Wunderbox

By Tracy McCaw

Wunderbox, curated by Justin Paton, ran from 28 November 2008 - 15 February 2009.

Here are some of the works from the exhibition.

A piece of coral. A unicorn’s horn. A clockwork robot. A globe of the known world …

These are just some of the objects you might have found inside the doors of a seventeenth-century wonder cabinet. Variously known as wonder rooms, cabinets of curiosity and wunderkammer, wonder cabinets emerged in the late sixteenth century and had their golden age in the seventeenth. For patrons and collectors newly fascinated by the world beyond Europe, wonder cabinets offered a kind of portrait of the world in miniature – a finite space filled with a sampling of the world’s infinite strangeness.

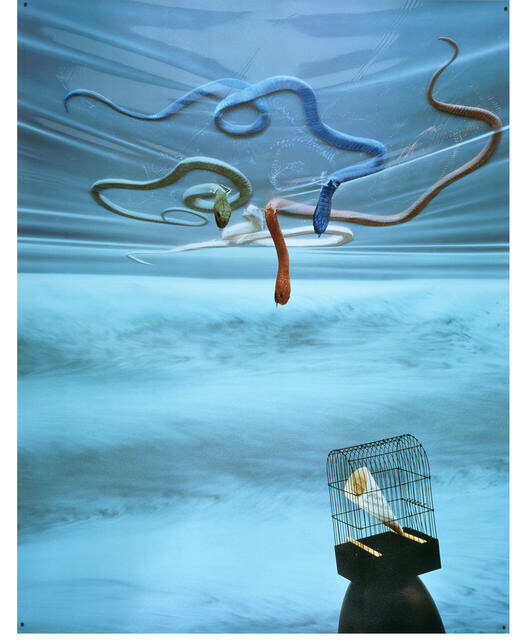

Drawn largely from the contemporary collection of Christchurch Art Gallery, Wunderbox is an exhibition of secretive spaces, model worlds, fictitious collections and idiosyncratic trophies by contemporary New Zealand artists. Ranging from one of the largest works in the collection to one of the smallest, it’s an exhibition about our attempts to collect and categorise the world. It’s also, more importantly, about the moments of doubt, wonder and pleasurable confusion that arise when the world slips through those categories.

As the Gallery moves towards a major rehang of its permanent collection in 2009, Wunderbox also offers an opportunity to reflect on the ways public galleries accumulate and preserve artworks. For the artists in this show, collecting is not a dry and dutiful accumulation of objects but a charged and imaginative act.

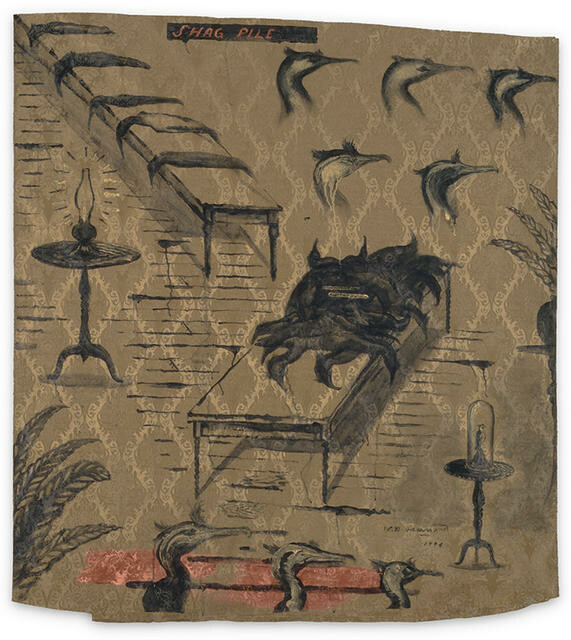

Bill Hammond Shag Pile 1994

Bill Hammond led one of the most influential tendencies in New Zealand painting of the late 1990s – Post-colonial Gothic. Shag Pile is one of his many paintings inspired by the nineteenth-century campaigns to catalogue New Zealand’s dwindling native species, in particular the efforts of Walter Lowry Buller. The contradictions of Buller’s character – a recorder and chronicler of birds who killed and stuffed many – have made him a figure of fascination not only for Hammond but for sculptor Warren Viscoe and playwright Nick Drake. In Shag Pile, Buller’s campaign plays out like a bad dream projected on the patterned walls of a claustrophobic Victorian parlour, where New Zealand spotted shags are heaped, laid out for processing, and sealed under bell jars.

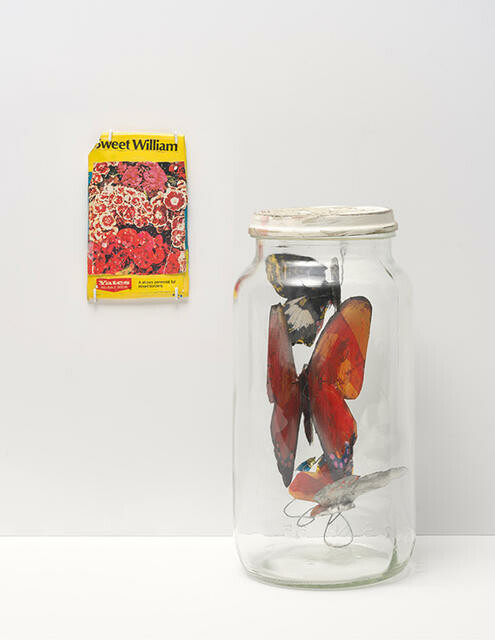

Christine Hellyar Body parts: White china cupboard 1989-1990

The artist as collector, recycler, and natural historian, Christine Hellyar has never subscribed to the idea that sculptures should be grand and singular objects. The word ‘sculpture’ seems inadequate to describe many of her works, which look like artefacts imported into the gallery from some other time and place. With their weathered natural forms, her artworks remind us of the vast cycles of change and transformation that govern the life of things. But they also mark the distance between those cycles and the experience of contemporary gallery-goers, as we peer in through glass at objects whose names and functions we scarcely recognise.

Richard Killeen Book of the Hook 1996

Richard Killeen came to the fore in the 1960s as a painter of oddly stilled and poster-like scenes of suburban New Zealand life. He consolidated his growing reputation in the late 1970s when he made the first of his ‘cut-outs’, in which compositional elements were cleanly sliced from pieces of aluminium and allowed to hang in variable arrangements on the gallery wall. For the last two decades Killeen has expanded and deepened the range and possibilities of the ‘cut-out’ format. By the mid-1980s, each individual piece had begun to bustle with images culled from a vast range of sources. In Book of the Hook he concocts a pseudo-museum of anthropological fragments, all 253 of which come from an invented organisation called the ‘Hook Museum’. Recent work by Killeen can be seen on the Worcester Boulevard façade of the Gallery, where his vast billboard The Gathering recently went on show.

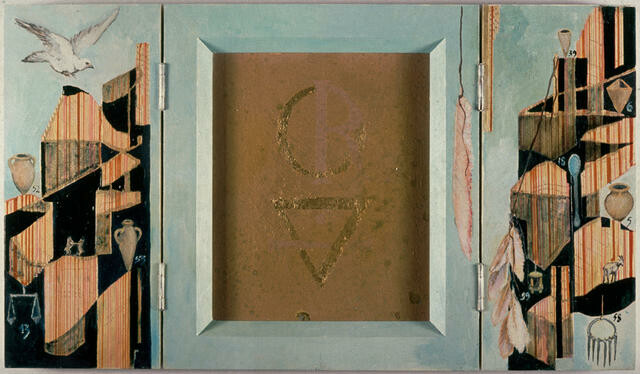

Julia Morison Amalgame 48 1991

In 1990 Christchurch artist Julia Morison won the Moët & Chandon Fellowship and went to live and work in the Champagne region of France. In preparation for the journey, Morison prepared a number of boxes with hinged doors inspired by Russian icons in the collection of Dunedin Public Art Gallery. Used by devout travellers as portable chapels, these boxes greatly appealed to Morison as she embarked on her own travels.

Morison initially completed fifty-five painted ‘books’. The doors of each feature one of fifty-five logos from an earlier work of Morison’s called Vademecum, and open to reveal an alchemical sign surrounded or entwined with imagery that Morison collected on her own real and imaginative travels, much of it gleaned from old encyclopaedias – collections of another kind.

The original installation of Amalgame took place in a crypt below a deconsecrated chapel. Morison arranged the fifty-five books on rows of benches below reading lights. They were offered as meditations, to be opened and quietly ‘read’ in a former place of the dead.

In 1990 Christchurch artist Julia Morison won the Moët & Chandon Fellowship and went to live and work in the Champagne region of France. In preparation for the journey, Morison prepared a number of boxes with hinged doors inspired by Russian icons in the collection of Dunedin Public Art Gallery. Used by devout travellers as portable chapels, these boxes greatly appealed to Morison as she embarked on her own travels.

Morison initially completed fifty-five painted ‘books’. The doors of each feature one of fifty-five logos from an earlier work of Morison’s called Vademecum, and open to reveal an alchemical sign surrounded or entwined with imagery that Morison collected on her own real and imaginative travels, much of it gleaned from old encyclopaedias – collections of another kind.

The original installation of Amalgame took place in a crypt below a deconsecrated chapel. Morison arranged the fifty-five books on rows of benches below reading lights. They were offered as meditations, to be opened and quietly ‘read’ in a former place of the dead.

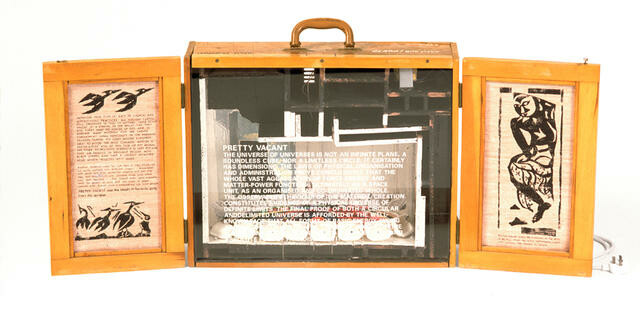

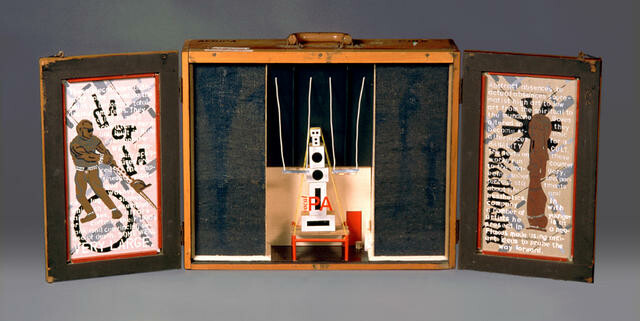

Terry Urbahn Africa 1997

In the late 1990s Terry Urbahn set to work embellishing a series of display cases that had been constructed almost two decades earlier by the National Museum Education Service. With their text panels, diagrams and tiny models, these cases sought to instruct school children about the lives of Māori, Aboriginal Australians, and other ‘tribal’ cultures. In his 1997 series Urban Museum Reality Service, Terry Urbahn thoroughly disrupted the old lessons. Overlaying the educational texts with a blizzard of mixed messages and placing models of his own artworks within, he breathes unruly contemporary life into these old-fashioned ‘small worlds’.

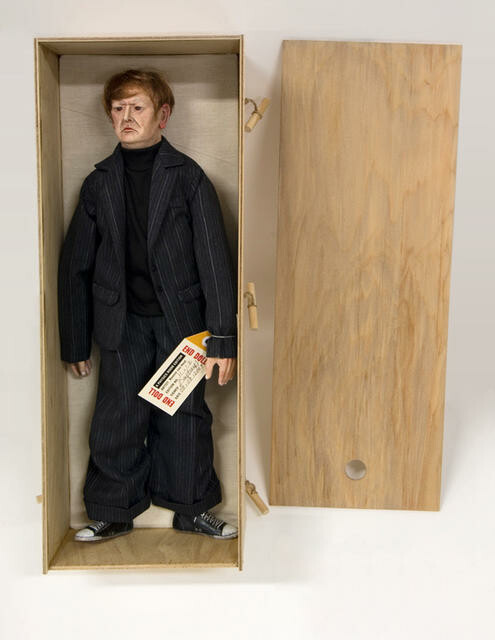

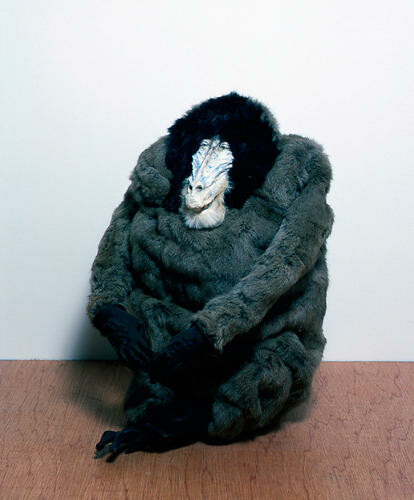

Steve Carr A Shot in the Dark (Bear Rug) 2008

Technical finesse and mischievous humour characterise the photographs and sculptures of Auckland artist Steve Carr. Rather than pursuing grand or heroic emotions, the traditional subjects of carved figurative sculptures, this artist is interested in minor-key qualities like self-deprecation, humility, mildness and tameness. The last word is especially relevant to A Shot in the Dark (Bear Rug), which looks like the kind of gruesome trophy that might rest on the floor of a late-nineteenth-century gentleman’s den, smoking room, or house museum. Bears epitomise physical threat, but this one has been tamed many times over – pushed out of life and into art. First it was shot, then eviscerated and partially stuffed, then turned into a carving, and finally displayed in an art gallery. All artworks are trophies of a sort, pieces of life that have been stilled and stored, but Carr brings this tension between stillness and life to an unusually intense pitch. How much ‘bite’ does any piece of life retain by the time it arrives in a gallery?