A Tale of Two Chiefs

Akaroa. Whites Aviation Ltd :Photographs. Ref: WA-24392-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22328245

If you have recently visited He Taonga Rangatira: Noble Treasures at the Gallery you will have been struck by Fiona Pardington's two large photographic portraits of lifelike busts of Ngāi tahu tipuna (ancestors).

With the intricate tracings of moko clearly visible on their brow and cheeks, they have their eyes closed in patient repose. The closed eyes—a necessary part of the cast-making process—give these two rangatira (chiefs) a vulnerability that one feels they would have been careful not to show in their lifetime. This sense of intimacy and vulnerability makes sustained viewing of the portraits uncomfortable, almost in deference to the subjects. Maybe they make you feel that you are trespassing in a highly personal moment. Or, if these are your ancestors, your impulse may be to walk up and hongi the men.

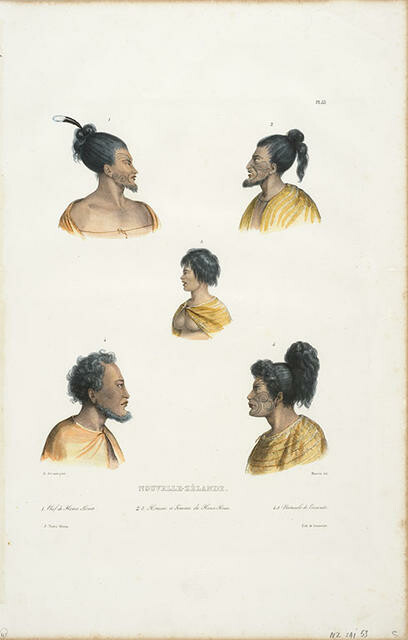

The two busts that Pardington has photographed were made by Pierre-Marie Dumoutier, the assistant naturalist on Dumont d'Urville's second voyage to new Zealand. the casts for the busts were taken while d'Urville's ship the Astrolabe was in Otago harbour, sometime between 30 March and 3 April 1840. Dumoutier made the casts as part of his work as a phrenologist—a now discredited 'pseudo-science' that sought to find a connection between the size and shape of a person's skull and a range of personal characteristics. In total, he made four busts while he was in new Zealand: three at Otago and one at Kororāreka (Russell). On the voyage as a whole he made fifty busts of indigenous people, which are now in the Musée de l'homme in Paris.

The ancestors depicted by Pardington have been identified as the closely related Ngāi Tahu rangatira Takatahara (also known as Tangatahara) and Piuraki (also known as John Love Tikao). For George Tikao, a direct descendant of Piuraki's brother Tāmati and also closely related to Takatahara, seeing the portraits is like meeting his ancestors face-to-face: 'the images themselves, if I knew these old people at that age, I would say that those images would be very lifelike. When I see them today, I can see the very likeness of those people at the time.'

George was, however, surprised that the ancestors had allowed casts to be taken of their heads: 'I know that our people were very wary of their heads. The ūpoko, the head, was a very tapu part of the elders, of the chiefs, and it was quite a surprise to me that they allowed their heads to be shaved and casts to be taken.'

However, he says that they had had a lot of contact with Europeans by then, which may explain why they agreed to undergo the mould-making process: 'Piuraki had travelled the world. Even though they would have been a wee bit sceptical about having their heads placed in casts they wouldn't have been overly concerned.'

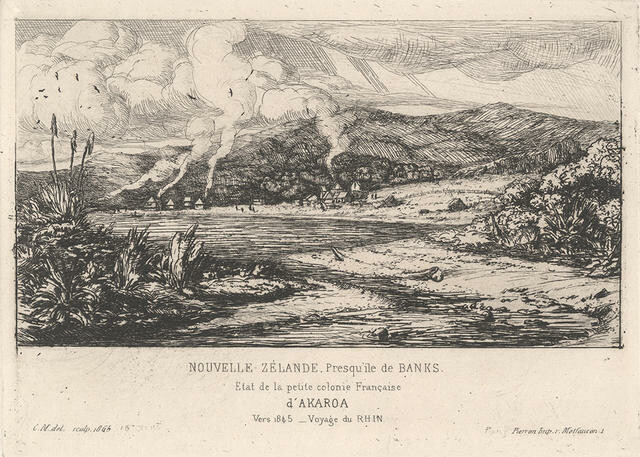

Of the Ngāti Irakehu hapū of Ngāi Tahu, Takatahara was one of the leading northern ngāi tahu fighting chiefs during the 1827 to 1839 wars with Ngāti Toa, and was responsible for the killing of Ngāti Toa ariki (paramount chief) Te Pēhi Kupe at Kaiapoi in 1829/30. Although taken captive after the fall of Kaiapoi Pā in 1832, he soon managed to escape into the bush in the vicinity of Duvauchelle, at the northern end of Akaroa Harbour. He then became one of the leaders of the Taua Iti (1832–3) and Taua Nui (1833–4) expeditions against Ngāti Toa.

Although a Horomaka (Banks Peninsula) chief, Takatahara spent a considerable amount of time further south between 1836 and 1840. His final years were spent on the western shore of Akaroa Harbour, where he was buried on 13 December 1847. A monument to Takatahara was erected at Wairewa (Little River) in 1900 and a copy of the bust photographed by Pardington is on display at Akaroa Museum.

Piuraki could whakapapa (trace his genealogy) to many of the principal Ngāi Tahu hapū. Like Takatahara, Piuraki lived on the western shore of Akaroa Harbour and at other places on Banks Peninsula. According to his nephew, Teone Taare Tikao, he was a tall man, standing 1.93m, and proficient with the taiaha. Piuraki was captured by Ngāti Toa at Kaiapoi in 1832, along with his mother, father and brothers. His mother, Hākeke, managed to escape but the rest of the family were taken to Kāpiti Island and imprisoned. Some time later Piuraki joined the crew of a whaling boat and sailed to Europe; he subsequently spent a number of years in France and England and is said to have become proficient in seven languages.

Piuraki was one of two chiefs who signed the Treaty of Waitangi at Ōnuku (near Akaroa) on 30 May 1840, having returned to New Zealand shortly beforehand. Major Bunbury, the British officer responsible for treaty negotiations in the South Island, described him as 'an intelligent native', who was well dressed and spoke English well. His knowledge of European commerce saw him take the lead in land negotiations—knowing the true worth of land in European terms he became an active opponent of land sales and a persistent thorn in the side of the government.

At the end of his life Piuraki returned to Banks Peninsula, and to Pigeon Bay, where his wife and children were buried, the victims of one of the many epidemics of European-introduced diseases to afflict the local population. He died at Pigeon Bay in June 1852 and was buried at Kaiapoi.

Ross Calman

Ross Calman is a Christchurch-based writer and editor. He is of Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Toa and Ngāti Raukawa descent and is married to Ariana Tikao, who is a descendant of Piuraki's brother, Tāmati.

Sources:

George Tikao, interview 3 January 2011.

Harry Evison, Te Waipounamu: The Greenstone Island, Christchurch: Aoraki Press, 1993.

Marc Rochette, 'Dumont d'Urville's Phrenologist: Dumoutier and the Aesthetics of Races', in The Journal of Pacific History, vol.38, no.2, pp.251–68.

Acknowledgements:

He mihi nui ki a Ariana Tikao rāua ko Christine Tremewan.