B.

Tomoe Gozen pulling the ear of Nagase Hangan in the presence of Tezuka Tarô Mitsumori, Kiso Yoshina

Collection

This article first appeared in The Press on 1 November 2006

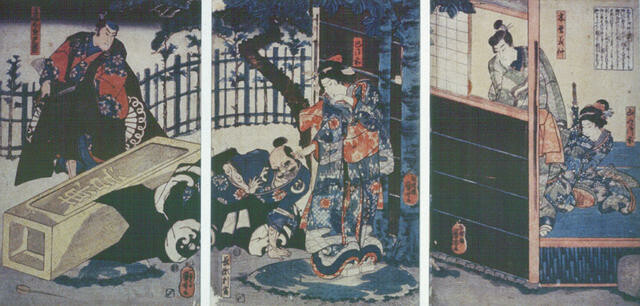

Standing beneath a leafy bough, and immaculately attired in swathes of red and blue, a petite Japanese woman looks down, bends - and does a surprising thing. Beneath her, and apparently at her mercy, is a traditional samurai warrior, a large and muscular man. The woman, however, pinches the lobe of his ear and inflicts excruciating pain. It is a curious scene. As an ‘ukiyo-e' woodblock print, it is the central panel of a triptych by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798-1861).

Utagawa Kuniyoshi Tomoe Gozen pulling the ear of Nagase Hangan in the presence of Tezuka Taro Mitsumori, Kiso Yoshinaka and Yamabuki Gozen circa 1843. Woodcut. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1953

In 1853, ten years after Kuniyoshi made this ukiyo-e print, Japan ended more than 200 years of self-imposed isolation from the rest of the world, and in 1867 opened up to trade with the West. Thus, works on paper such as this one began to appear outside of Japan, and were seized upon by western artists and collectors, often at first discovered as wrapping for exported porcelain or furniture. As ukiyo-e prints became better known, their distinctive qualities of colour, line and composition also began to deeply influence the work of leading European artists. For names such as Degas, Monet, van Gogh and Toulouse-Lautrec, ukiyo-e - the art of ‘the floating world' - became a significant presence.

The term ‘ukiyo-e' appeared in the mid 17th century, as an ironic wordplay on the Buddhist name for the earthly plane, and implied the transitory nature of human existence, with its unending hardship and human frailty. Eventually, the meaning expanded to imply pleasure seeking as a form of escapism, and later also the meanings of ‘present day' and ‘latest fashion'. In the urban centres of Japan in this period, including Edo (modern day Tokyo), ‘ukiyo-e' represented the prevailing lifestyle, with its moving parade of entertainments, fashions and fleshly pleasures.

Edo-based Utagawa Kuniyoshi was one of the more well-known ukiyo-e woodblock print artists, and one who found his lifeblood in the popular kabuki theatre. As the son of a silk dyer, and a member of the urban artisan class, Kuniyoshi's role as artist held no elevated status. He was also part of a team, working alongside a wood engraver, a printer, and the publisher who coordinated and paid for production, with livelihood and survival dependent on high output. Kuniyoshi must have worked like a modern comic book artist, and is said to have produced many thousands of designs. With most of his work connected to kabuki theatre, his prints were intended to be enjoyed briefly as inexpensive souvenirs of the latest stage productions. In elegant line and vivid colour, actors were celebrated as heroes and heroines, courtesans and warriors. Works such as these were not exhibited or framed, and individual prints sold for the equivalent price of a bowl of noodles.

Kuniyoshi is most well-known for his musha-e, or warrior prints, that began to appear in the early 1840s - the period in which this print was made. In 1842, the Shogun government issued their Tenpô Reforms, meaning that artists like Kuniyoshi were no longer allowed to create depictions of the stage. Many theatres were closed or relocated, and prints of beautiful women and actors were disallowed. The decrees were intended to curtail every expression of frippery and extravagance, with the aim of preserving social order in response to threats that were both internal (as highlighted by recent famines) and external (with news of easy recent British victories in China). Such rules were difficult to enforce, however, and Kuniyoshi dealt with the issue by adjusting his direction, and depicting characters from the stage who also happened to be popular historical figures. From 1842-6, he made several large series of warrior prints and triptychs, all of these illustrating scenes from history, legend and popular romance, but also based on current theatrical productions.

This work depicts the stage version of the tale of Tomoe Gozen, an extraordinary 12th century female samurai warrior who first appears in the Heike Monogatari, an epic of Japanese literature dating from the early 13th century. The epic tells the story of the rival Minamoto and Taira clans, and their long and typically violent struggles for power. In it, Tomoe is described as being extremely beautiful, a remarkably strong archer, and in her capacity as a swordswoman "a warrior worth a thousand, ready to confront a demon or a god, mounted or on foot".

The central panel of the triptych captures a pivotal moment in her story. Tomoe Gozen (‘Lady Tomoe') is the mistress and senior captain to Minamoto General Kiso Yoshinaka, who has been wounded, and is seen in an adjoining print, keeping his distance behind a paper screen. The injuries have been inflicted by Nagase Hangan, a feared samurai envoy from the rival Taira clan, but Tomoe fiercely defends Yoshinaka's ambitions as she pins the man to the ground. The print, however, conveys the stage version, and full details of the original tale are withheld. In that version Tomoe is less elegantly attired in armour, and twists off the man's head.

Though not perhaps an ideal role model, Tomoe Gozen was a captivating subject for many ukiyo-e artists, and was portrayed many times by Kuniyoshi in single prints and triptychs. She also remains a celebrated cultural figure, and strikes a strangely contemporary note. As one of very few authentic female samurai, and renowned for her exceptional beauty and strength, Tomoe is remembered in annual festivals and parades, and has also provided inspiration for Japanese moviemakers and manga comics. Traces of her also seem to exist in movies such as ‘Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon', or ‘Lara Croft, Tomb Raider'. Representing unswerving loyalty and strength in the face of daunting opposition, Tomoe Gozen was clearly a force not to be messed with.

Ken Hall