Mary Barrett Horse c. 1936. Bronze. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū

Morris Dancing in the Modelling Room

The Art and Influence of Francis Shurrock

Arriving in Ōtautahi Christchurch must have been like arriving on another planet for Francis Shurrock. It was 1924, and he had travelled half-way around the world from England to take up a position as modelling and art craft master at the Canterbury College School of Art. Indeed, one of his pupils there, Juliet Peter, later described him as an “alien”, for the fresh approach to teaching that made him stand out from other teachers at the school.1 Nevertheless, Shurrock made Ōtautahi his home and never returned to England.

Arriving in Ōtautahi Christchurch must have been like arriving on another planet for Francis Shurrock. It was 1924, and he had travelled half-way around the world from England to take up a position as modelling and art craft master at the Canterbury College School of Art. Indeed, one of his pupils there, Juliet Peter, later described him as an “alien”, for the fresh approach to teaching that made him stand out from other teachers at the school.1 Nevertheless, Shurrock made Ōtautahi his home and never returned to England.

The thirty-six-year-old was part of a generation of British artists that came to Aotearoa New Zealand in the 1920s. They were brought out under the Department of Education’s La Trobe Scheme – an attempt to raise the standards of art education by importing new, modern attitudes to art. Most La Trobe Scheme artists were graduates of London’s Royal College of Art and, in addition to Shurrock, their number included Robert Field, William Allen, Roland Hipkins and Christopher Perkins.

Shurrock was a welcome addition in an art school with a reputation for being conservative and traditional. His free spirit and modern outlook on art and life endeared him to students and contemporaries alike, and he became a popular teacher, introducing a new approach to self-expression. Among those he taught were a generation of young Waitaha Canterbury artists that included Chrystabel Aitken, Florence Akins, Mary Barrett, Cecil Dunn, Jim Allen, Molly Macalister, Alison Duff, Bill Sutton and Juliet Peter. Comments from many of these artists suggest that he was a kind-hearted man who inspired his students to broaden their thinking about art – Sutton later recalled that “we learned to think from ‘Shurry’”.2

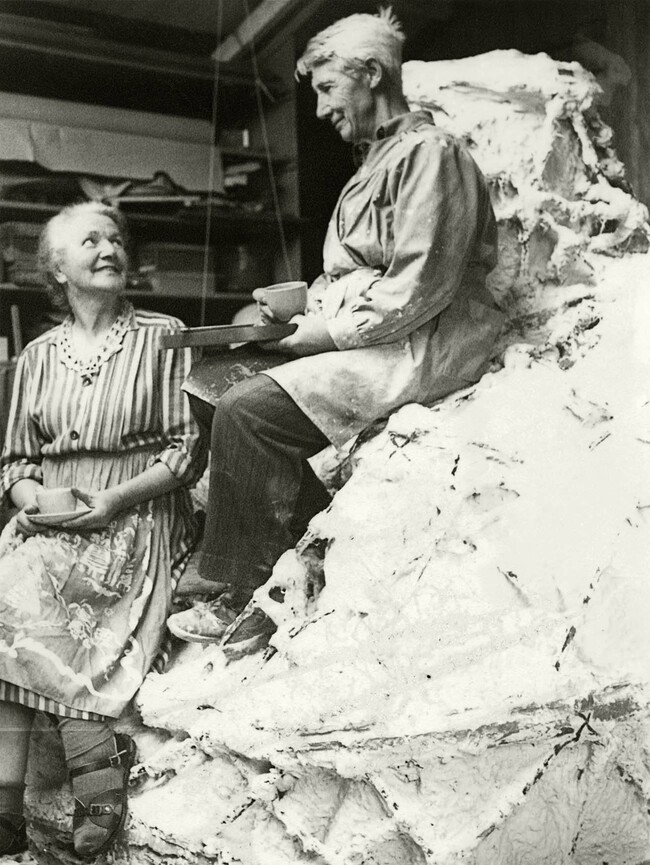

In November 1925, Shurrock married Elizabeth Hilson who was his close companion and supporter for almost fifty years until her death in 1972. The pair were fondly referred to as Mr and Mrs Shurrie by students and friends.3 Looking at photographs of the Shurries and gatherings at their house in Brockworth Place, Riccarton you get a sense of the couple’s good humour and generous spirit – qualities that left a lasting impact on Shurrock’s students.

Highly regarded as a sculptor, Shurrock received several public commissions during his career, including statues of William Ferguson Massey for Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington in 1929, James Edward Fitzgerald for Ōtautahi in 1934, and the monumental Otago Centennial Memorial (1952–4) in Ōtepoti Dunedin. He was an excellent wood-engraver and an early adopter of the linocut during the late 1920s, encouraging his students to take up the medium as well. The nature of these prints, where imagery is carved into the blocks to form an image in relief, must have appealed to the sculptor for whom surface was central.

Alison Duff Frank Sargeson 1963. Bronze. Commissioned by Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council of New Zealand and presented to the Auckland Public Library 1965, Auckland Council Art Collection

Shurrock also had a deep love of Japanese art and culture and brought a large collection of ukiyo-e / colour woodcuts out from England. His interest in Japanese art began early in his career and around 1912, while studying at the Royal College of Art, he made a kimono-inspired robe which he painted with elaborate Japanese influenced decorations. He enjoyed sharing his knowledge of ukiyo-e printmaking and the prints were freely lent to students and friends who showed an interest. With their sharply drawn outlines and subtle shifts in colour tones, Leo Bensemann’s 1933 watercolour Untitled (Taylors Mistake) and Rita Angus’s watercolour Mountains, Cass (1936) both reveal their influence.

Alongside his work as a sculptor Shurrock had a deep love of folk dancing and music, which developed throughout the 1930s and into the 1950s. Folk music experienced a major revival in Britain during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as figures such as Cecil Sharp and Ralph Vaughan Williams sought to record and revive this fast-vanishing aspect of British culture. Shurrock imported numerous books of sheet music relating to Morris and sword dancing, many published by Sharp, which are now part of the Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū library archives. He became involved with a Morris dancing team that included William Allen, Florence Akins and Leo and Mary Bensemann. They performed at several WEA (New Zealand Workers’ Educational Association) summer school classes in Whakatū Nelson in the early 1940s. More than fifty years later, Juliet Peter could still recall hearing this group rehearse in the modelling room at the art school during lunch breaks, describing “the tumpety-tumpety tump as the devotees pranced to ‘Shepherd’s Hey’ or ‘Molly-on-the- Shore’…”4 One folk dance reviewer in 1940 commented “Mr Shurrock – perhaps more easily recognised as ‘Shurry’. Does he ever part with his Morris Baldrick and Bell-pads? We think we would hardly know him if he did. How he springs and capers and with what energy he strikes his partner’s stick; and with what infinite patience he directs our feeble attempts to learn elementary Morris and extricates us from a glorious mix-up of dancers and swords! Christchurch, for Mr and Mrs Shurry, we envy you.”5

![Chrystabel Aitken Untitled [Cat] c.1932. Ceramic. University of Canterbury Art Collection](/media/cache/a0/60/a060c28fa671c3c77385ea63af85ca99.jpg)

Chrystabel Aitken Untitled [Cat] c.1932. Ceramic. University of Canterbury Art Collection

Akins and the Bensemanns were also part of a folk recorder group that Shurrock formed, in which they all made their own instruments out of bamboo. He composed at least two original musical compositions for this group including one, ‘Jack’s Parrot’, that he described as an “original motif as given by his colleague at the art school, John N. [Jack] Knight after returning from War Service in the Solomons, where he had heard this parrot call in the bush.”6 This interest in folk music and dancing from Shurrock and his friends was a forerunner to New Zealand’s folk music revival in the 1960s. Photographs and film footage of Shurrock and his friends dancing or posing with their newly made recorders indicate that these were enjoyable social occasions and the friendships formed went beyond the traditional teacher / student relationship.

Many years after she had studied with him, Juliet Peter reminisced about what Shurrie meant to her:

My real teacher was Francis Shurrock … who presided over the modelling room in the School of Arts. He was unable to teach sculpture because the school, headed by Richard Wallwork, didn’t allow him the funds. He was a marvellous man. Instead of attempting to teach sculpture he provided for his students by talking to them and broadening their minds – blowing their minds, that was the term. He was my best ever teacher, and I think his influence has spread to a lot of people. I was actually taking the painting course at the School of Art but a lot of my time was spent in the modelling room.7

![Francis Shurrock Untitled [Architectural Piece] c. 1930. Ōamaru stone. University of Canterbury Art Collection](/media/cache/d1/fe/d1fe0a11c250e36e70f9a51abe23b713.jpg)

Francis Shurrock Untitled [Architectural Piece] c. 1930. Ōamaru stone. University of Canterbury Art Collection

Shurrock’s legacy continued to ripple outwards – not least through one of his most prominent students, Jim Allen, who became a pioneering figure in both art and art education in Aotearoa New Zealand. Allen had arrived at the University of Canterbury in 1946, after serving in the New Zealand Army in Europe, and then studying sculpture at the Istituto d’Arte in Florence. He graduated in 1948, and left for England to study at the Royal College of Art, where the comprehensive technical foundation he had received under Shurrock provided a clear advantage. On his return to New Zealand, Allen worked for the Department of Education, including as a field officer for Gordon Tovey’s experimental art initiative, the Northern Māori Project. In 1960, he joined the staff of the Elam School of Fine Arts, where he taught until 1976. There he transformed the sculpture department into a hothouse for conceptual and performance- based practices, which he termed ‘Post-Object’ art, and his students included Bruce Barber, Philip Dadson, Maree Horner and Peter Roche. Allen’s own artmaking responded to the zeitgeist and technologies of his generation, and often dealt in performance and the ephemeral. One of his most well-known projects, Contact, took place at Auckland Art Gallery in 1974. In three separate but related sequences, groups of performers first made contact using infrared emitters and receivers, then were encased in – and escaped from – tight bindings, and finally explored the articulation of their bodies by rolling in paint and moving around a plastic-covered room. The black-and-white photographs documenting the event show the assembled spectators range from the enraptured to the bemused. Visually, Contact seemed a world away from Shurrock’s work, and from the much more conventional sculpture Allen practised while training with him, and yet they represented his genuine attempt to achieve – in a relevant contemporary way – what Shurrock regarded as the primary purpose of art: that it “express life”.8 Many years later, Allen recalled Shurrock’s craft-based approach, which concentrated on how to do things rather than what one should do – letting each artist follow his or her own lead for that – and hinted at synergies with his own teaching style: “[P]eople have said that I didn’t seem to teach anything, and this always pleases me. My effort went into creating a supportive environment, encouraging experiment and exploration, insisting that people find their own answer rather than providing them with one.”9

Unknown photographer Elizabeth and Francis Shurrock in the studio 1953. Frederick Staub Papers, Robert and Barbara Stewart Library and Archives, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū

A 1939 photograph from the Canterbury School of Art shows a relaxed Francis Shurrock in the art room, examining a carved work with an engaged junior class, all women. Several went on to become successful sculptors whose legacies are now receiving fresh consideration in exhibitions such as In the Round: Portraits by Women Sculptors (New Zealand Portrait Gallery Te Pūkenga Whakaata, 2023) and Modern Women: Flight of Time (Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2024). Two of them, Alison Duff and Molly Macalister, appear to have followed Shurrock’s advice to “Take up some form of aesthetic expression, however simple and humble, where you can express your own self, not act as a medium for someone else.”10 In 1940, Duff worked with Chrystabel Aitken to create a thirty-metre-wide bas-relief frieze for the New Zealand Centennial Exhibition in Wellington. Her artistic career lasted more than sixty years and was characterised by a fascination with New Zealand’s plants and animals and the desire to see them protected. She embraced whichever new materials and techniques would allow her to most closely express the essence of her subjects, often including acoustic elements in her carved and welded depictions of pīwakawaka, kōtare and tūī. In 1963, she was commissioned by the Arts Advisory Council to make a bronze bust of the writer Frank Sargeson, who was also a friend. Duff’s much-loved sculpture combines a lively surface with a dynamic pose, vividly capturing the charismatic author in story-telling mode. Sargeson later admitted that she had produced a torso so good that he was obliged to admire it even more than himself.

Molly Macalister described Shurrock as a dynamic and inspiring teacher. Born in Invercargill, Macalister soon showed promise as a carver, working in both wood and limestone. After two years at the art school, she undertook war work in 1940 as a land girl in Southland and then worked at the Otago Museum, making animals for agricultural displays. In her later work, she specialised in human figures and animals, creating a number of significant public sculptures that are distinguished by their power, presence and strong sense of internal life. Her bronze in Auckland’s Queen Street, A Māori Figure in a Kaitaka Cloak (1967), was the first public sculpture by a woman commissioned in New Zealand and her cast cement figure Bird Watcher (1961) became a favourite of many. One version of it caught the eye of Macalister’s friend Colin McCahon, who happily agreed to exchange it for one of his Kauri paintings. Like Duff, who she worked and exhibited with, Macalister often used concrete, cast or built-up over armatures, as a sculptural medium, enjoying its immediacy and modernity.

The works of these two Shurrie-trained artists now provide inspiration for a new generation of sculptors interested in materiality and self-expression – a fitting continuation of his impact on their own careers. For while he insisted that his students must learn the skills of their trade, and that their works must be well made (he once stated that a sculpture should be capable of being rolled down a hill without damage),11 perhaps his most lasting invocation to those wishing to make art was this: “be alive to the revelation of beauty in the most unexpected places.”12