Transformers

Curator Ken Hall writes about his experience of working with artists Chris Heaphy and Sara Hughes, as part of a small team with other city council staff and Ngāi Tahu arts advisors, on the Transitional Cathedral Square artist project.

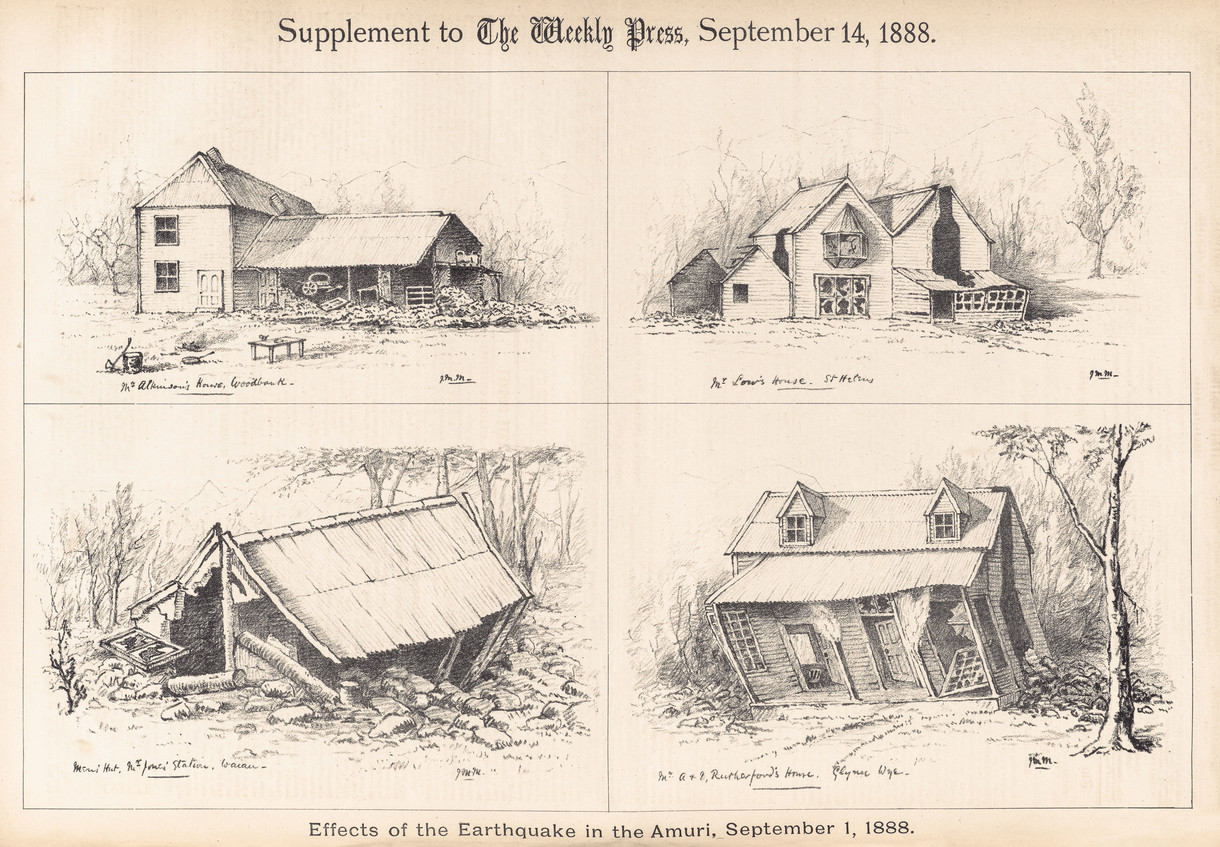

For twenty-eight months following the 22 February 2011 earthquake, Christchurch's Cathedral Square was part of a vast, army-controlled no-go zone. Procuring permission to enter was a task, and once inside it felt shockingly post-apocalyptic – abandoned, grey and dead. Heavy machinery and hard-hats came and went – contractors, visiting celebrities and politicians, the occasional TV crew – but its reopening was attached to bureaucratic wrangling and uncertainty. Meanwhile, behind the fences, the familiar historical heart of the city was largely reduced to landfill; in the name of recovery, mountains of rubble were trucked away.

Recognition of the cultural significance of this public space needs no particular explanation. From the highest levels in the city council, it was obvious that if people were to regain access to the Square, it had to be welcoming and influence beyond stolid pragmatism must be allowed to exist. Of course, its eventual reopening on 6 July 2013 was only possible once public safety issues had been properly addressed, with the installation of barriers and fencing to limit risk during ongoing deconstruction and repairs. But early plans for reopening also included seating, planting and attractive hoardings; it was soon recognised that these could be more than decoration. At this point, a small team consisting of relevant council staff and Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu arts advisors was formed, and two artists were invited to become involved.

Auckland-based Chris Heaphy and Sara Hughes – both artists of calibre and outward-looking character – agreed to enter the project, to which they brought complete commitment and consummate results.

For Heaphy, his ancestral Ngāi Tahu links were valuable in relation to the reviving and ongoing reinterpretation of this space. As a painter Heaphy characteristically reworks emblematic forms to achieve a dazzling, multi-layered storytelling; a rich exploration of shared histories and the sometimes problematic push-pull of cultural identity. That his exploration is open-ended rather than neatly stitched up or exclusive also fitted well with what was clearly a critical moment in the life of this significant public space.

Sara Hughes is also an artist who regularly connects with the history of the spaces in which she works. Her personal history with this city includes United We Fall (2008), a temporary installation at the Gallery that clearly attested to her ability with large-scale projects. In first surveying the abandoned Square in November 2012, both artists responded with a desire to bring something opposite to what they were experiencing: they saw a need for vivid colour as well as a sense of order, energy and life.

Chris Heaphy was keenly attuned to the near invisibility of Ngāi Tahu (or any Māori presence) in the Square, apart from a small engraved memorial by the edge of the more generous 'First Four Ships' plot. He was likewise drawn to the cathedral in its present state as something central and inescapable – a fact that needed comprehending. Heaphy's Planted Whare is a cleverly participatory architectural form that allows viewing of the cathedral through an open wire-fencing end – a reasonable break in the (mostly continuous) wall. Constructed of robust steel scaffolding and covered with plastic bread baskets filled with a profusion of plants, the house also matches one of his earliest intentions – to see a colour field of flowers before the broken cathedral. While speaking of the beauty and fragility of life, these also held for him an understated memorial role; as an affirmation of life and existence, the planted house is a hopeful presence alongside acknowledgement of loss. Facing the cathedral, positioned absolutely centrally within the Square, it makes gentle conversation with the historical British architectural form, honours Māori presence within a broad symbolic timeline and also represents a meeting place – an inclusive, encompassing welcome to all.

Extending far beyond the sides of the whare, Heaphy's elaborate, intensely coloured hoarding panels are digitally designed and printed. Existing as a vast and lively backdrop to a wide variety of human activity within the Square, the boldest forms within the schema immediately invite the eye to move around, dancing between them and various architectural elements on the cathedral. From a distance, the predominantly circular shapes explode like cactus flowers or fireworks, unfolding brilliantly across an expanse of black. Some are reminiscent of stained glass windows. The effect is intricate as well as powerfully bold, with reward to be gained by zooming in to comprehend the generous unfolding of symbols and elements distinctive to Heaphy's painting practice. These include axes, pipes, top hats, weapons and walking sticks; legs, boots, torsos, tongues and hands; profile heads and grimacing tiki; playing-card hearts, clubs and diamonds; tuning forks and triangles; and recent additions – geometric Gothic-inspired architectural motifs. Objects are formed into astonishing kaleidoscopic configurations, sometimes into vast butterflies. Heaphy's visual lexicon also includes hilarious stick figure angels; colonial gents; and Māori men with topknots, after Louis Auguste de Sainson – a French artist who visited this region with Dumont d'Urville in 1827. Numerous birds may also be found, including kōtare (kingfisher), kāhu (harrier hawk), ruru (morepork) and koreke (the extinct New Zealand quail). This last makes reference to a 1903 Lyttelton Times account of an old timer recalling having shot some 120 koreke on a single day within the boundaries of the early Cathedral Square.

Sara Hughes Flag Wall 2014. Mixed media

Heaphy and Hughes both responded to the physical, symbolic and historic aspects of the space, working out the territorial nature of the project with cordiality. Hughes's contribution has been installed in two stages, each making use of existing structural elements – either temporary or fixed – in the Square. The first of these was (the now ever-present) safety fencing. Both artists designed dynamic visual schemes to be printed on durable cloth to wrap hurricane fencing on building and demolition sites. Maintaining a bold palette, Hughes transformed two further groups of fences with elaborate patterned designs. Adapting a commercially available product – plastic 'put-in cups' made in the USA for emblazoning team logos on hurricane fencing in sports arenas – she took these in a very different direction. Individual cups are carefully pushed into place, overlapping and interlocking at the edges, creating an effect like pixels on a digital screen or individual cells on an embroidery pattern. Indeed, one of the sources used by Hughes was a collection of historical stitching designs from the James Johnstone Collection in the University of Canterbury's Macmillan Brown Library. Johnstone was for many years a teacher at the Canterbury College School of Art; embroidery designs by students who were there from the 1930s to 1950s are part of the collection that Hughes surveyed.

Creating a vivid welcome at the south entrance to Cathedral Square, a set of fence designs based on simplified flower patterns are particularly reminiscent of embroidery. They also return to miniature scale when viewed from a distance, elegantly asserting the persistent value of creative labour, as well as of colour, pattern and order. Further groups of Hughes's patterned fences, with openings solidly filled to create a more tartan-like appearance, are positioned in other locations in the central Square and create an unexpected sense of psychological anchoring through their bold colour.

Hughes's Flag Wall has been just recently completed, and as a temporary installation will stay in place for at least six months – longer if the flags can last. Working with four empty flagpoles in front of the old central Post Office building on the south-west corner, Hughes has created a vivid wall of movement that provides a dynamic, uplifting presence to this space. For Hughes, it was important to 'bring colour and energy into the Square as a way to welcome people back'. Her ongoing investigation into the emotional and psychological effects of colour joined here to her recognition that a giant wall of flags could convey 'a spectrum of meaning, encompassing the political and the celebratory'. The 648 flags laid out in carefully ordered rows are abandoned to movement in the prevailing wind, seldom hanging still, so the overall scheme of the Flag Wall is not necessarily picked up at once by the eye. When the fluttering is frozen through photography, however, the installation immediately reveals its layered diamond pattern, one that is also strongly linked to those on the solid-fill hurricane fencing. A similar pattern appears elsewhere in the Square in slate 38 tiles, eastwards on the cathedral roof, and in artwork that is no longer seen: tukutuku panels by Ngāi Tahu weavers in the cathedral interior.

When walking around the Square now, it is interesting to try and imagine the space without the work that these artists have created – take it away and it remains a thoroughly difficult space. This temporary work is far more than sticking plaster or wallpaper, however, and argues centrally for many extremely valuable qualities that this city sorely needs. This includes recognition of the value of the stories of this place, many of which are preserved in elements of historical architecture that (possibly barely) remain. It also places a high public, civic and cultural value on the realm of the imagination – the place where art is allowed within a culture to speak and breathe. Planners, architects and developers in this city would do well to engage artists of proven calibre at a real and genuine level, opening up different kinds of conversations, initiating innovative partnerships and finding new ways of generating exciting and well-considered, high quality ideas.

Ken Hall

Curator