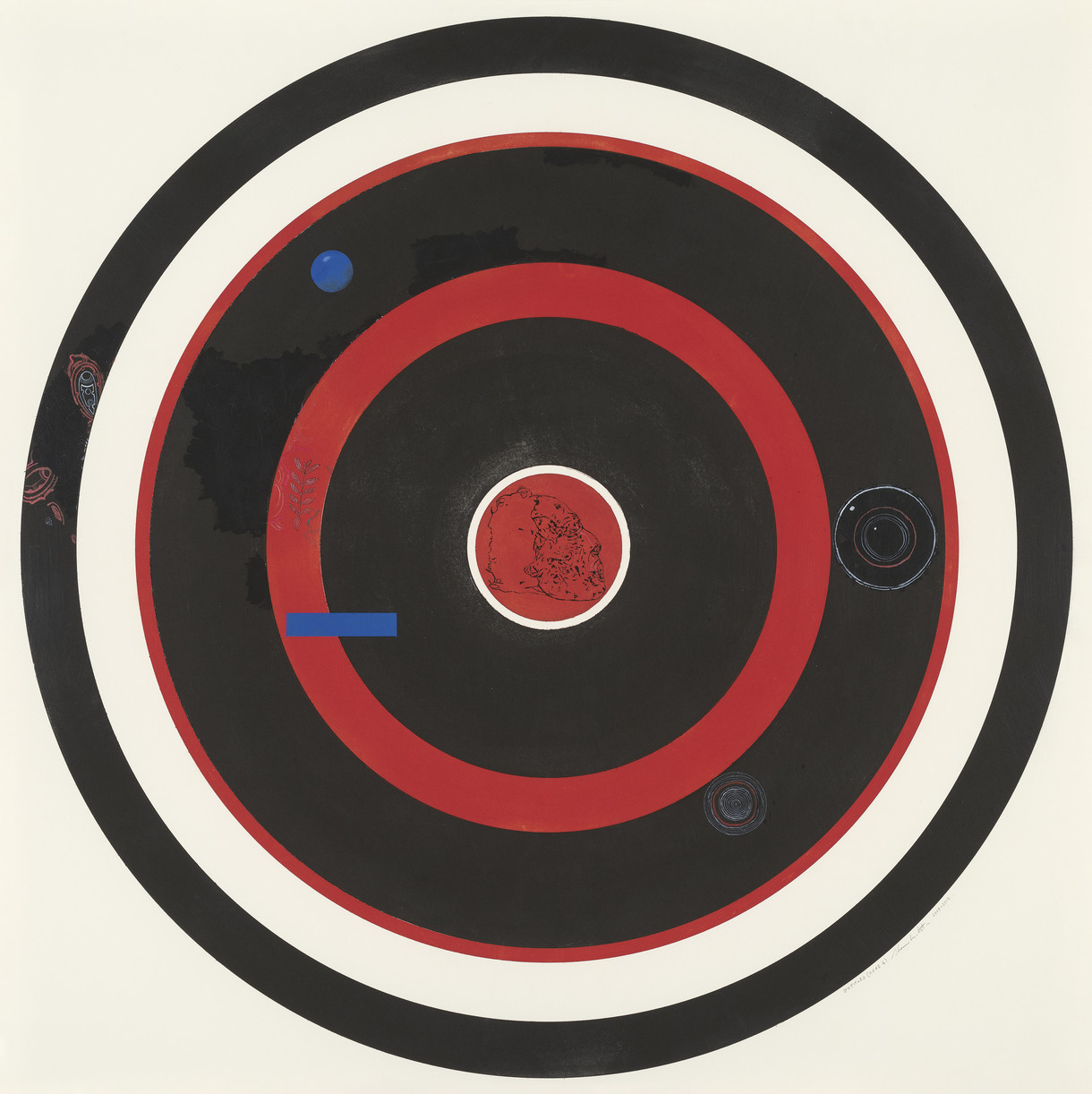

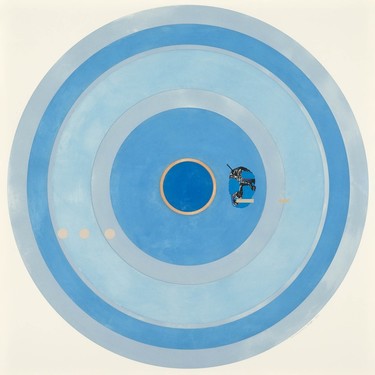

Shane Cotton Untitled (Head 1) 2009–12. Acrylic, photo-etching and aquatint on

paper, produced at The Gottesman Etching Center, Kibbutz Cabri, Israel, 1/1. Private collection

Speaking sticks and moving targets

New works by Shane Cotton

The Hanging Sky brings together Shane Cotton's skyscapes from the past five years. But the core of the exhibition is a big group of freshly made works of art. Senior curator Justin Paton first saw them in completed form during the show's installation in Brisbane. Here he describes his encounters with a body of work 'at once beautiful, aggressive, protective and evasive.'

It's day two of the Shane Cotton install at the Institute of Modern Art in Brisbane, and all through the day big paintings by Cotton have been emerging from their crates and finding their places around the walls. There in the first room is Christchurch Art Gallery's Takarangi, with its birds whooshing out into deep space, then the brooding The Hanging Sky next door and The Painted Bird in the room after that—paintings from different moments that are coming together in one gallery for the first time here. After months of rearranging tiny paper versions of the paintings inside a 1:25 scale gallery model, this is the moment I always look forward to—when the real things arrive in the room, assert themselves physically and start making demands of their own.

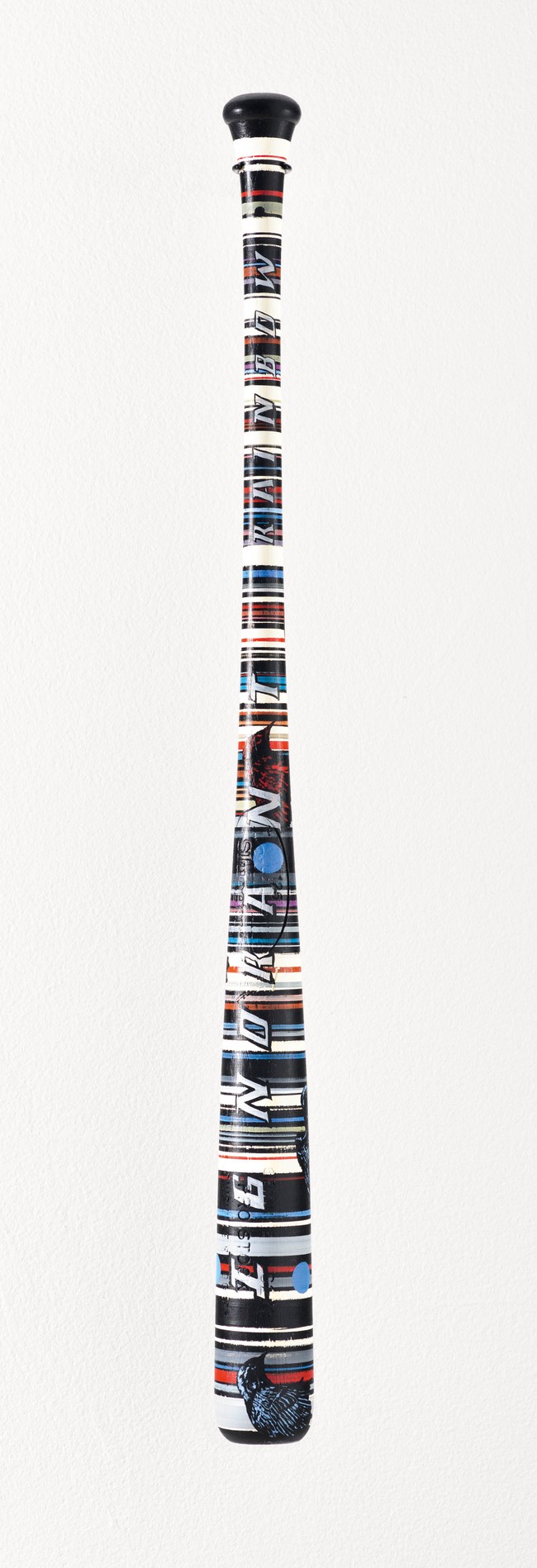

What's distracting me at the moment, however, is a table in the quietest gallery, where the conservator, Rebecca, is slowly unpacking a box literally full of surprises: ten painted baseball bats that Cotton completed in New Zealand only days ago. One by one they're withdrawn from their sleeves and laid out for inspection and cataloguing: the Hit Marker, the Myth Smasher, and the Paradise Club. Cotton, it ought to be noted here, is a card-carrying baseball fan, with a painter's special affection for the geometry and visual trappings of the game. And he's clearly had a lot of fun devising a livery or look for each bat. With their airbrushed titles and custom paint-jobs, they look a little like high-end collectibles—the kind of muscled-up artefacts that a baseball obsessive might display in a cabinet in their lounge. But a longer inspection discloses details that push these objects somewhere far beyond fandom. Tipping a bat in her gloved hand and running a torch down its surface, Rebecca illuminates skulls, strange rocks, tattooed Māori heads (of which more later) and the name of a renowned Ngā Puhi chief. Strangest of all, when you've just walked past Cotton's big skyscapes, are the painted birds stretched along the bats—as though someone has reached into Cotton's paintings and begun swiping birds from the skies. The results may be gorgeous, but you have to wonder: whose side are these objects on?

Shane Cotton Paradise Club (detail) 2012. Acrylic on white ash. Private collection

Cotton is by no means the only contemporary artist to conflate sporting conflicts with broader cultural ones. He's one of a number who like to tamper creatively with stuff lifted from the sports store or Physical Education shed. In a world where marketeers seek to ramp up our enthusiasm for sports teams by likening them to warrior tribes, these artists trick out mass-produced sports gear with uncomfortable reminders of real-world struggles. Local artist Wayne Youle has also done baseball bats in works like The Old Man's Walking Stick (2006), which evokes the clubs used by gangland leaders as well as the tokotoko used to arresting effect during oratory by senior Māori men. Rangituhia Hollis and Vaimaila Urale recently incised pool cues with Pacific patterns that made them look like sharp-tipped weapons (Mata Mata, 2012). And Francis Upritchard has given several kinds of sports gear memorably funny and feeble 'tribal art' makeovers, turning eight hockey sticks, for instance, into ceremonial staffs or spirit sticks (Jealous Saboteurs, 2005). In their different ways all these artists have their say in a long-running New Zealand debate about culture, property and power—a debate that has simmered or boiled through the last twenty years and shows no signs of cooling. What should a traditional object look like? Who has the right to make one? Who has the right to tell others they can't? And are these questions of life-and-death significance, or is it all just a game?

In 2011, the same year that Cotton painted his first baseball bats, the Waitangi Tribunal released its long-anticipated report on Wai 262, the complicated claim designed to protect Māori artistic and cultural works against 'offensive or derogatory uses'. Faced with the bizarre spectacle of Italian actresses performing a garbled haka in a 2006 television advertisement for the car manufacturer Fiat, it's not hard to see why Māori might want to protect precious songs, stories and visual forms from commercialisation without consent. But this kind of cultural protectionism meshes imperfectly, to say the least, with the practices of contemporary art, where artists frequently push and probe towards the edge of what's considered acceptable. And it is this uncertain edge—this foul zone—where Cotton makes himself at home with the bats. Serpent Garden, for instance, despite being a bat, is a remarkably traditional-looking Māori artwork, webbed in white lines that mimic the play of light along the surface of a carved weapon; it's no great stretch to imagine this object in a museum case alongside some spot-lit ancient patu or taiaha. But the same can't be said for the harshly named Coloured Head Crusher, which seems to wear, along its multicoloured length, the mortal emblems of past 'hits' or 'strikes'—Cotton's version, perhaps, of the bat wielded by the Nazi-killing 'Bear Jew' Donny Donowitz in Quentin Tarantino's lurid war film Inglourious Basterds. Far from being content to sit quietly in a museum case, this is an object that seems to want to stir up trouble—to knock out the glass that keeps history at a distance and release all its conflicts and contradictions.

Shane Cotton I Die, I Do Not Die (detail) 2012. Acrylic on white ash. Private collection

It is this live quality, above all, that makes the baseball bat paintings feel like something new for Cotton. Seeing them later that day in their proper positions, suspended by the handles in one long row, I couldn't help but respond to their decorative richness—particularly the pin-fine rings of colour that Cotton applies while turning the bats in a lathe. But alongside the richness there remains the suggestion that these objects have a purpose; that they are made, not to be appreciated at a distance, but picked up and somehow put to use. Naturally, we museum professionals would prefer it if you didn't touch, but the desire to grasp these artworks—to hold and heft them—is central to their effect. And it's surprising what happens to both the bat and its wielder when someone does pick one up. Suddenly that person has the floor; when they speak, you listen. I'm reminded here of things I've heard about Native American 'talking sticks', objects that have to be held by someone before they assume their full power. More than ever in Cotton's art, he seems to be inviting that kind of imagined participation, putting responsibility for how these uneasy objects are used emphatically in our hands. Imagine the guards aren't looking and you lift one from its hanger. Now what are you going to say?

Shane Cotton Ignorant Rainbow 2012. Acrylic on white ash. Private collection

This crackle of uncertainty also flows through Cotton's second large group of new works, the series of untitled prints (photo-etchings plus aquatint) that he made in 2009 during a two-week stint at the Gottesman Etching Center in Israel. The prints all feature concentric circles, a classic motif of modern art, and when I first glimpsed them, pinned to the far wall of Cotton's big studio, comparisons jumped immediately to mind: Kenneth Noland's swirling circles, Jasper Johns's targets, and Julian Dashper's drum-skin abstracts (one of which hangs in Cotton's home). Where Cotton's prints declared their difference was in the distinctive softness of their colour, a granular, time-and-weatherworn quality that was only apparent when one got close to the paper. There were overcast greys, sun-faded reds, pale yellows suggesting sand or clay. My favourite encounter during this viewing was with the work now called Untitled (Head 1), where a thin ring of yellow affects the blueness all around it like a chime very lightly struck. Little wonder that Cotton was taking his time before making painted marks on these surfaces. As well as being beautiful, each print was unique; there was no going back in the event of a mistake.

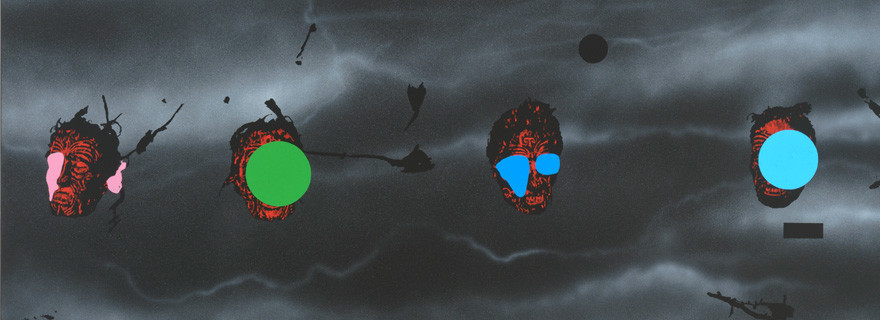

Three years later, here at the Institute of Modern Art, all that chromatic subtlety is still present. But it's been interrupted—at once heightened and troubled—by some painted embellishments. Working very sparingly in thinned acrylic over the aquatint inks, Cotton has populated each of his pristine abstracts with a vivid human fragment—one of the severed and tattooed Māori heads, known today as toi moko, that have been present in Cotton's paintings for a decade. With their extraordinarily tangled back-stories (first chiefly treasures and power objects, later grisly currency in the curio trade), these heads are some of the most volatile cultural images that an artist can reach for in New Zealand. And their first appearances in Cotton's paintings in the mid-2000s had the shocking force of a haunting, the faces looming out of blue-black nightscapes like zombie survivors of history—teeth bared, hair blown back, tattoos aglow in their faces. At first sight the new heads don't have that kind of urgency, because Cotton has partially blocked our view of each one with a bar or blot of paint. But the cumulative effect of the works is, if anything, more ominous. Placed inside cool white frames and arrayed regimentally on the wall, what the painted prints suggest irresistibly is a shooting range and its targets. Suddenly we're looking, not at meditative abstracts, but at icons of aggression. And suddenly the act of looking is charged with sinister implications. Those dots and strips of colour may be formalist devices, the kind of thing commonly used by abstract painters to 'tune' a larger field of paint. But they also evoke the terrible abstraction of a telescopic rifle sight: the fine tweaking of crosshairs and range-finding dots as the hunter takes aim at a distant target.

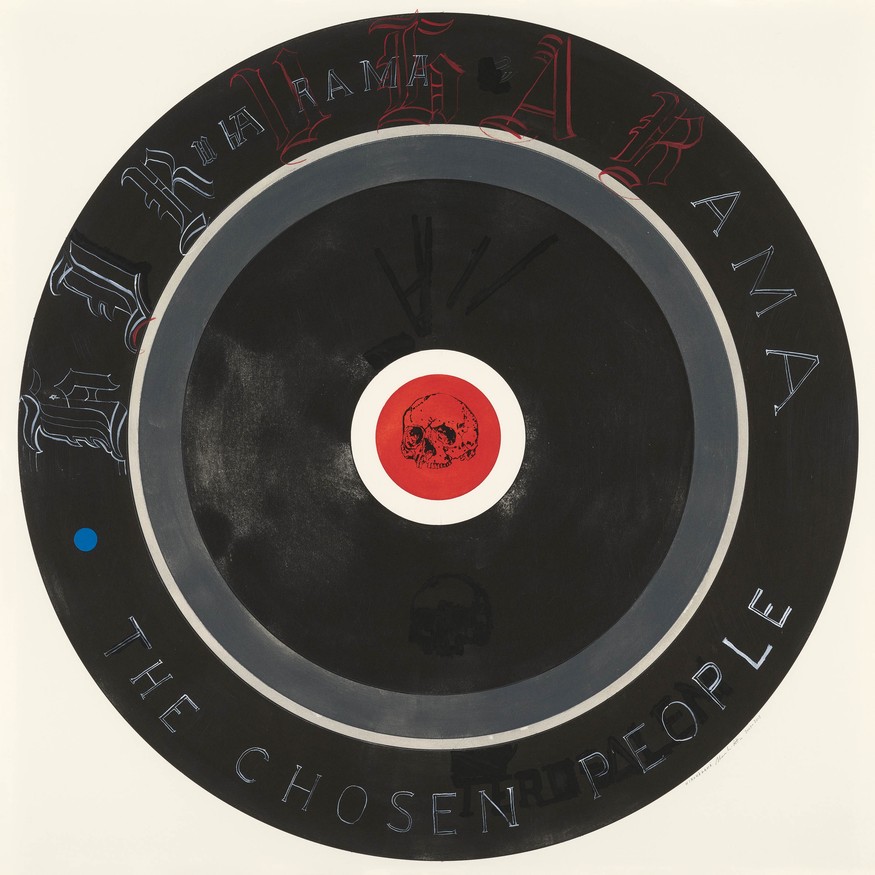

The longer you contemplate these cool and judicious images, the more heated and unstable they seem. Everything in them is carefully calibrated to scramble a clear sense of visual allegiance. It occurs to me, as it has to many observers, that the targets also resemble airforce roundels—the coloured abstract circles containing national symbols that are painted on the side of fighter planes, so that gun-crews on the same 'team' refrain from shooting them down (New Zealand's roundel features a kiwi, for instance, while Australia's features a kangaroo). But what does it mean to emblazon a roundel with a severed head rather than the national animal? Is Cotton proposing that the heads should serve as new national identifiers—true symbols of New Zealand history at its most bitter and tangled? And what, moreover, are we to make of the discovery that the colours in the background are not neutral at all, having been extracted by Cotton from the Israeli, Palestinian and Māori flags and the local landscape? Is mingling those colours the artist's way of noting the bizarre arbitrariness of national boundaries? Or is he rather creating a series of protective roundels for history's many forgotten faces—the Māori heads with their abstract 'blindfolds' now standing in for a larger category of victims? Do those victims all belong, as the gang-patch work Hiruhārama seems to be suggesting, to a gang sardonically called 'The Chosen People'? Or alternatively might Cotton be suggesting that these questions are all a bit too serious, given that whoever is taking aim at these targets appears to be using a paintgun rather than a real one? What we have here, I contend, are political artworks, but of an unusually muted and elusive kind. Political not because they declare one position but because they occupy several positions simultaneously. At once beautiful, aggressive, protective and evasive, they are indeed moving targets.

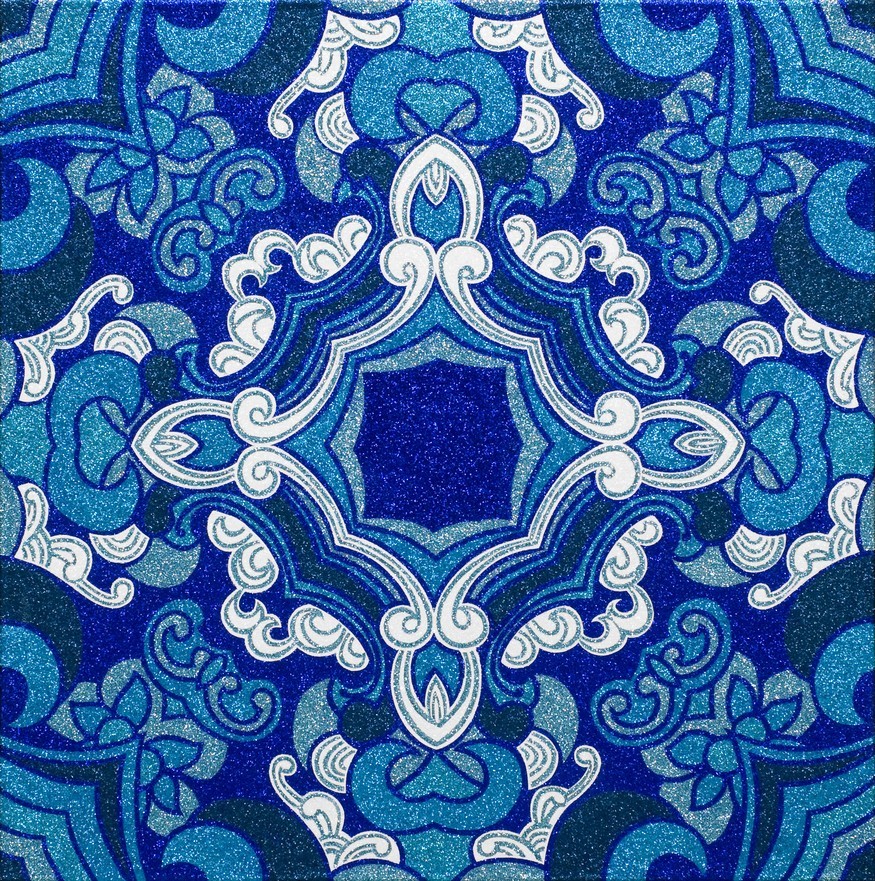

Shane Cotton Hiruhārama 2009–12. Acrylic, photo-etching and aquatint on paper, produced at The Gottesman Etching Center, Kibbutz Cabri, Israel, 1/1. Private collection

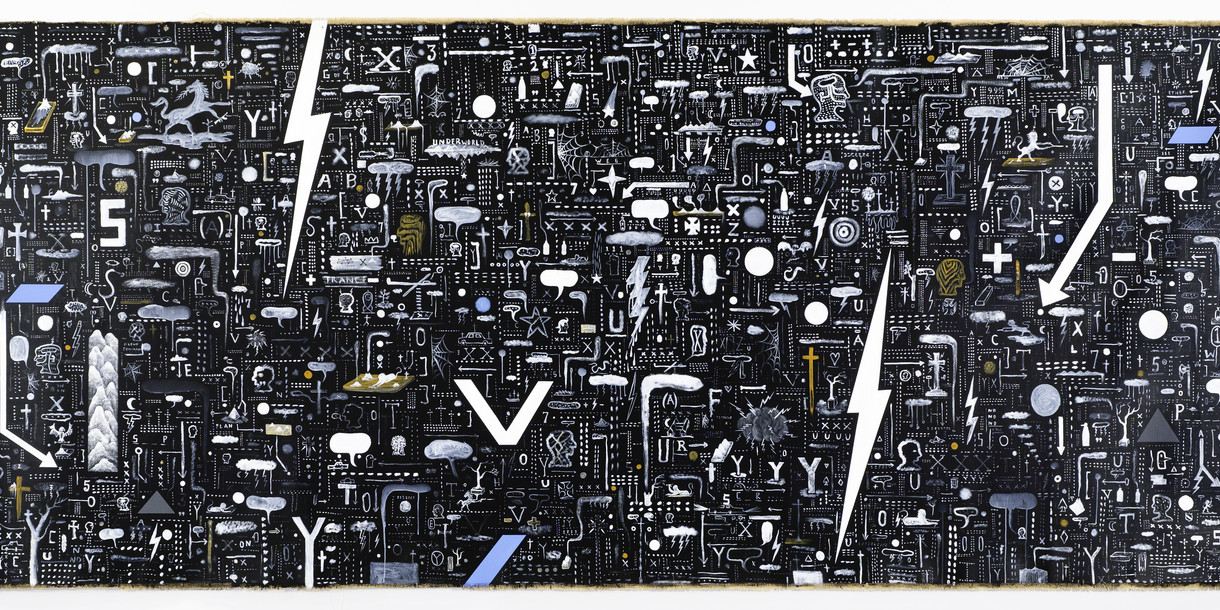

The danger with even a partial survey show like Cotton's is that it will summarise things all too well, leaving viewers feeling that they know exactly who the artist is and where he's coming from. But Cotton's new works—the bats, the targets— seem custom-made to knock such certainties out of the gallery. His biggest hit (so to speak) in this new mode is the painting reproduced below, a vast target on which he's floated a peculiar collection of images: a sparrow, a billiard ball, a skull, another head, a slice of sky with an abstract moon in it.

One can start by looking for family ties amongst these objects, focusing, perhaps, on the vanitas qualities of the skull, bird and head—each one associated in some way with the brevity and fragility of life. But the visual effect of the painting works fiercely against this connect-the-dots approach. Painted with great surety in a palette of pinks, greys and clarion blues, the target seems to sit right up on the painting's surface; it doesn't recede or open up atmospherically. So when Cotton drops modelled forms in front of it, they pop out from the flatness aggressively—like separate sounds bouncing into the room off the visual equivalent of a kick-drum.

Shane Cotton Head #!?$ 2009–12. Acrylic on linen. Private collection

Looking longer, what starts to build is an insistent staring quality: all those heads, dots, balls and circles eyeballing you individually; and then, pressed up behind them, the massive 'eye' of the target itself. What's Cotton up to? I think there's an answer right there on the canvas, where two words spell out the title—Head #!?$. As in, 'head-fuck'. As in, something custom-designed to unsettle our sense of the order of things. The word 'unsettle' is crucial. For much of his career Cotton has been known as an artist preoccupied by place: one who grounded Māori stories and imagery afresh in the tradition of New Zealand landscape. But if the new works in The Hanging Sky are any measure, what Cotton wants today is to un-ground his images: to cast them out into a strange open space where we can observe them without rushing into judgement.

Justin Paton

Senior curator