Spring Time is Heart-break

Contemporary Art in Aotearoa

Ilish Thomas Indira’s Birthday (ઇન્દિરાનો જન્મદિવસ) (still) 2022. HD video; duration 8 mins 3 secs. Courtesy of the artist

Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū’s new exhibition Spring Time is Heart-break: Contemporary Art in Aotearoa takes its title from one of six poems written as memorials by Ursula Bethell after the death of her partner Effie Pollen. The couple’s relationship mirrored the seasonal changes in the garden they tended together during the decade that Bethell was writing poetry on Ngā Kohatu Whakarakaraka o Tamatea Pōkai Whenua, the Port Hills overlooking Ōtautahi Christchurch. For the poet, signs of spring became a bittersweet reminder of her lost love. Reading Bethell’s work today, her evocation of intense feelings and embeddedness with the land not only reflects the ethos of our present time, but also resonates with many of the works in the exhibition. Bethell claims that we are kin with the environment, foreshadowing ideas of human/non-human interconnectedness and echoing tangata whenua understandings of whakapapa to the whenua. Artist Aliyah Winter brought Bethell to our attention while she was conducting research for a new work; our choice of title was made to encompass seasons, temporality and emotion, as might be applied to contemporary practice in Aotearoa.

The loved little bird is singing his small song,

Dearest, and whether the trill of the riro

Reminded, we wondered, of joy or of sorrow –

Now I am taught it is tears, it is tears that to spring time belong.October 1935, Ursula Bethell

The twenty-four artists that we have included in Spring Time is Heart-break each have their own concerns and methodologies, yet gathered together they provide us with a snapshot of our current moment and the issues we face. There are tender stories relating to personal and collective histories; reflections on communication, correspondence and archives; observations of everydayness; perspectives that situate us with the sun, water, birds and land of Aotearoa; as well as journeys of translation from one place to another, across materials, times and languages. There is a return to storytelling, shared through the materiality, marks, sound and texture of the works, and the deliberate use of embodied knowledge and affect.

Grounding us in Waitaha, Te Waipounamu, Megan Brady (Kāi Tahu, Ngāi Tūāhuriri, Pākehā) has made a series of carpets, Entangled and turning, we are river, that materialise the flow of whakapapa, rivers and stories through topographical mapping of the braided rivers that are characteristic of this rohe. Having recently reconnected with her personal affiliations to Ngāi Tūāhuriri and the Rakahuri awa, Brady creates a space to contemplate our relationships with rivers and how these might define or reflect our identity.

Sound is used as a material across many works in the exhibition. Steven Junil Park and John Harris have developed a large amplifier that visitors can sit within; Abigail Aroha Jensen (Ngāti Porou, Ngāi Tāmanuhiri) considers the absence of sound as sound itself and the oro (sound) created within the rhythm of rope making. The sensory nature of sound carries us to emotional narrative content and cultural references, an undercurrent that runs through both the exhibition and contemporary practice today.

Ecological kinship and Kāitahutaka are at the heart of Madison Kelly’s (Kāi Tahu, Kāti Māmoe, Pākehā) practice. For Tohu! Karaka! Braid! Kelly plays field recordings of captive-bred kakī (black stilt) chicks being introduced to wild birds in their wetland habitat as part of the Mackenzie Basin’s Kakī Recovery Programme. The birds’ calls sound from behind a large mesh drawing, and Kelly invites us to respond to them with a percussive glass sculpture, using sound and interactivity to reinforce that our voice and participation are required if we are to care for taoka species and the environment.

Call and response as both a form of communication and way of locating ourselves can also be seen in the work of Luke Shaw. Learning that his grandparents communicated using small offcuts of steel and a mirror, flashing Morse code signals between their home in Aranui and Te Heru-o- Kahukura Sugarloaf hill when his grandfather was working on the radio transmission tower in the 1960s, Shaw had an analogue reverb plate constructed from steel. Into this he plays his version of the story, translated into Morse code and then treated as a musical composition (words as notes, tempo elongated into sustained drones) enabling an estimation of the familial anecdote to reverberate in the space. SUN TURN (Sugarloaf towards Lyndhurst) is an echo – distorted, transformed and atmospheric – that opens a portal through time to the sweet nothings the couple likely exchanged; an act of listening in on the past.

Private languages and histories continue in the work of Aliyah Winter, who drew inspiration from Bethell’s poem Weathered Rocks (1936) for her infrared video work Rock, thorn, cryptogram. A cryptogram is a puzzle, a way of making something visible only for those who can decipher the code. A cryptogam, however, is a plant or organism that reproduces by spores, without flowers or seeds. It has been pointed out that perhaps “Rock, thorn, cryptogam” is a more fitting combination as cryptogam is more relevant to both rock and thorn.1 Bethell was subtle about her sexuality and, read in conjunction with her poems, this sort of wordplay allows us to draw our own conclusions about her relationship with Pollen and queer history. Using a limited part of the electromagnetic spectrum, Winter has filmed herself in a volcanic landscape to expand on multilayered narratives for body and land.

Several other works in the exhibition take personal correspondence, letters and archives as a point of departure. The basis for Ilish Thomas’s video NAMASKAR & Merry Xmas is a letter from her grandfather, Raman Chhiba, recording his wishes for the family, which slowly scrolls upwards as it is read aloud by the artist’s mother. While the letter details financial matters and the distribution of property, it is incredibly moving and creates an intergenerational family portrait of South Asian diaspora. Alongside this, a second video, Indira’s Birthday (ઇન્દિરાનો જન્મદિવસ), captures Thomas’s mother putting on a saree for her birthday celebration. Textiles are an ongoing aspect of the artist’s practice and, in addition to the fabric in the video, Thomas divides the gallery space using a domestic lace curtain. The etymology of the term textile is related to both texture and to text, and identifies a fundamental relationship of the textile to language:

The plural of the Text depends … not on the ambiguity of its contents but on what might be called the stereographic plurality of its weave of signifiers (etymologically, the text is a tissue, a woven fabric) … woven entirely with citations, references, echoes, cultural languages (what language is not?), antecedent or contemporary, which cut across it through and through in a vast stereophony.2

Thomas brings text and textile to the fore, highlighting how families and stories are woven together, like threads knitted to form the structure of a cloth that is then wrapped around the body.

Sriwhana Spong Badlands (still) 2023. 16mm film transferred to HD video.

Courtesy of the artist and Michael Lett, Auckland

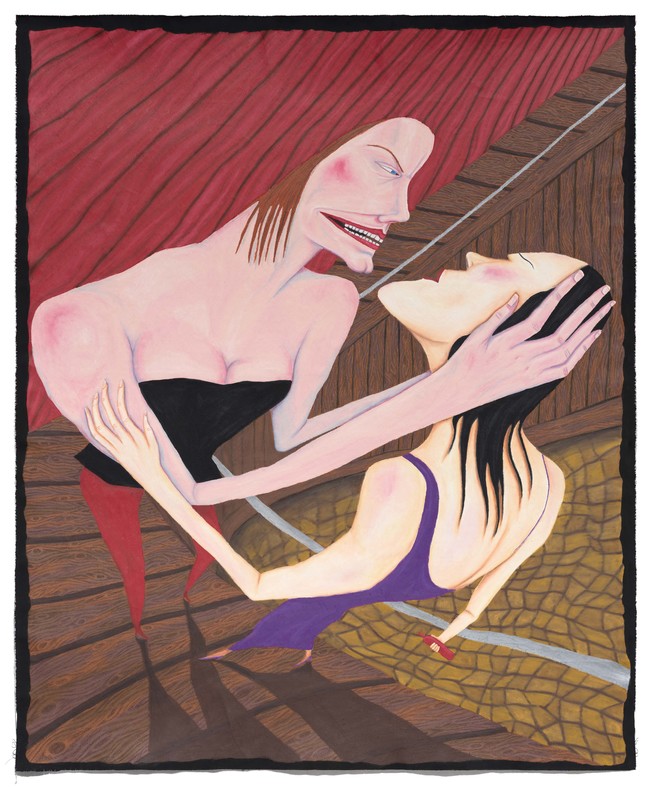

The long history of using ‘unmeasured ribbons’ for ritual magic in the South of Italy underpins a new 16mm film from Sriwhana Spong. While on a research residency in Siena, Italy, Spong became interested in the writings of anthropologist and philosopher Ernesto de Martino (1908–1965), in particular his book on Italian tarantism, The Land of Remorse (1961). In the ritual of the tarantella, the resolution of a per- sonal crisis occurs through colour, music and dance. Spong’s evocative work treats film as a medium through which choreography, sound and colour might produce a somatic effect in the viewer.

The paintings of Anoushka Akel similarly employ a specific reference from Italy – the drawing Asdrubale Bitten by a Crawfish (c. 1554) by Renaissance artist Sofonisba Anguissola. This work is known for the depth of emotion that Anguissola was able to achieve, and the way that it inspired Baroque painter Caravaggio. Akel is interested in gestures that can be used to convey affect for her new body of work Click Hiss Rasp Howl, as well as the interrelationship of species. Her title lists the vocabulary of sounds that kōura, freshwater crayfish, use to communicate with each other; kōura are uniquely blue in Te Waipounamu, a particular hue that recurs in Akel’s work. Awash with marks and tones that hint at recognisable forms, the works remain exquisitely fluid and full of abstracted texture.

For Wai Ata Āta Whāia, Heidi Brickell (Te Hika o Papauma, Rangitāne, Ngāi Tara, Ngāti Kahungunu, Rongomaiwahine, Ngāti Apakura, Airihi, Kōtarani, Tiamana, Ingarihi) collected rimurapa (bull kelp) that had washed ashore, working with the organic shapes of the seaweed to create elegant coils. They spiral from rākau (wood) wound with dyed cotton twine, a deconstructed form of painting or drawing in space. Through this process of connecting with the moana, Brickell acknowledges Tangaroa, the atua of the sea, lakes, rivers and all the creatures which live in them, and who is also gifted with the art of carving. In looking to the moana, Brickell is also thinking about the waves, weather, our relationships to water, and the internal feelings that echo and respond to the environment. She writes:

My practice, through materials, through relationships and through the reo, is a wānanga that pursues vital indigeneity, exploring roots and journeys, and letting seeds from those journeys flourish within the soil, or the ocean, of the hinengaro. The intimacy with this whenua reflected in our language and stories builds on thousands of years of living on the ocean, and I’m particularly interested in how its qualities and the technologies used to exist with it, now inform the reo we have to express ngā kare ā-roto, or, our emotional experiences of the world around us.3

Anoushka Akel Moral Messaging 2023. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of the artist and Michael Lett, Auckland. Image courtesy of Sam Hartnett

While many of the artists have incorporated historical references, there are meditations on the present moment and everyday life too. Angel C. Fitzgerald presents a video based essentially around friendship, a beautiful compilation of moments from life edited to a score. In Nowhere, Campbell Patterson has compiled a series of self-help suggestions handwritten on masking tape: from taking vitamins and paracetamol to eating vegetables, not biting fingernails and checking the mailbox. There is an underlying anxiety, or vulnerability, in these notes, as well as humour.

The selection of works I have described gives a sense of the tenderness that is present throughout the exhibition, the recurring moments of feeling, emotion and affect. Though Spring Time is Heart-break may at first seem to dwell in sadness or poignancy, it also invites us to consider cyclical forms, rebirth and the future. As political theorist Brian Massumi claims, affect opens up the potential for hope:

I use the concept of ‘affect’ as a way of talking about the margin of manoeuvrability, the ‘where we might be able to go and what we might be able to do’ in every present situation. I guess ‘affect’ is the word I use for ‘hope’. One of the reasons it’s such an important concept for me is because it explains why focusing on the next experimental step rather than the big utopian picture isn’t really settling for less.4

Taking this view towards the affective element of works, Etanah Lalau-Talapā’s meditative 3D digital work Loto fa'afetai, loto fa'atuatua (2021) reinforces the dual emotions of grief and celebration, while Priscilla Rose Howe proposes a vibrant queer vision of the future.

Priscilla Rose Howe Different versions, different bodies, different words 2023. Flashe, acrylic and oil pastel on canvas. Courtesy of the artist and Jhana Millers Gallery, Wellington

Returning to the garden, in Juliet Carpenter’s compelling black and white film The Sun Is Not To Be Believed, a shrouded figure digs in the earth of an allotment. Combining references to Maya Deren’s avant-garde film Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) and the logic of Samuel Beckett’s Quad, written in 1981 for four performers who appear to exist in parallel time spaces, Carpenter’s work is driven by a computer algorithm that decides the edits and image overlays as the video sequence repeats four times. Each permutation brings in fragments from both the future and the past to create a temporal fissure, casting the sun as an unreliable timekeeper, and our perception as inconsistent.

The sun and weather patterns loom over many works in the exhibition, just as they do in our daily lives, and while not explicitly referencing climate change, artists are addressing atmospheric conditions, the soil, rivers and oceans that are part of us. Spring Time is Heart-break asks us to engage in meaningful experiences with each other and the world around us; digging, listening, observing and communicating across time, place and species.