B.

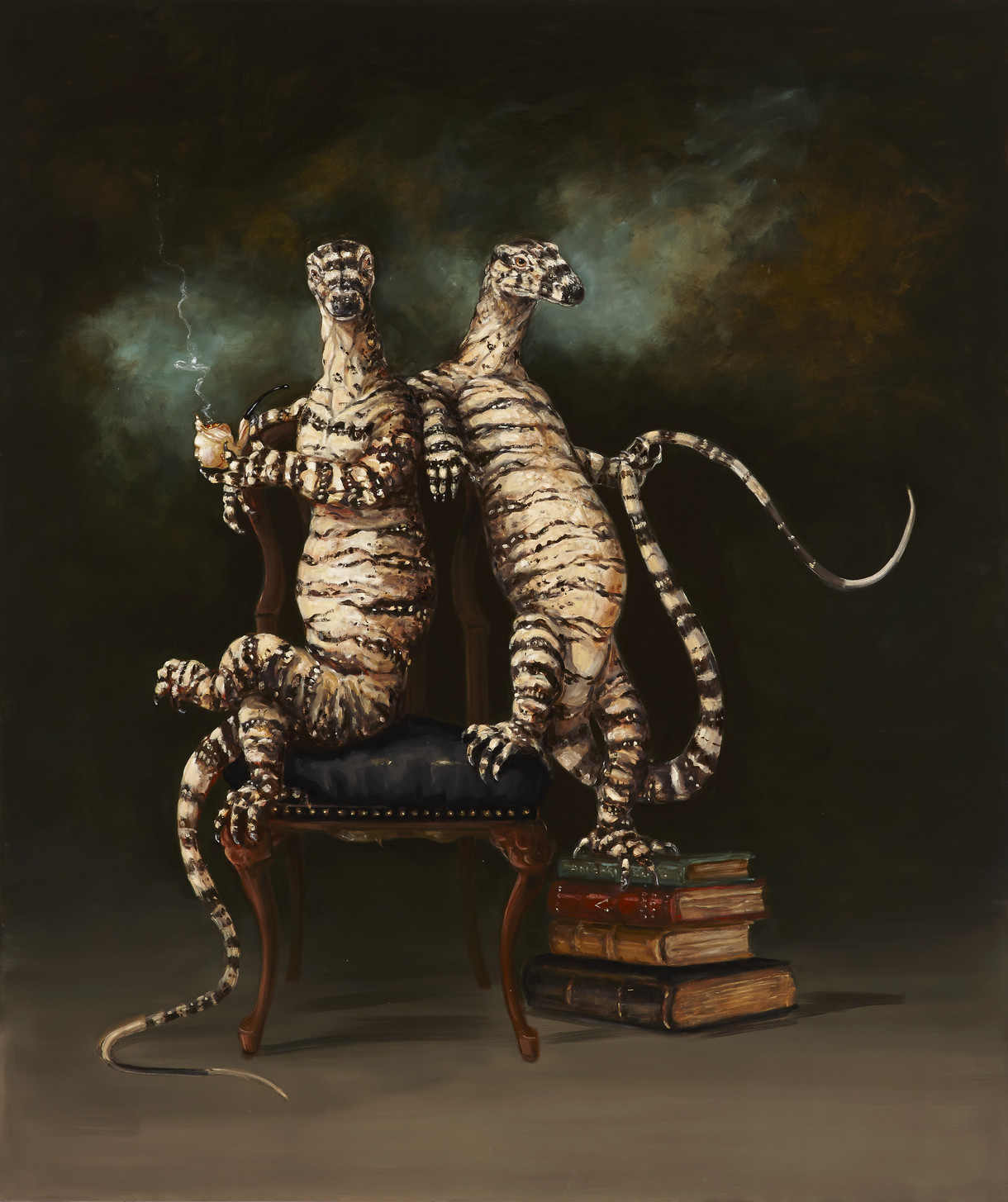

My Sister My Self by Michael Parekowhai

Collection

This article first appeared with the headline Top-stair sculpture in The Press on 30 April 2008.

If you've done your first year art history, you're probably familiar with the story of How Sculpture Fell from Grace.

Michael Parekowhai My Sister, My Self 2006. Fibreglass, mild steel, wood, automotive paint. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2008. Reproduced courtesy of the artist and Michael Lett

Once upon a time, this story goes, sculpture lived up on a pedestal. Whether the object in question was a portrait in marble or a figure in bronze, it was always lifted up out of the ordinary by its plinth - made noble, special and elevated.

Then came the convention-shattering twentieth century and kicked sculpture off its perch. Broken into pieces, clattering across floors, tumbling out into the wider world, sculpture developed what purists saw as a case of bad posture. Sculpture at its most basic tends to combine gravity and grace. But when you look at sculpture of the last half-century, with all its spills and scatterings, it can seem that gravity has triumphed, pulling it relentlessly downwards.

Unless the sculpture you're looking at is by Michael Parekowhai. In a series of unforgettable recent works involving performing seals, a billiards table and an upended Steinway piano, the Auckland artist has defied the rules of gravity with showmanly glee and panache. Anyone keen to see him do so again should in mid May visit the Christchurch Art Gallery's foyer, where one of his recent balancing acts will be taking up residence at the top of the marble staircase.

Parekowhai loves to take utterly familiar things and render them bigger and glossier. He has enlarged cartoon rabbits to the size of science-fiction monsters, pick-up sticks to the size of spears, and plastic 2-dollar shop sheriff's badges until they look as grand as shields.

In My Sister, My Self he offers another gleaming tribute to a humble New Zealand object - namely the ornamental seals you can still see here and there in New Zealand front yards and playgrounds (the ones I remember best rise from the corners of the blue paddling pool in the Oamaru Botanic Gardens). Whereas those seals were made of concrete, Parekowhai moulds this one from fibreglass and seals it in a slippery skin of automotive paint. And where those concrete seals ordinarily held a ball on their noses, Parekowhai has given this one a stranger trophy to balance: a stool with a bicycle wheel attached to it.

And not just any old bicycle wheel and stool. What you'll see poised in mid-air as you climb the gallery stairs is an immaculate, hand-built copy of one of the most famous ordinary objects in the history of modern art - the wheel that artist Marcel Duchamp turned upside down and attached to a stool in 1913 and later described as a ‘readymade', a seemingly casual gesture that turned the whole practice of sculpture on its head. Sculptors, Duchamp seemed to be saying, no longer needed to make new things, but simply could choose them from a world already jostling with mass-produced objects. Sculpture's trip down from the pedestal started there.

An artist described by Willem de Kooning as a ‘one-man movement', Duchamp was the master of a certain kind of brainy creative mischief. There is no one in New Zealand better qualified than Parekowhai to serve that brand of mischief back to the master. From the boxing gloves he carved at art school and inscribed ‘D Champ, ‘68' (the year Duchamp died and Parekowhai was born) to an earlier version of the Bicycle Wheel that he hand-carved from oak and kauri and titled After Dunlop, you could organise a whole show consisting solely of Parekowhai's replies to the Frenchman.

Equally, there is no better place than the Christchurch Art Gallery for Parekowhai's latest round with Duchamp. Back in 1967 at the Robert McDougall Art Gallery local viewers had the chance to see a huge survey of Duchamp's works, including a version of the Bicycle Wheel. They were also refused the right to see two of those works, due to an infamously prudish bit of censorship. And now, forty-one years later, the wheel rides back into Christchurch on the nose of a South Pacific circus animal. I like to imagine the unflappable Duchamp glancing down through clouds of cigarette smoke and murmuring his approval.

These days it's not cigarette smoke that makes Duchamp a hard artist to see, but the sheer quantity of comment and counter-comment that swirls around his enigmatic objects. One of the joys of Parekowhai's sculpture is that it pulls Duchamp out of the world of footnotes and grainy photographs and back into our physical space. Patiently recreating the bicycle wheel and flipping it up onto this dazzling plinth, Parekowhai leaves us in no doubt that Duchamp's legacy is still up for grabs, here and now, by whoever finds a use for it. If there's a touch of reverence in this recreation, what comes across much more strongly is the spirit of play - Parekowhai rummaging in the toy box of modern art and lofting what he finds there in the air.

Along the way Parekowhai makes the case for an underrated sculptural virtue - poise. Not just the technical poise required to balance a piano on the nose of a seal, but the cultural poise needed by any artist who wants to move without strain between the suburbs of west Auckland and the artistic traditions of Europe. So what you'll see first and foremost at the top of the stairs is a sculpture that's perfectly balanced - an object made by someone with a great eye for the way objects act on other objects and hold the space around them. But you'll also see a sculpture that's perfectly balanced in the bigger sense - between the local and the international, the circus-tent and the art gallery, the ordinary and the extraordinary.

And that is why, despite Duchamp's part in this work, I think the real star of this sculpture is the seal. Rising up on its flippers in a ripple of black to perform its improbable trick, the seal - like Parekowhai himself - is a peerless sculptural performer. If this artwork had a voiceover, it would say ‘voila'.

Justin Paton