Something’s Missing

The Power of Absence

![Petrus van der Velden Burial in the winter on the island of Marken [The Dutch Funeral] (detail) 1872. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of Henry Charles Drury van Asch, 1932](/media/cache/eb/a3/eba3be2198fcc7cf03af09ae8196c7b1.jpg)

Petrus van der Velden Burial in the winter on the island of Marken [The Dutch Funeral] (detail) 1872. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of Henry Charles Drury van Asch, 1932

It’s among the best-loved paintings in the Gallery’s collection, celebrated for the connections and conversations it generates between different generations. People who, as children, encountered Petrus van der Velden’s Burial in the winter on the island of Marken [The Dutch Funeral] (1872) in the neoclassical spaces of the old Robert McDougall Art Gallery now bring their own grandchildren to Te Puna o Waiwhetū to see it.

Robin White Saying goodbye to Florence: Te Puke: time to go 1988. Relief print. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1989

They study the faces in the mourners’ procession: the stoic men who wrestle the sled through snow spiked with half-buried plant stalks; the woman just behind them, folded over by grief and supported by her companions; the young children – respectful, but taking it all in. While looking, viewers may register how countless small artistic choices create a powerful sense of emotion and place; how the red noses, snow-dusted shoes and hunched shoulders convey both ankle-shattering cold and numbing loss. Van der Velden’s painting is a work full of meaning and emotion, but it contains one conspicuous omission. The central figure, whose death has prompted everything the artist shows us, is invisible, present only through the darkest shape on the canvas, a shrouded coffin bound with ropes. The body itself – as expected – is unseen, but the missing person (said to be a drowned local fisherman) remains central to the story, hovering persistently at the edge of perception.

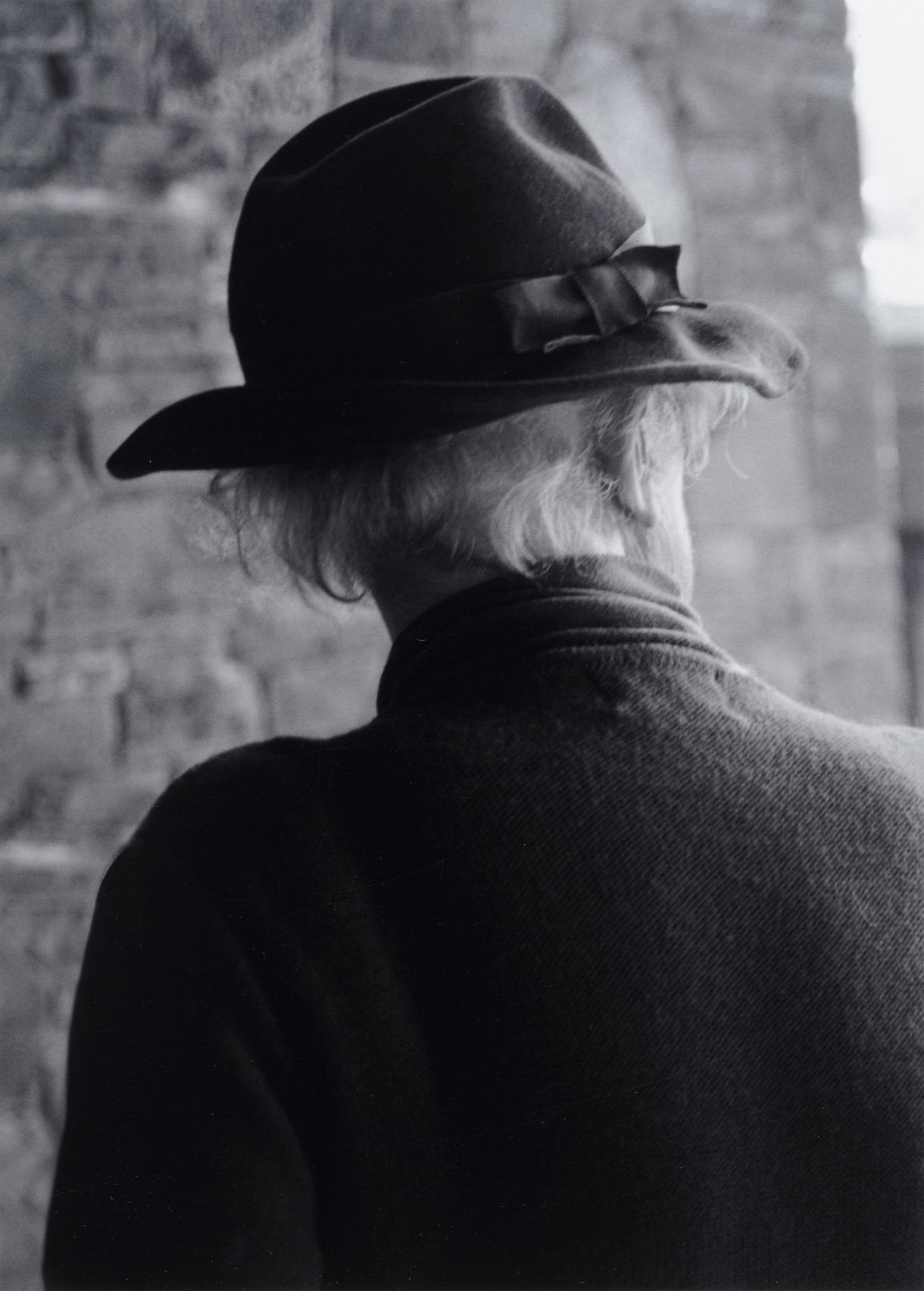

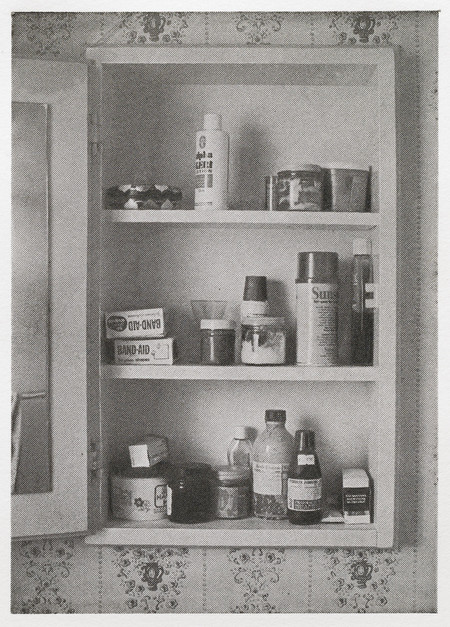

The power of people and things not shown has always fascinated me, as it has fascinated many artists. In art, absence creates mystery, tension and anticipation, implying loss, transformation, exclusion, isolation and much more. It is the unspoken subject in some of the Gallery’s most interesting works. Absence, of course, is connected strongly with death, and works of this kind often carry an elegiac quality. In many of Robin White’s works, landscapes, vehicles and roadside buildings seem poised, as though waiting for someone to arrive, but absence is felt especially keenly in Saying goodbye to Florence (1988), a suite of twelve prints that marks the death of the artist’s mother. The first six works are embossed photo-etchings that began with photographs White took in Florence’s Te Puke home on Christmas Day, the morning after her funeral. They are subtitled Te Puke: time to go – the last phrase recalling how Florence would often sign off her letters. The rooms revealed in White’s images are intensely empty and bereft of a familiar, expected presence. Yet a strong sense of character emerges from the objects Florence left behind; the modest furniture, neatly arranged ornaments, and well- ordered bottles in her bathroom cabinet. Capturing these everyday details with a tender precision that resembles a ritual of farewell, White resurrects the fullness of a life that exists now only in memory. Later, White – then living on Tarawa atoll in the Republic of Kiribati – made a set of accompanying screenprints. Following an order determined by the ebbing tide, they showed the view across the lagoon towards Makin – a path the locals believed was taken by the spirits of their ancestors.

Käthe Kollwitz Tod Greift In Kinderschar 1934. Lithograph. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased with assistance from the Olive Stirrat Bequest, 1988

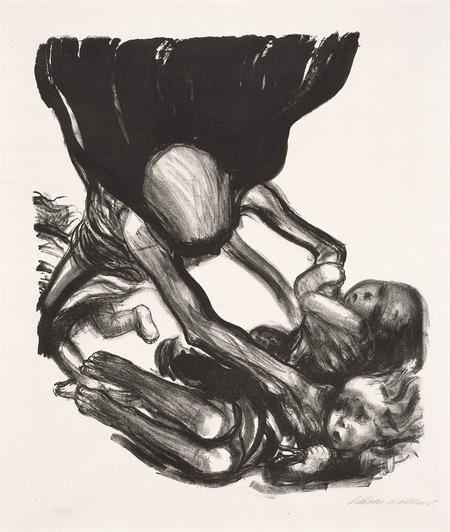

Loss of a more savage kind haunts the prints of mid twentieth century German artist Käthe Kollwitz. Raised in a progressive, non-conformist family, her early works were motivated by social injustice, and she documented the struggles of those living on the breadline. As Hitler’s Nazi Party began its rise to power, she turned her attention to the violence and horror of war. Kollwitz’s last series of lithographs, completed between 1934 and 1935, depict Death (Tod) as a cloaked figure, visiting a series of people. Some welcome him as a release from pain; others regard him with wide-eyed dread or dazed defeat. In Tod Greift In Kinderschar (1934), Death reaches into a group of children, his black shroud flying up behind him as his long fingers grasp their cringing bodies with a terrible urgency. Kollwitz, who witnessed suffering daily in the poorer streets of Berlin, was no stranger to grief. Her youngest son was killed in World War I and her grandson died on the Eastern Front in World War II. Hers is a dark and horrifying vision of life snatched away in front of our eyes.

Ben Cauchi Hovering Object 2005. Ambrotype. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2005

To those who viewed them, and perhaps to some of those who made them, the first photographs must have seemed like miracles or magic tricks. Photography soon developed a close association with both sleight of hand and the supernatural; at a time of genuine uncertainty about exactly what a camera could and couldn’t capture, ‘spirit photography’ became increasingly popular. Unscrupulous practitioners used effects such as double exposure to cash in on the desire to glimpse the paranormal, or the longing to reconnect with a lost loved one. Ben Cauchi’s photographs entice us back into this ambiguous territory, resurrecting the ambrotype, or wet-plate collodion positive process, within a contemporary frame of reference. In Hovering Object (2005), a strange shape or light appears to emerge from behind the cloth backdrop of a Victorian photographer’s studio. The scene vibrates with a strange, unsettling tension. As accustomed as our contemporary eyes may be to deciphering tricks of light and screen, there’s a persistent, ancient part of us that anticipates what might appear. “I’ve always been interested in ideas around absence and the before or after (the non decisive moment) and this idea of the space between actions,” Cauchi has said.1 Like a cartoonist leaving one frame bare, he opens up room for us to fill in the blanks, and the not-knowing tempts us to return for a longer look.

Installation view of Dane Mitchell: Unknown Affinities, Two Rooms, Auckland, 2022. Image courtesy of the artist and Two Rooms

Katharina Jaeger Pracht 2008. Textile and found object. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2008

Furniture is supposed to accommodate the human body, fitting itself around our comforts and needs. In Katharina Jaeger’s 2008 sculpture Pracht (loosely translated as ‘splendour’) however, the familiar turns subversive, taking on a strange and unpredictable life of its own. After coming across an assortment of discarded furniture parts in an Ōtautahi Christchurch junk shop, Jaeger felt “a desire to create something that leaves room for the thoughts of the viewer.”2 Pracht’s curved wooden legs, which in more usual circumstances would suggest elegance and stability, are poised to take flight, or perhaps to pounce. We can’t decipher what lies beneath the cloth that tops them, but there’s definitely something there, ready to move the moment you take your eye off it. Emanating what writer Andrew Paul Wood dubbed a “delicious creepiness”,3 Jaeger’s furniture is full of mystery and ominous tension, the polar opposite of cosy comfort.

Dane Mitchell’s art deals in elusive physicalities- scents that waft invisibly around a room, things lost, replaced or forgotten. His most recent body of work, Unknown Affinities, presented a museum of the absent – one in which the objects themselves had disappeared, leaving only the spare artefacts of their mounting mechanisms. One, bird of unknown affinities, Manu antiquus, acquired for the Gallery’s collection, recalls a species of extinct bird from Te Waipounamu. Dating from the Oligocene (part of the Paleogene Period, approximately 33.9 to 23 million years ago), its existence was established by the British zoologist Brian Marples in 1946 from a fossilised fragment of wishbone found near Duntroon in Otago. Researchers have speculated that it may have been an early albatross or a pelagornithid-a prehistoric ‘false-toothed’ seabird-but perilously little is known for certain. Even its scientific name is vague to the point of obscurity: the genus name Manu is te reo Māori for ‘bird’, and antiquus the Latin for ‘old’ or ‘ancient’. This almost impossibly fragile hold on existence is emphasised in the slim, insufficient remnants of Mitchell’s sculpture. As humans teeter on the edge of further mass extinctions, what are we really looking at when we stand in front of a taxidermied bird in a museum, perhaps the last known individual of a species, destroyed to preserve it for posterity. What does it mean for an artist to make a work about this, and for that sculpture itself to then be preserved within a gallery’s collection?

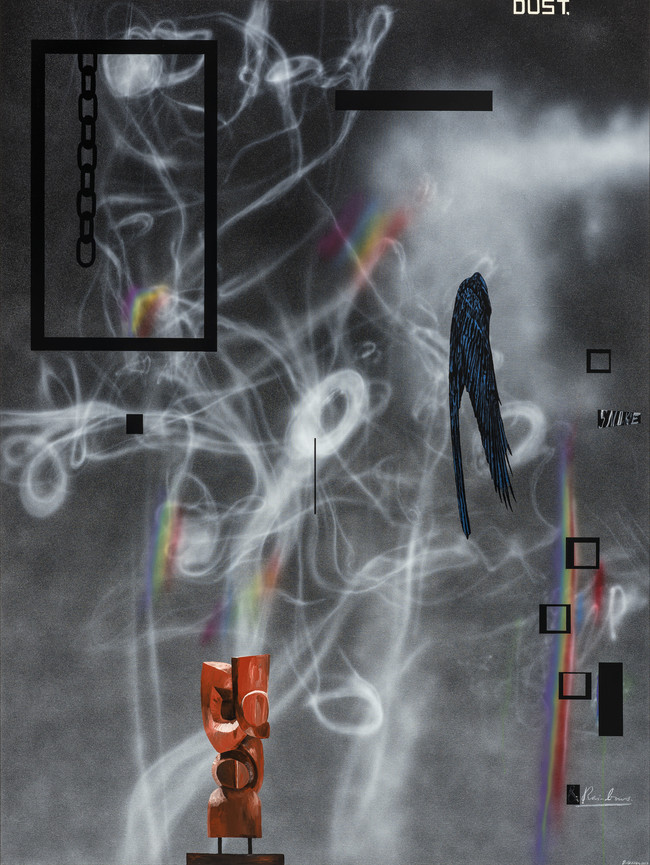

Shane Cotton Dust, Smoke and Rainbows 2013. Acrylic on linen. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of the artist, 2013

Claudia Kogachi Ghost 2022. Acrylic on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2022

Te Ao Māori and the cosmological concept of Te Kore offer us another way to understand absence. Before Te Ao Mārama, the world of light, was Te Pō, the endless night; and before both was Te Kore, the void – a realm not of emptiness, but of potential. Shane Cotton’s Dust, Smoke and Rainbows (2013) crackles with a supernatural energy. Made following the 2010/11 earthquakes, it depicts a swirling in- between space, where the inheritance of the past mingles with the promise of the future, creating a new world that is charged with possibility.

For her 2022 exhibition, Heaven must be missing an angel, Japanese-born and Tāmaki Makaurau-based artist Claudia Kogachi presented her own endearingly idiosyncratic takes on a series of popular movies.

Replicating famous moments from films such as Brokeback Mountain, Kill Bill and The Fast and the Furious, she recast them with heroines from much closer to home-herself and her then-new partner, Josephine. One painting, recently acquired for the Gallery’s collection, recreates the much-parodied love scene from the 1990 American supernatural romance Ghost. Molly (played by Demi Moore) is interrupted at the pottery wheel by her husband Sam (Patrick Swayze), leading to a clay-strewn encounter accompanied by the swelling strains of the Righteous Brothers’ ‘Unchained Melody’. Later, Sam is murdered and returns home in ghost form, becoming frustrated by the difficulties of communicating across the physical/spiritual divide. With source material so deeply embedded in the collective pop-culture psyche – for a certain generation at least – Kogachi’s painting comes preloaded with the knowledge of what is to come. Calling up the original context with a few key details – the title, the pottery wheel, the positioning of the figures and the ceramics loading the shelves behind them – she engineers a change in personnel that disrupts the familiar narrative. In the original film, Molly and Sam fit comfortably within Hollywood’s acceptable romantic archetypes; they’re white, attractive, young and heterosexual.4 Kogachi’s unexpected substitutions underline how these narrow stereotypes can erase and invalidate other kinds of relationships – even as the films encourage us to imagine ourselves into the same situations as our favourite protagonists. Kogachi’s same-sex proxies may lack the hyper-real glamour of their Hollywood counterparts, yet they inhabit their roles with a surprising authenticity, as bound together by genuine feeling as van der Velden’s wintry mourners. Like wide-eyed innocents from a Piero della Francesca fresco launched unexpectedly into the future, they disregard our gaze and the parts they’re supposed to play, absorbed instead in the human reality of the here and now.