William Dunning

Aotearoa New Zealand, b.1959

Colonization Triptych

- 1999

- Acrylic on canvas

- Purchased, 1999

- 1804 x 1556mm

- 99/321.1-3

Location: Dame Louise Henderson Gallery

Tags: beards, buildings (structures), chairs (furniture forms), checker pattern, cloaks, colonization, families, fences, frames (furnishings), furniture, history paintings, houses, interior, kettles (vessels), landscapes (representations), men (male humans), moko, paintings (visual works), people (agents), portraits, soldiers, swords, tables (support furniture), treaties, trees, triptychs, uniforms, wars

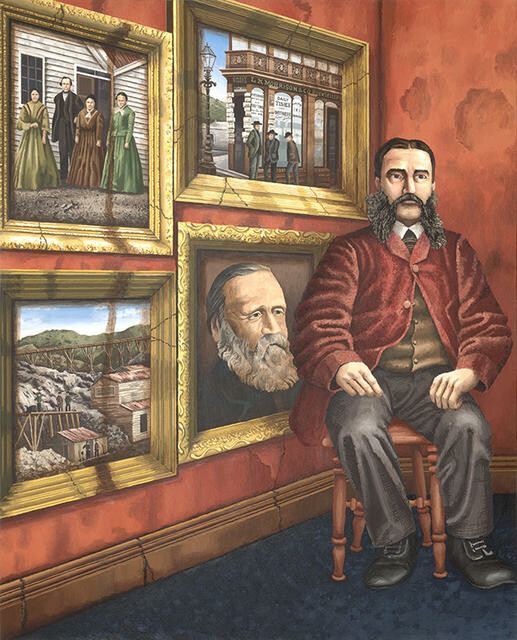

William Dunning’s Colonization Triptych presents important moments and figures from Aotearoa New Zealand’s colonial history through paintings within a painting, showing us the layers, cracks and stains of our nation’s past. In the left panel is Julius Vogel, a newspaper editor and politician in Ōtākou Otago. He sits in front of scenes of early settler life in Te Waipounamu South Island – Ōtepoti Dunedin in the 1860s, gold mining at Blue Spur inland from Hokitika – and a portrait of William Fox, leader of the New Zealand government. Vogel was one of Fox’s ministers known for his ‘expansionist’ policy to hugely increase immigrants to Aotearoa, grow national infrastructure and purchase and develop Māori land for European settlement. In the centre panel is an interpretation of Giovanni Bellini’s famous painting Transfiguration of Christ. Dunning replaces Jesus with colonial governor William Hobson, and Moses and Elijah with a deed-bearing settler and Māori chief.

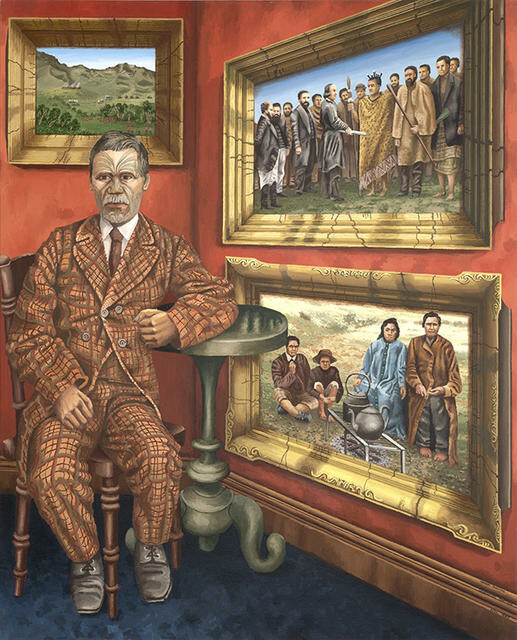

Opposite Vogel in the right panel sits the great Ngāti Maniapoto rakatira and military strategist, Rewi Maniapoto. In response to the colonial invasion of Waikato ordered by governor George Grey in 1863, Maniapoto led his iwi to war. When ordered to surrender during the siege at Ōrākau pā in 1864, shown by Dunning in the small painting in the right-hand panel, Maniapoto spoke the famous words, “Ka whawhai tonu mātou, āke, ake, ake!” We will fight on, forever, and ever, and ever!

Ngāti Maniapoto ~ tribal group of the King Country area in Te Ika-a-Māui North Island

rakatira ~ chief

iwi ~ tribe

pā ~ fortified village

He Kapuka Oneone – A Handful of Soil (from August 2024)

See the Transfiguration of Christ by Giovanni Bellini (1430-1516), Museo di Capodimonte, Naples.

Exhibition History

See this work extra close-up.

He Waka Eke Noa, 18 February 2017 – 18 February 2018

William Dunning’s Colonization Triptych presents history as an uncomfortable place filled with cracks and stains. In a gallery of paintings within a painting, it places colonial Prime Minister Julius Vogel in the same room as Waikato Māori leader Rewi Maniapoto, each flanking an adapted version of Giovanni Bellini’s circa 1487 Transfiguration of Christ. Dunning’s reworking, however, replaces Jesus with early colonial governor William Hobson and Moses and Elijah with deed-bearing settler and Māori chief, substituting Bellini’s startled disciples with generic Māori figures. In dealing with displaced, changing authority and rulership, Colonization Triptych tells of the artist’s abiding awareness of the government-led injustices of the colonial past. The stiff awkwardness of the figures recall waxwork museum dioramas or early photographic studio portraits, and echoes the discomfort still easily enough associated with this past.

Keeping Time, 23 May – 31 August 2008

A fascination with history is at the heart of William Dunning’s work, but the past he presents here is oddly lifeless – the kind preserved, even imprisoned, in worthy museum dioramas. Colonial politician Julius Vogel and famed Māori leader Rewi Maniapoto sit uncomfortably in a stuffy Victorian room, hemmed in by images of capitalism and colonisation. Between them is Dunning’s secular interpretation of Bellini’s 15th-century Transfiguration of Christ, re-styled for a colonial New Zealand context. Governor William Hobson takes Christ’s place, while a Pākehā settler and Māori chief, each holding a land deed, stand in for Moses and Elijah. Dunning uses this traditional setting to depict a watershed moment in New Zealand history – the formalisation of the partnership between Māori and the Crown – but any sense of promise is undermined by cracks and stains that mar the paintings and wallpaper. Like the waxwork-still Vogel and Maniapoto, we can only watch and wait as the composition begins to crumble under the strain of unfinished business.

(Keeping Time, May 2008)