Len Lye Blade 1959. Collection, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery/Len Lye Centre. Courtesy of the Len Lye Foundation

Len Lye Works

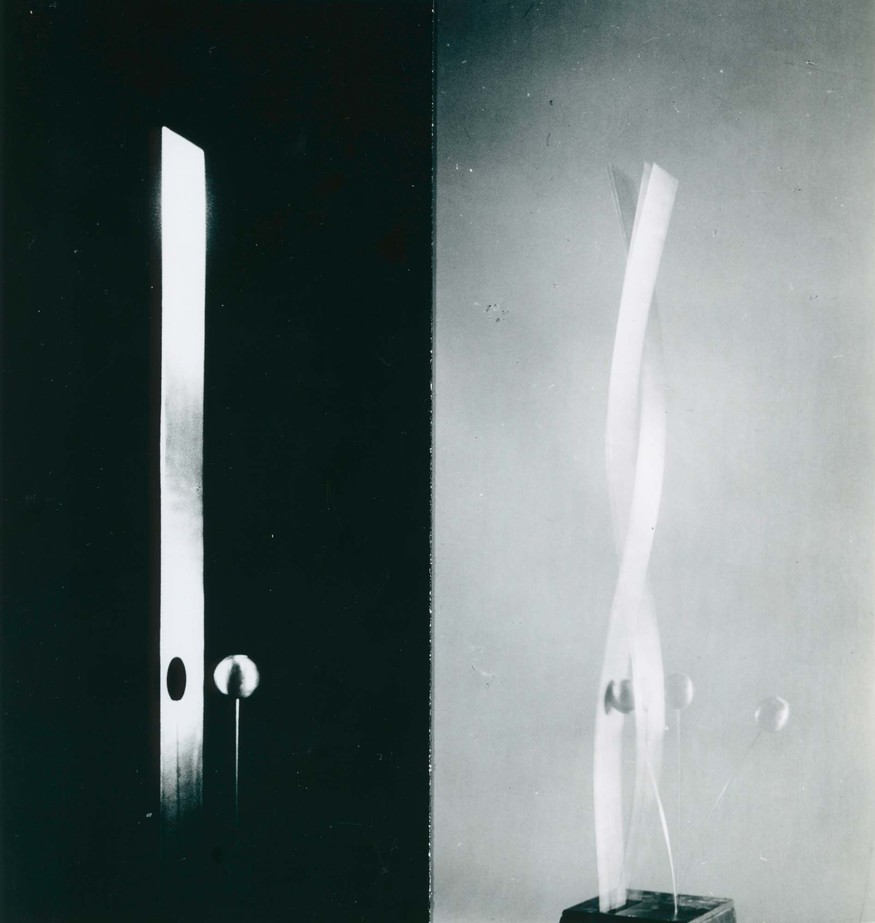

The glancing body of a hooked swordfish; the shivering skin of a panicky horse; a shiny tin kicked in rage by a young boy outside the Cape Campbell lighthouse. This triptych of memories was the inspiration for avant-garde New Zealand sculptor, painter and film-maker Len Lye’s Blade (1972–4) – a vertical band of steel that curves, flexes, arches then hammers frenetically against a cork ball in a fury of light, sound and movement.

‘I see the sculpture Blade as three evocative sensory moments of past experience which have sunk down into my thighs,’ he wrote. ‘[T]hat’s how Blade shines and quivers when it is doing its stuff – flashing light, shimmering fish and taut quivering horse.’1

In its frenzied motion and escalating action, the sexual connotations of Blade are unmistakeable, but there is also a kind of formality, an expression of rhythm, which the artist associated with dance and body movement, says Len Lye Foundation director Even Webb. ‘For me it is one of the works where we can see him courting with chaos. It is possible to make Blade so it is straight drumming, but when it is interrupted unexpectedly, when the blade starts driving the motor or the ball gets out of sync or something unpredictable happens in its performance – that is when it comes alive.’

Blade was first shown in this country forty years ago, in Lye’s inaugural New Zealand exhibition at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, where it was seen alongside the newly completed Fountain III and the alarmingly dynamic Trilogy (A Flip and Two Twisters). As a result of this exhibition, and the skill and enthusiasm of engineer John Matthews – since chair of the Len Lye Foundation – and other supporters and artists, Lye decided to leave his entire collection to the people of New Zealand, to be held at the Govett-Brewster.

As well as preserving and promoting the artist’s work and ideas, the Foundation was charged with fulfilling his plans for new, larger and louder versions of his existing ‘tangible motion sculptures’ – as seen in the forty-five-metre Wind Wand currently bending and glowing on New Plymouth’s foreshore. Lye also left the Foundation the task of realising new works that, because of lack of materials, expertise or money, he was unable to achieve before his death in 1980.

Len Lye Blade 1959. Collection, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery/Len Lye Centre. Courtesy of the Len Lye Foundation

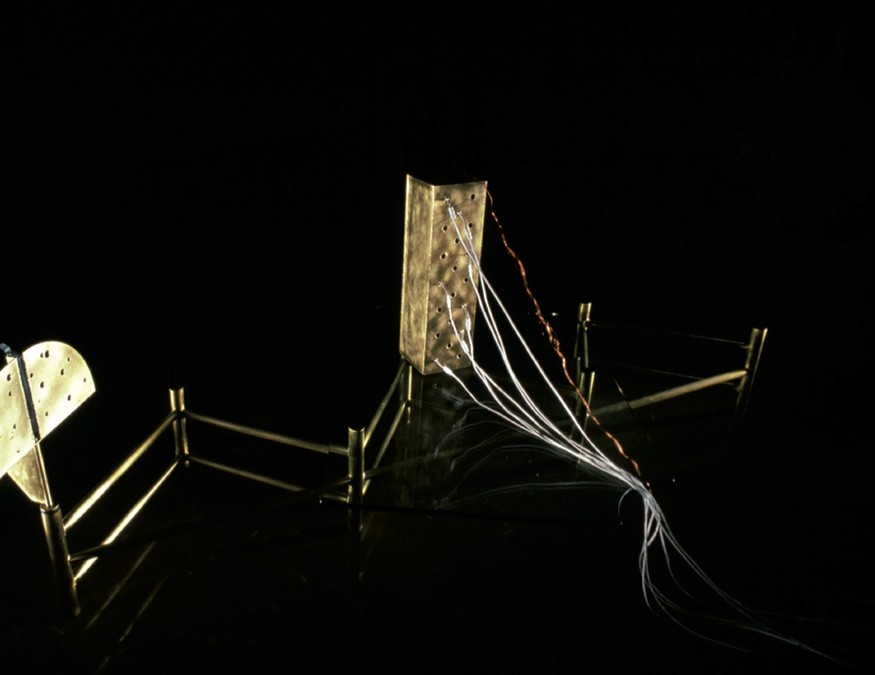

A twenty-five-year collaboration with the engineering department at the University of Canterbury has resulted in a list of at least ten new Len Lye projects. Research has already begun on a larger version of Rotating Harmonic, a simple rod that oscillates backwards and forwards to create a three-dimensional virtual volume in space; an enlarged version of Witch Dance, a circle of motorised, twelve-metre high, shimmying and shaking wind wands; and Snake God and Snake Goddess, a ten-metre long sculpture completed by former engineering student Alex O’Keefe featuring a large stainless steel strip that rucks and undulates before rearing into the air and shooting a bolt of lightning into a sun-like sphere.

Work is also underway on a massive ten-metre version of Blade. Shayne Gooch, head of mechanical engineering at the University of Canterbury, says it’s a project with its own sizeable challenges.

‘It isn’t simply a matter of getting the same material and making it ten times as big. But Len Lye knew this. He didn’t drive a car, but he had a very good feel for movement and metals and how they move – he knew that if you change the size of something it moves differently.’

Gooch quotes Lye’s analogy of a three-foot shrub falling in the forest, compared to the accelerating rush of a 100-foot redwood tree tumbling to the ground.

For his PhD in 1997 Gooch made a 3.3 metre version of Blade, over twice the size of Lye’s original work, which was shown in the Botanic Gardens as part of the Robert McDougall Art Gallery’s Sculpture in the Gardens exhibition. Where Lye relied on cold-rolled steel, commonly used in bandsaw blades, Gooch used a stronger, lighter and more resilient titanium alloy.

The new, even larger version will be constructed using the ‘largest piece of titanium alloy available on the planet’, sourced by Gooch from an aircraft manufacturer supplier in Shanghai, and a clamping device and variable stroke mechanism designed by engineering student Tim Spencer. The resulting movement is expected to be able to negotiate the required path between apparent unpredictability and regulated shape and movement.

‘When we first looked at the behaviour of Blade we didn’t think we would be able to model it because it looks chaotic at times,’ says Gooch. ‘Lye liked aspects of unpredictability but what we found with the different mode shapes – if you are vibrating at one mode there are elements of other modes. So you end up with a shape that looks chaotic but is actually something you can calculate.’

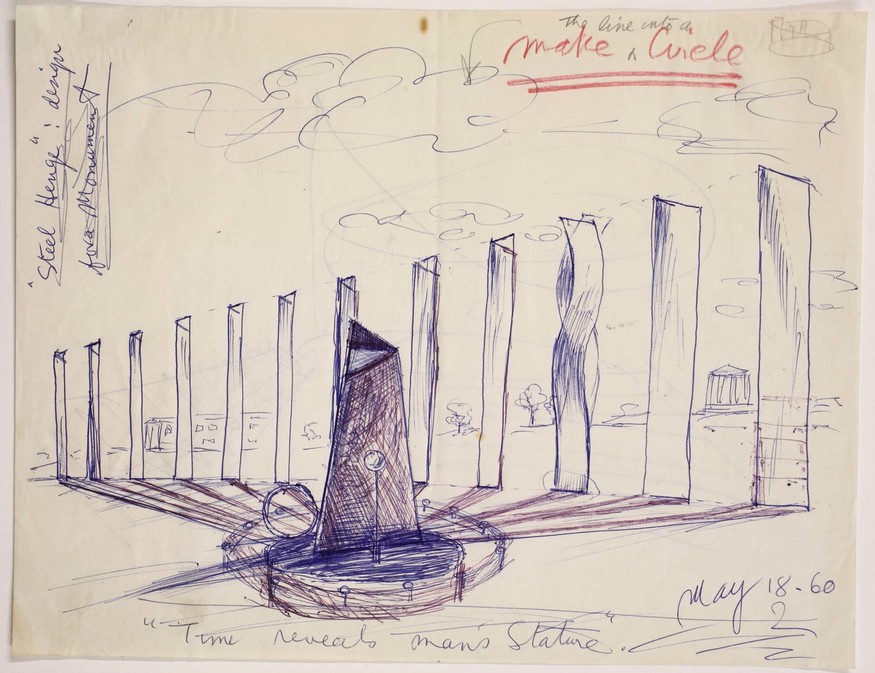

Mastering the design for the ten-metre version of Blade will be an essential first step to fulfilling Lye’s dream for Steel Henge (or Timehenge): a series of twelve different sized blades, of which this will be the largest, arranged in a circle like numbers on the face of a clock and reflecting light, as Lye posited, ‘like an Aztec monument to the sun’.

Len Lye Sketch of ‘Steel Henge’ 1960. Collection, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery/Len Lye Centre. Courtesy of the Len Lye Foundation

But, as with so many of Len Lye’s works, the seemingly chaotic yet predictable movements of such monuments rely on a level of flexibility and vibration at odds with standard engineering practice.

‘Engineers are taught to steer clear of vibration,’ says Webb. ‘A vibrating propeller shaft in a ship or a wheel bearing in a car is antithetical to good engineering design. Similarly, architectural designs are aimed at minimal structural flexibility.’

In the University of Canterbury’s engineering department, students involved in Len Lye projects are learning to predict exactly what happens when you do get vibration in machines.

‘Normally you would avoid it but making something that shows vibration is good from an educational perspective,’ says Gooch. ‘It is basically Newton’s law – force equals mass times acceleration – then you can work out how something moves and with a flexible movement like Blade you can predict what shape it will go into.’

The realisation and serialisation of Lye’s sculptural work has been made possible by the advent of new materials and technologies. But again, the challenges are immense. Too much control and the works tend to lose their shining sense of chaotic unpredictability. Too little and the machinery can fail, movement can go awry. With some works, such as Trilogy, Lye pushed the control mechanism to the edge of its capacity, until the motion itself was driving the machinery – what Webb calls ‘the tail wagging the dog’.

Duplicating this movement, often the result of antiquated control mechanisms, requires a clear understanding of what the artist intended.

‘Lye was over-driving his original motors so they were doing something that was imperfect but that was inherent in the art work,’ says the Govett-Brewster’s Len Lye curator Paul Brobbel. ‘So how do you replicate something that is perhaps not well designed in an engineering sense but well executed in an art sense?’

Len Lye Blade 1959–76. Courtesy the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery/Len Lye Centre

To ensure the movement remains paramount, the Foundation tries to limit any sound that would distract from the overall quality of the performance of reconstructed works, often replacing old analogue motors made by Lye or his colleagues, who were not necessarily engineers, with digital systems.

Did the sound of the old machines driving his work bother Lye? We don’t know, says Brobbel, ‘but he saw the motors and the bases as subordinate to the figure of motion. The question is whether you go back to replicating exactly the original materials or is there any leeway to achieve the same work or the same experience using the benefits of modern science and technology?’

The challenge, says Brobbel, is to work out what the machinery he used was meant to do and what he did to it that perhaps wasn’t perfect, ‘and how we simulate that with the exact motion but with a purer experience.’

The posthumous realisation of such ambitions – indeed the posthumous realisation of any artist’s work – comes with its own set of ethical considerations. Is it right to give form to an artist’s unrealised idea? Or to make copies of existing works without the final approval of the artist? If new sites are selected, new materials used, different scales designed and a ‘purer experience’ defined and developed, are we not imposing a different aesthetic on the final object?

‘We’ve been challenged on this for many years and I think it is a worthwhile challenge,’ says Webb. ‘The simple truth is we don’t know what Len would want if he was around today. Artists do change their minds – we all change our minds – but Len did see the possibilities in technologies that weren’t available to him then.’

Although lacking the certainty of Lye’s final approval, for each new work the Foundation undertakes thorough research, drawing on Lye’s notes, sketches, even audio and video recordings, and enlisting a robust auditing process. ‘The trustees bring all their knowledge to bear on it, including their understanding of Len’s intentions and other works it might be similar to,’ says Webb. ‘And Len gave the Foundation authority to do this.’

Back at the University of Canterbury, work is continuing on Lye’s rugby-pitch sized Sun, Land and Sea, for which Snake God and the Snake Goddess is a smaller prototype. The idea behind the work is archaic – a creation myth retold in new technologies, engineering perspicacity, and the volatile movement of pulsating strips of highly polished steel representing seven sea serpents, a cave goddess and a sun god. It is also the sort of vision that ensures Len Lye a unique yet persistent place in the story of avant-garde twentieth-century art.

‘Len Lye is an exciting proposition to a lot of people around the world,’ says Brobbel. ‘As a fringe figure he is always kind of cool, he is always attractive, and there will always be a new generation discovering him and thinking they are on to this guy who hasn’t had his dues. And Christchurch has a stake in Len Lye – he was born there and now the engineering happens there. It is nice to recognise the relationship.’