Jin Shan detail of Self-Doubt 2014. Plastic. Photo: Sophie McKinnon from a studio visit in Shanghai

Dancing on shifting ground

Sophie McKinnon explores art, resilience, change and urban regeneration in China.

In the winter of 2006 I found myself traipsing around the 798 art district in Beijing, in search of someone to talk to about factories morphing into gallery spaces. I was fascinated by the story of a defunct industrial district turned rapidly expanding contemporary art zone. 798 had been the unofficial site of regeneration for Beijing’s art community since 2001. This community had spent over two deca+des plagued by isolation and displacement but seemed finally to be finding a home.

Arrow Factory. Photo: Sophie McKinnon

I distinctly recall sitting in a deserted pizza shop whose paint was fresh and heating broken, listening to an artist describe how challenges and obstacles are the greatest asset to positive change. ‘Without limitations, anything is possible,’ he said. ‘If someone builds a wall, you work harder to find a way over, through, or around it.’

Nearly ten years later, the district has evolved considerably. The twelve or so galleries have multiplied to over 200, and have been joined by design stores, restaurants, photo studios, and even a cafe serving a ‘New Zealand style flat white’ for a frustratingly artisanal $9. One or two artists’ studios still remain, but most have moved on due to rising rent. This is a classic art district paradigm—in with gentrification and out with artists. But the commercialization of the area signaled an even more interesting phase for Beijing’s art community, one which is robust, responsive and increasingly varied geographically.

In 2008, while Beijing hosted the Olympic Games and prepared to show the world its glistening new sports stadiums and meticulously engineered blue skies, artists Rania Ho and Wang Wei were adjusting to new opportunities on a smaller scale. The Arrow Factory, a glass door art space occupying 12 square meters on the site of a former vegetable shop in one of Beijing’s oldest hutongs (alleyways), was one of the first independently run project spaces outside 798. What began as a conversation among friends about the impenetrability of 798’s mass crowds and macro gallery formula has now become a mainstay of a new generation of organic, grassroots art spaces. Exhibitions at Arrow Factory are visible from the street, but ask nothing of the audience. There are no opening hours, no entrance tickets, and there is no doorway in.

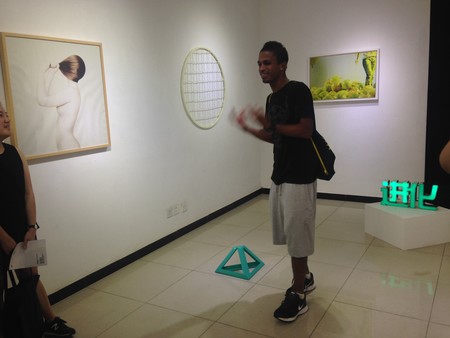

Installation view Intelligentsia Space Beijing, with founder and curator Cruz Garcia Frankowski. Photo: Sophie McKinnon

In 2014 Cruz Garcia Frankowski founded Intelligentsia Space, also in the hutongs, as a way to serve an artist community chasing opportunity. Frankowski says: ‘We don’t romanticize our location because we want people to understand that what we are doing is independent of that’. Spaces like this are alternative in the sense that they offer up new approaches to what art spaces can and should be, in a place evolving as fast as it is questioning that evolution.

The contemporary art community in China is associated with resilience amidst social turmoil, political pressure and shifting urban circumstances. Yet adjusting to change is nothing new. This attitude is pervasive throughout Chinese society. Groups of elderly dancers gather in local parks to exercise to music. It’s a community activity, rigorous in its regularity. If the space they use becomes a construction site, they move to a public square, or a street corner. If it becomes a modern mall, they continue at the foot of the mall, reclaiming the space in collaboration with change.

Similarly, the traditional image of the brooding artist in a bare bones loft as a victim of change has given way to one of the artist as savvy entrepreneur, moving fluidly between the studio and the market while continually reinventing. Shanghai-based artists Jin Shan and Maya Kramer relocated by invitation from a studio near downtown, to the outskirts of the city. They tell me: ‘It was an opportunity too good to turn down—our landlord loves art. He offered us the space at no cost, in exchange for some pieces for his collection. We leapt at the opportunity’. Such aggressive commercial/residential trade-off for artworks could be construed as crude, but it is all a matter of perception. This pragmatism has come to be one of the defining qualities of artists’ response to change in China today. Jin and Kramer are now in a new mixed use complex far from any foot traffic. Yet on the day we visited, Jin was busy receiving a queue of museum and gallery representatives who had traveled to see his work.

Zheng Bo Garden (Lane 62 Zhaojiabang Road) 2015. Installation from Weed Party at Leo Zu Projects. Photo: Sophie McKinnon

Installation view of Ai Weiwei Bicycle basket with flowers 2014. Porcelain. Chambers Fine Art, Beijing. Photo: Sophie McKinnon

Just up the road is Xu Zhen, an artist whose name and brand, Xu Zhen produced by MadeIn Company, are one and the same. MadeIn is a self-described artist organization which operates as, and riffs on, art-world institutional structures—the artist, the gallery, the archive, the fabricator, the agent, and the curator, among others. The name MadeIn refers to the abundance of mass produced items made in China and the psychology of China as the factory of the world. Zhen’s installation series Eternity-Winged Victory of Samothrace, Tianlongshan Grottoes Bodhisattva (2014) fused classical Greek and Buddhist marble sculptures into hybrid, top-heavy columns. The series is full of irony but speaks of a deeper reality, one which champions infinite combinations of ideas rather than the immovability of institutions.

Zheng Bo’s 2015 installation Weed Party at Leo Xu Projects in Shanghai painstakingly re-created a derelict industrial façade in the gallery - from greasy tiles, graffiti, and litter—including local weeds at the base, climbing to a grass arboretum on the top floor. Xu explains that these grasses were introduced, largely from Europe and North America, and survive extremity while continuing to flourish. They aren’t pests—they are a socio-political metaphor for adaptation and resilience.

It’s tempting to think of regeneration as a process of complete transformation or the old adage of the phoenix rising new from the ashes. In China it is rather a matter of persistence. Ai Weiwei placed fresh flowers in the basket of his bicycle every day until he received his passport back. Now enshrined in porcelain, the flowers continue to say, ‘I’m still here’.

Sophie McKinnon has worked with the Red Gate Gallery, the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing, and as a programme developer for Arts Can Do, an art based education project for disadvantaged children in urban and rural China. She coordinated the 2014 China-based Festival of New Zealand Filmmaking and runs China Contemporary Art & Architecture Tours with co-founder John O’Loghlen.

Installation view of Zheng Bo Weed Party at Leo Zu Projects. Photo: Sophie McKinnon