Practice, Poetry and Precision

A new site-specific sculpture for Te Puna o Waiwhetū

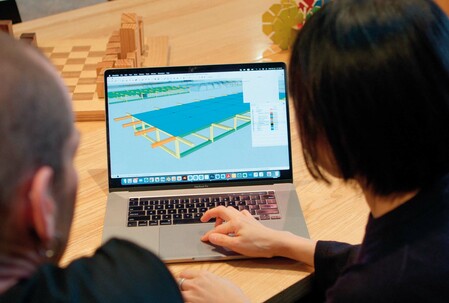

Yona Lee at work in her Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland studio in 2024. Photo: Belmont Productions Ltd.

Artist Yona Lee has been preparing something very special in her Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland studio – a new commission that honours the history of the Gallery building, Te Puna o Waiwhetū. Lee took some time away from her workbench to speak with lead curator Felicity Milburn about her dream of filling the under-stairs space with water and light.

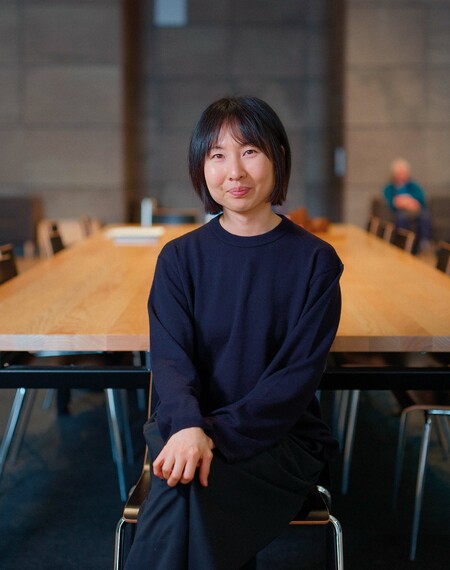

Yona Lee at Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū in 2024. Photo: Belmont Productions Ltd.

Felicity Milburn: Yona, you visited Te Puna o Waiwhetū on a very wet day last year to consider possible locations for the commission and begin developing your concept. Did you have any preconceptions about the building before this visit? What sorts of things were you thinking about during the day, and what ideas did you take away with you?

Yona Lee: I had been to the Gallery before, and my memories of the building were to do with the grand glass style that is so particular to the Gallery. But I remember trying to be really open minded because the invitation was very open. My focus was on trying to read the space and ask lots of questions about the history of the building. Because the commission is a gift to celebrate the building’s twentieth birthday, I felt it was especially important to be mindful of the wider context and the Ōtautahi Christchurch com- munity as well as the building.

FM: Were you also watching how people used the space?

YL: Yes, I was really interested in how people used the site in the Gallery, and the fact that there’s no single entry point to the building. I was quite fascinated by the multiple entrances. There are a lot of hierarchies that exist in the building, such as the grand marble staircase that divides the left and right sides. There’s the dramatic glass façade, but then the east side of the building around the car park area is quite bland. Something about those contrasting qualities really stood out for me. I tried to read the architects’ intentions. For example, they took the outside bluestone bricks and used them in the interior as well. There’s something there about really highlighting the transparency of the glass façade and the transition between inside and outside. The experience of entering the space felt so natural, it wasn’t like, “Oh, I’m entering the museum”, it was more like suddenly “I’m inside”. There’s a blurring of boundaries that is quite special, and I think it helps bring people into the Gallery more easily. I was also mindful of the existing works in the foyer by Bill Culbert and the Mataaho collective. They’re hung from the ceiling, so I was thinking about the grand gestures of these existing works as well as the architectural features of the Gallery, and whether I work with them or oppose them with something different. I think I began to search for spaces that were disguised or hidden and not really activated, and then the underneath of the staircase really came to mind. It was important to me that the work operate at a human scale, so that it acts as a mediator between the architecture and the audience.

Yona Lee at Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū in 2024. Photo: Belmont Productions Ltd.

Yona Lee at Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū in 2024. Photo: Belmont Productions Ltd.

FM: As you mentioned, this commission celebrates the twentieth anniversary of the Gallery building. How did that affect your concept?

YL: When you think about giving a gift to someone, the first thing you think about is who that person is – what they need or what they like. I really wanted to make work in the spirit of giving and celebration, and I wanted to think about that in relation to the history and the context of the building. These things came together quite slowly. I think the building has got everything, it’s quite incredible to think about the repairs that have been done and the base isolators – everything is so prepared. It’s got those amazing Culbert and Mataaho installations. I thought, “What are they missing? What else do they need?” And then, while I was asking questions about the building, I learned that it used to have ponds in the floor, inside and outside. You can clearly see how important it was to reference water and the Ōtākaro Avon River in the architecture and design, including the wavy façade. So it was interesting to discover that they also originally emphasised that even more with real water. I learned that these ponds created a safety issue because people tripped over them, and also that a pair of ducks were coming under the façade into the Gallery through them. I thought that last part was quite funny. Because of these factors, the ponds were removed. I thought about how the water was given to the community but taken away, and, maybe, that’s some- thing I want to give back – to restore it in a different way.

I was also thinking about the Māori name that was gifted to the Gallery, Te Puna o Waiwhetū, in reference to the artesian water that flows beneath it and into the Ōtākaro, the ‘water in which stars are reflected’. I thought that was just so beautiful and poetic, it made me imagine the life-giving property of a spring, flowing through the Gallery to the com- munity. I think that is the true role of a museum – giving back to the community.

I also thought about the fact that some of the original pools had been replaced by a big table with books and puzzles, making it a place for people to rest and socialise. I wanted to respect that part of the space, and to utilise it in a way that would also bring the community together. That led to the decision to include a bench, with tables and shelves, back in that place. For me, that under-stairs space is really important because it’s a transitional space – you have to walk past it to enter the exhibition spaces, so there’s an opportunity to enhance the experience of the exhibitions. I’m hoping the work might let it function as the heart of the space, where people can come back to rest. I think the water has meditative properties that will help with that.

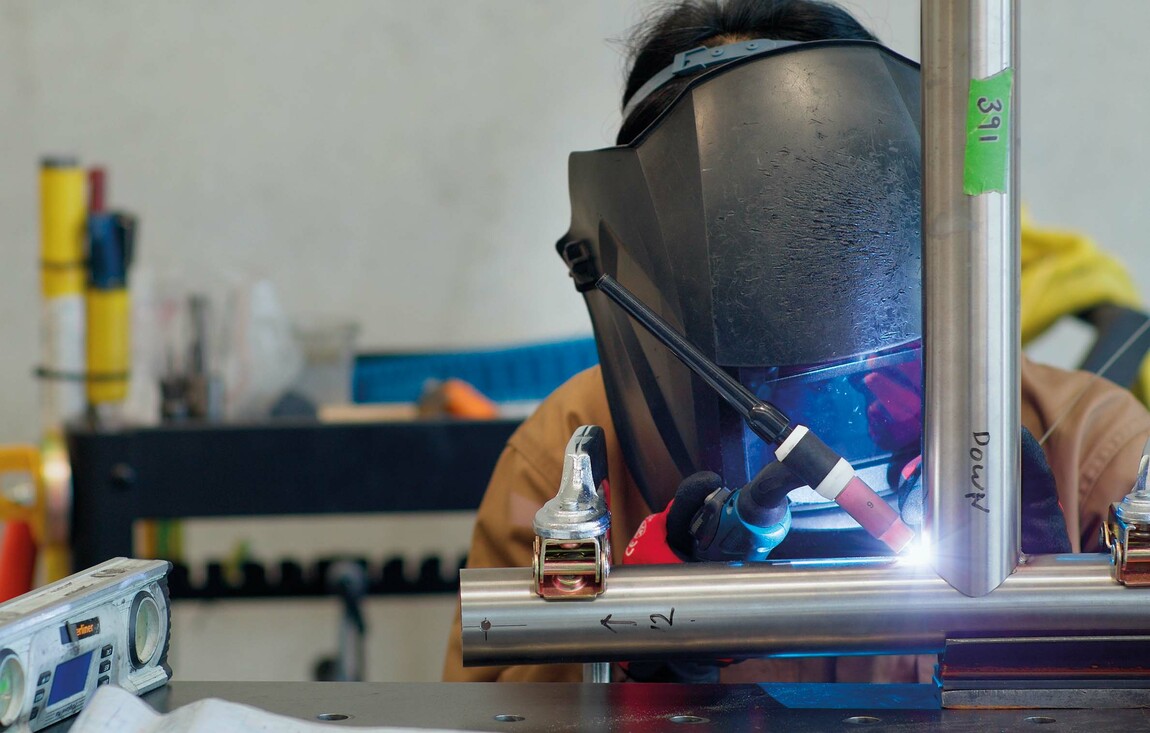

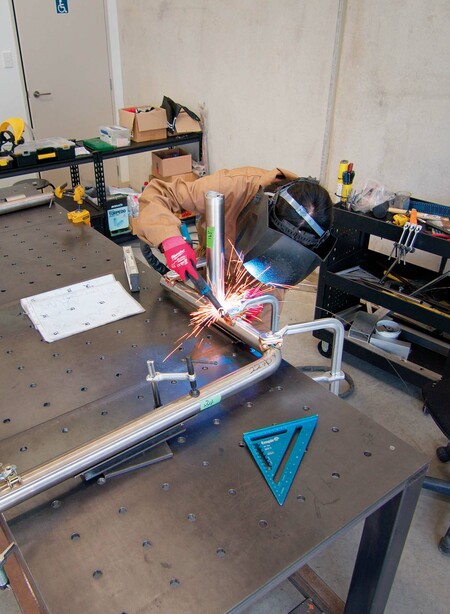

Yona Lee at work in her Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland studio in 2024. Photo: Belmont Productions Ltd.

Yona Lee at work in her Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland studio in 2024. Photo: Belmont Productions Ltd.

FM: In a public space, water can be a focus for collective experiences and social connection, as with a civic fountain. But the found objects you have used suggest a more domestic setting. What sorts of associations were you interested in drawing out with this work?

YL: Yes, it includes some objects that we find in public spaces, like street lights and fountain nozzles. I think of those aspects as being like the bluestone that is used outside on the forecourt, but also inside. It helps to bring the street elements into the Gallery and of course the stone pools allowed the water to be present. If the flooring was precious wood, I wouldn’t be able to use water, so lots of elements in the space helped provide this language. There’s also definitely an emphasis on utilising domestic objects like tapware, and I was thinking a lot about the daily encounters we have with water: we drink, we wash dishes, take a shower, wash ourselves. These daily activities are repetitive and very close to us. It’s interesting to think about how the nature of our relationship with water depends on which nozzles or objects it flows through. They carry the essence of different spaces and functions. We categorise them: water through a kitchen sink is to wash dishes with; water flowing through a drinking fountain, we know that’s for drinking; the basin mixer is for hand and face washing; and the shower head provides water to wash our bodies with. But they’re all connected. I was interested in this water – not the sea or the rain, but the water that’s so very close to us. Some of these encounters are very personal, very intimate, and I was thinking about how we are so vulnerable, say in a shower context, you know? So for me, by using these objects, I hope to evoke these kinds of personal, intimate experiences and memories of water in the audience, while they’re in a very public setting. I’m hoping to connect more deeply, on a more personal level, and prompt thoughts about how we act differently in private and personal spaces. The difference is necessary, but thinking about those gaps is sometimes very interesting.

FM: I’ve been thinking about how the moving water will bring in a sound element – is that also important to the work?

YL: Yes, the sound will be a bit more subtle than the usual public fountains we encounter, but it will extend those ideas around the impact that water has on us. There are lots of studies demonstrating that the sound of water provides therapeutic benefits and is a form of white noise that is very stress reducing. The immateriality of the sound is quite important sculpturally because it acts as a counterpoint to the solidity of the metal structure. Coupled with the light elements, the movement and continuous flow of water somehow makes the structure feel alive. And because you can see the water flow, and hear the sounds of it moving through the taps and nozzles, that makes you aware that the structure is hollow; even though you can’t really see it, you can imagine the movement happening inside the pipe.

Yona Lee at work in her Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland studio in 2024. Photo: Belmont Productions Ltd.

FM: People have compared your work to music, referencing your early training as a cellist. It’s possible to make those connections in this work – the combination of complexity and simplicity, formality punctuated by more organic notes and alternating rhythms and textures. Do music and sculpture have much in common for you?

YL: I think those sorts of readings of the work in relation to rhythm just work themselves in naturally, I don’t necessarily think about it when I am making the work. I think it’s more about how the act of practicing for performance affects my thinking about space, the process and the material. For me, the connection is in spatial articulation through linearity, whether that be notes played through the act of bowing the cello or in the tubular structures. I think it’s probably to do with the journey one takes in active listening and following. On a stringed instrument there is a relationship between thickness and strength – the thicker the string is the lower the pitch it produces. That’s very similar to tubing because, depending on its thickness, its strength and its relationship to objects and our body changes. Thicker tubular structures are stronger, and they become more architectural. Making lines vertical, plum and level isn’t straightforward because the material is very sensitive to heat. I find the process of getting it right very similar to finding the right notes on a string. It’s not like a piano, when everything is precisely tuned where you hit the note. On a stringed instrument, you have to find the notes and there’s always an element of compromise – you can go slightly flat or slightly sharp. For me, that process is really very similar to levelling the structures, and once you get them right it’s very satisfying.

FM: And do you immediately recognise it when it is right?

YL: Yeah. I treat it like when I used to learn a piece of music by a composer. You try to follow every instruction that’s written, or passed on, but sometimes they’re from 100 years ago. Even with very contemporary pieces you try to read and follow all the instructions, where you should be quiet and where you should be loud, the tempo of the piece, the mood, where the rest points are. You try to follow the instructions as closely as possible, but I think the magic is in the performance, when the performer can interpret the piece and bring their own voice to it. Even though hundreds of different performers follow the same instructions, there’s a beauty in somehow making the music yours. I think I bring the same approach to working with spaces – each space holds so much information already, it has hidden and clear intentions. I think it’s a mistake to try to ignore all of that and consider everything as neutral. I try to read every detail of the space, and then to interpret that space in my own voice, emphasising places that I think are important.

FM: It has been fascinating to watch this work develop from the initial conceptual drawings through to plans that are more detailed and technical. I imagine that the materials and your sculptural approach require you to be quite systematic. Do you enjoy that aspect?

YL: The systems I’ve been developing have helped me to take on large-scale projects while still keeping a lightness to the work. Large sculptural works have often, historically, been associated with male sculptors. But my work is not about having big muscles, it’s about the system. The system allows the work to exist. Yes, the process can be very long and laborious, depending on the scale, but the idea of realising the project excites me and that helps me carry the process through. In performance, I remember my tutor used to tell me, “When you play a piece of music, it’s important to perform in one breath.” I think she meant something like keeping that momentum, keeping the right amount of tension. That process feels, to me, quite similar. I remember listening to an interview with the architect Frank Gehry, who talked about how in architecture it takes years to plan and make and finish the building. The process is very systematic, it’s long and not very exciting, but he said that the magic lies at the end of that long process, when you still feel the building contains a sense of improvisation. That’s the thing that lets you carry it through that laborious process.