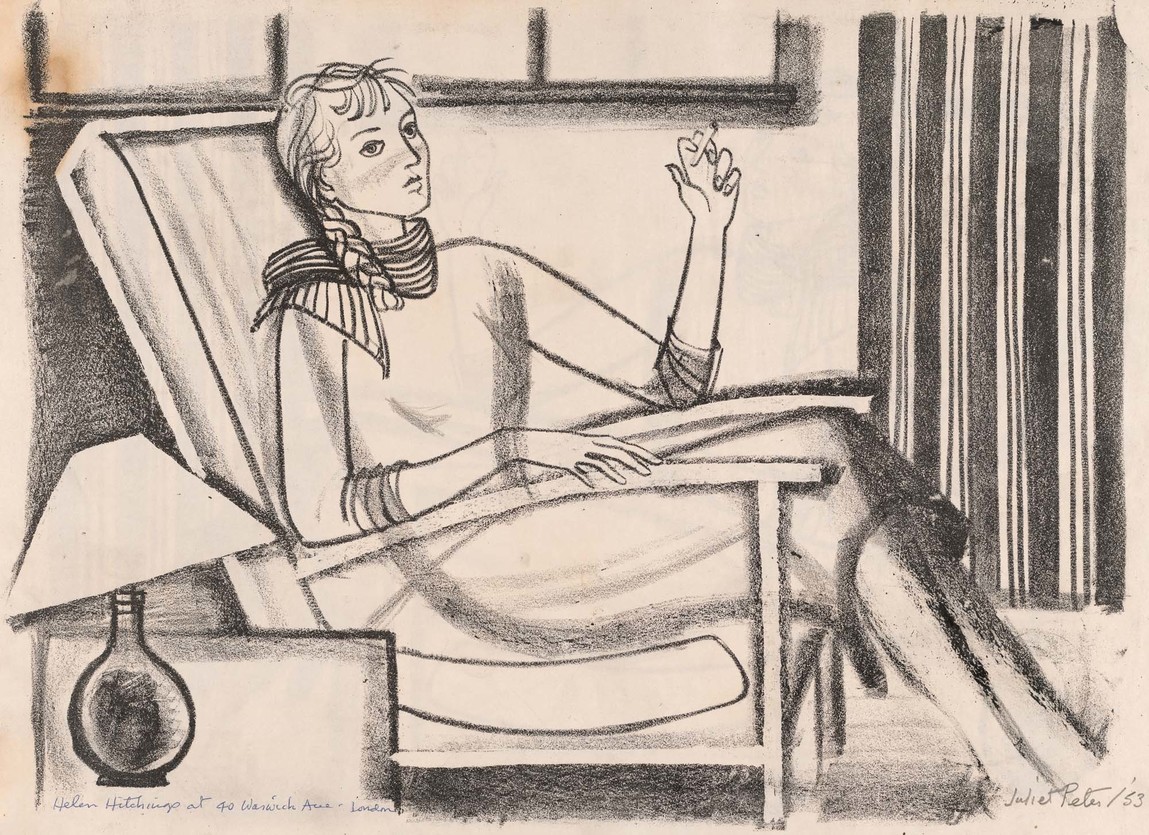

The London the Cowans arrived in was a city of contrast and transformation. Still reeling from the recently ended war, and with much of the central city devastated by bombing raids, it was nonetheless re-emerging as a modern centre of culture and fashion. At first, they stayed with another New Zealander, Helen Hitchings. They knew her from Wellington, where she had opened New Zealand’s first modernist dealer gallery in a converted warehouse space. Hitchings had cultivated a deliberately relaxed atmosphere, inviting visitors to smoke and drink coffee while appreciating works by painters such as Evelyn Page, Rita Angus, Colin McCahon, Toss Woollaston and Douglas MacDiarmid. Her gallery also showed pottery, textiles and furniture (the latter designed by the Modernist architect Ernst Plischke). As Juliet related later, Hitchings had arrived in London with an ambitious plan:

She conceived the scheme of making a collection of New Zealand art of that period and taking it with her to London and finding a gallery to show it. She thought it would be easy – it wasn’t – but she was still there when Roy and I first arrived in London. She was a great help because she had an apartment in Oakley Street in Chelsea and we stayed for our first week or two with her in London.FTN-3

When the Cowans found an apartment at 40 Warwick Avenue in Maida Vale, Hitchings visited them there, and Juliet’s portrait of her captures a strong sense of her personal style and, perhaps, a trace of disillusionment.

Juliet Peter Afterthought—Helen Hitchings, London 1953. Lithograph. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1996

Maida Vale is famous for its large late-Victorian and Edwardian blocks of mansion flats, and the Cowan’s flat was a short walk from Hyde Park and Little Venice, providing Juliet with an ever-changing panorama for people-watching. Their landlady, whose black dog Lulu was later immortalised in one of Juliet’s lithographs, taught ballet dancing downstairs: “At night, we could hear the trains pulling in to the station, and then in daytime, we’d hear this strange ballet music. It was very entertaining.”4 Though somewhat reserved in character, Juliet was a natural observer, accustomed to filtering her experience of the world through the lens of her artmaking. “Very early in life I discovered the fascinating marks that a pencil could make on paper,” she once said, “drawing became my delight – and it still is.”5 Growing up, she drew the animals on the family farm at Anama, near Ashburton, and in Kent she had earned pocket money selling her sketches of the neighbours’ houses. While at Canterbury College, her talent for caricature came to the fore, as she skewered lecturers and prominent students with a witty, occasionally astringent, eye in sketches published regularly in Canta magazine. When she took up war work in the 1940s as a land girl on Rydall Downs sheep station, near Oxford, Juliet sketched her fellow farm workers in action and repose. Gaelyn Elliot, grand-daughter of the station owners, remembers her drawing on the backs of matchbooks in the kitchen after meals: “she caught the whiskery old great-uncles to a T.”6 As Juliet’s letters from aboard the Rangitiki make clear, she was always alert to unusual subjects and spectacles. Of their stop at Pitcairn Island, where the crew took on fresh supplies of oranges and bananas, she wrote to Jean: “In the light of the ship we could see pale white flying fish cruising about under the water, which was soon a rubbish dump of banana skins as the passengers gorged.”7

Juliet Peter Façades, W.9. 1954. Lithograph. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū

London was a world ripe with possibility for an artist with an eye for the poetry of everyday life: “The more one sees and does in London, the more is revealed, the more possibilities open up. Everybody eventually finds their own London, that aspect that most appeals to their interests.”8 Juliet explored it with her sketchbook in hand, capturing its people, architecture and atmosphere with characteristic economy and humour. She drew stone façades, ornate iron gates, a flower-seller and her cart, the Cockney men who gathered at Billingsgate fish market, a string of ponies for hire in Regent’s Park Zoo, a drooping line of coppiced trees along Clifton Road and, of course, the fashionable locals exercising their dachshunds and poodles. “It was natural for me to incorporate some of the local scene of Hyde Park. I admired the comings and goings and variety of what one saw ... I loved London, really.”9 Many of these scenes were translated into lithographs that were later exhibited in New Zealand, including at the annual Group exhibitions in Christchurch. At the time, Juliet and Roy were amongst the few New Zealanders working in the medium: “There weren’t many people doing printmaking then. We were pioneers, I think.”10 Purchasing an old London taxicab for £25 after it was advertised on a noticeboard at New Zealand House, the Cowans explored the Continent and also ventured into the English countryside, as Juliet’s later advice to Jean attests:

When you do set out to explore the by-ways of Britain, I do recommend that you go to Somerset. On both my trips, I liked it more than any other part I saw. To start with, there is Bath, Wells and Glastonbury. Then there are forgotten hamlets with names like music: Dinder, [Compton] Dundon, Muchelney, Montacute (the latter has a wonderful Elizabethan great house) and 18th century town-lets such as Somerton. Should you go to Glastonbury, there is a very fine youth hostel on Polden Hill in heavenly open country beyond a place called (probably by the Romans) Street. Thereabouts the roads still follow Roman roads that converged to the Fosse Way and Somerset people still talk of “Green Ways” in the woods.11

In that letter, written a decade after returning to New Zealand, there’s a more than a hint of nostalgia for the freedom and excitement of those years: “Looking back on our own two years in London, and I was there for a year in 1951 also, I am sure it was the happiest and certainly most stimulating time of my life.”12

United by a shared aversion to authority and conformity, Juliet and Roy resisted the stylistic shift sweeping through the art scenes of both London and Wellington.

We weren’t interested in abstraction. We solved that problem very early – we took up ceramics and nobody could tell us in ceramics what we ought to be doing. We had no intention of going abstract. It wasn’t our thing. … The pressure was on artists, and we refused to go with it. At that period, in the 1950s and 60s, everyone was going abstract on the local scene, and we went our own way. It was very simple.13

Juliet Peter London Pigeons 1954. Lithograph. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū

Juliet’s London works, however, are far from straightforward representation. Instead she applied an approach she had developed while at Canterbury College – to the frustration of more conventionally-minded lecturers like Cecil Kelly and Richard Wallwork, who would have preferred her to obediently copy what was in front of her:

I had other ideas, that I could use the subject but I wanted to do something else with it. I didn’t want to sit down and just copy a piece of landscape. We all wanted to get away from the photographic approach and bring in some personal input. We were getting away from the idea that you had to view landscape as if you were a camera. We were taking the elements and adjusting them towards an individual point of view.14

In works like October, London (c.1954), Juliet deftly manipulates scale, colour and form to intensify the autumnal atmosphere and create a sense of immediacy and immersion. Placing three large falling leaves immediately in our line of sight, she brings us right into the centre of the scene, experiencing it as much as observing it. And while she rebuffed the official movement, Juliet wasn’t above borrowing a few tools from the abstractionists’ repertoire, often simplifying forms and adapting them in ways that defy pure representation. In London Pigeons (1954), which incorporates the distinctive classical portico and spire of the Grosvenor Chapel in Mayfair, she draws the cluster of wide-eyed birds with loose, gestural outlines, the forms intersecting and overlapping to create a geometry of life and movement.

When the Cowans left London in 1955, their keepsakes were suitably idiosyncratic: a nineteenth-century lithographic press and a small electric kiln. These would be the bedrocks of the artistic partnership they would establish at their home in Heke Street in the bush-clad Wellington suburb of Ngaio. They worked there together for more than forty years, making a modest living from selling their works privately and relishing their independence. Though they contributed generously to New Zealand’s art scene by sharing their knowledge of pottery, kiln-making and cutting-edge colour lithographic techniques, they remained a society of two – an exclusive club defined by practicality, industry, invention and humour. Each year, they shunned the official Daylight Savings changeover, preferring to remain permanently on what they called “Summer Time”. As far as I know, they didn’t write a manifesto, but Juliet went some way towards suggesting one in an interview she gave late in life: “the arts”, she said “are deadly serious – and full of fun”.15

Juliet Peter October, London c.1954. Lithograph. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, donated from the Canterbury Public Library Collection 2001