Cut It Out

Taking a Look at Aotearoa New Zealand’s Hand-made Modernist Prints

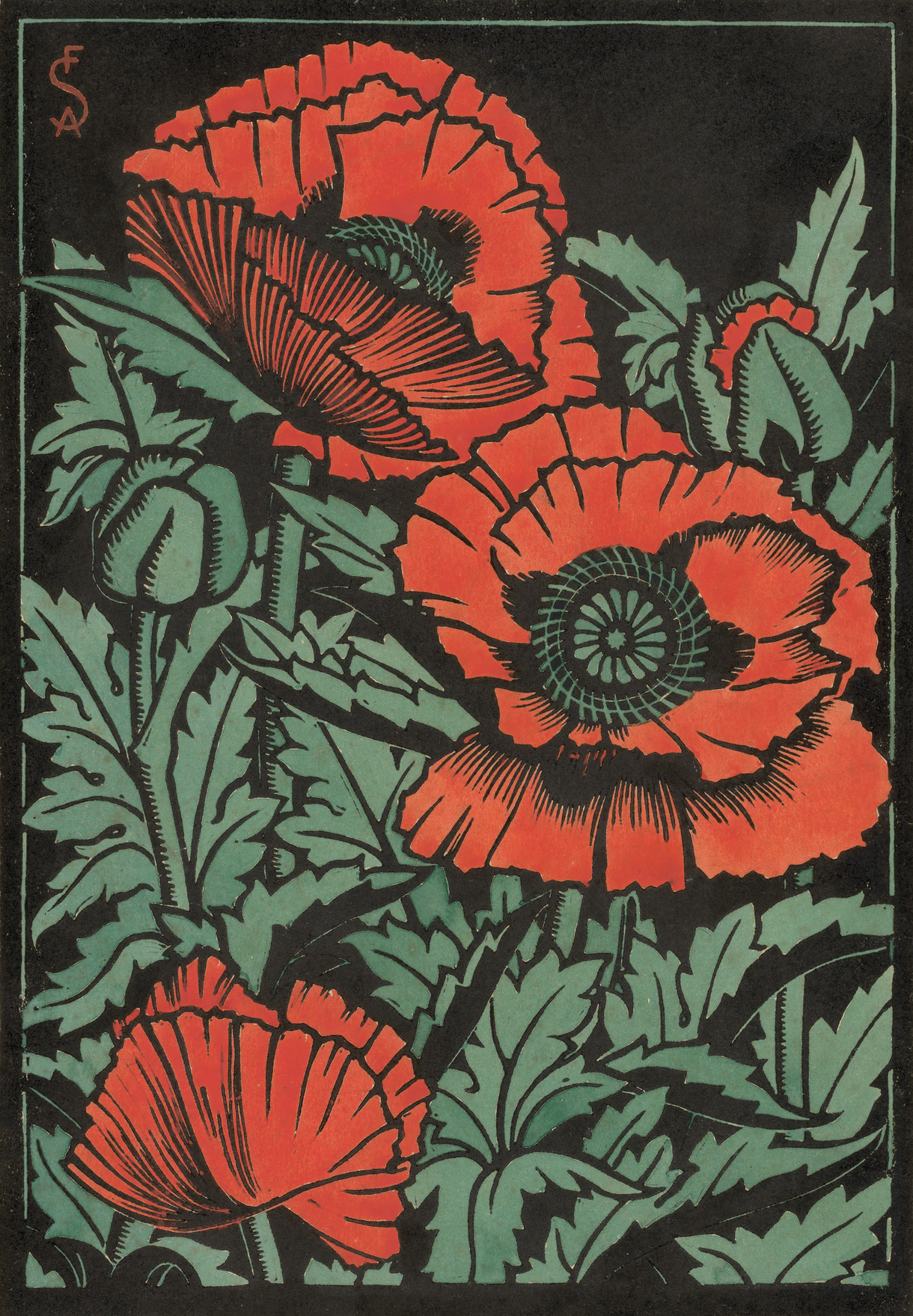

Francis A. Shurrock Poppies c. 1929. Linocut and watercolour. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2021

Make no bones about it, Ink on Paper: Aotearoa New Zealand Printmakers of the Modern Era is an exhibition I have long wanted to curate. I acquired my first print direct from Ralph Hotere when I was an art history student here in Christchurch many years ago. Hotere was the artist that piqued my interest in printmaking, but it is the Aotearoa New Zealand printmakers of the 1910s through to the 1950s that I love the most. Ink on Paper focuses on a generation of artists that were at the forefront of the medium when, following the printmaking revival in Britain, printmaking in Aotearoa was increasingly becoming accepted as an art form rather than simply a method of reproduction.

Works on paper conservator Eliza Penrose working on prints for the Ink on Paper exhibition, 2022

Ink on Paper includes examples of linocut, wood- cut, wood-engraving, lithography, etching (and even a humble potato print) by well-known artists such as Adele Younghusband, Rita Angus, Rhona Haszard, Doris Lusk and Colin McCahon alongside others that have fallen into obscurity like Marion Tylee, Harry Vye Miller, Gertrude Ball, Nancy Bolton and Frank Weitzel. Collectively however, as Marion Maguire says, “their artistic impulse shines through” and they laid the groundwork that subsequent generations of printmakers built upon.1 I love the roughness of many of the works in this exhibition and the linocuts in particular – a new medium for the new modern era of the 1920s and 1930s. The linocut encouraged simplification of form, and detail and imagery are often reduced to basic elements – solid masses of black and white rather than tonal gradations. The prints in Ink on Paper are, on the whole, small in size, subtle and intimate but ambitious. It is this that appeals so greatly to me – you have to get up close to experience the art.

I found the development of this exhibition highly rewarding, from taking stock of the Gallery’s collection of prints from this era, to ascertaining where the gaps were and figuring out how to fill them. Through purchase and gift we have added some stunning, and often rare, examples of printmaking by Rhona Haszard, Harry Vye Miller, Adele Younghusband, Gertrude Ball, Mabel Annesley, Leo Bensemann, Ivy Fife and Chrystabel Aitken to name a few. Some prints, such as Haszard’s Sidi Bishr, Egypt and Francis Shurrock’s Poppies, both coincidently linocuts made around 1929, were in a sorry state and required extensive conservation treatment by the Gallery’s works on paper conservator Eliza Penrose. I’d describe Sidi Bishr as being on life support when it first came into the Gallery but Eliza was up to the challenge and has done a remarkable job in saving this print. It is the only copy of this stunning work known to exist and was originally in the collection of Harry Vye Miller. Haszard studied in Christchurch at the Canterbury College School of Art and, after leaving for Europe in 1926 with her husband and fellow artist Leslie Greener, eventually settled in Alexandria, Egypt. While in London in 1929 the pair visited the First Exhibition of British Lino-Cuts organised by Claude Flight at the Redfern Gallery and were inspired to begin making linocuts. Back in Alexandria, they worked with the medium in earnest from October 1929 to March 1930, when the results were included in the exhibition Modern Woodcuts. It is a confusing title but the prints exhibited were all linocuts – the artists saw little distinction between these two similar types of relief prints. A short while later the pair contributed prints to the Second Exhibition of British Lino-Cuts at the Redfern Gallery alongside some of Britain’s most highly regarded printmakers, Claude Flight, Sybil Andrews and Cyril Power.

Francis Shurrock’s Poppies was also not in good shape when it was acquired as part of a larger grouping of the artist’s prints, photographs, sketchbooks, designs and sculptures. Given the rarity of this linocut, and the fact it was a unique version that had been hand-coloured with watercolours by the artist, it was also felt to be worthy of some much- needed conservation treatment by Eliza and rescued for future generations to enjoy. Shurrock was one of the young generation of progressive British artists who immigrated to New Zealand during the 1920s under the La Trobe Scheme, taking up teaching positions at art schools across the country in a bid to modernise attitudes towards art. Many of them, including Shurrock, Robert Field, William Allen and Roland Hipkins, had first-hand experience of the revival of printmaking that began in England in the 1910s, which they shared with their New Zealand students.

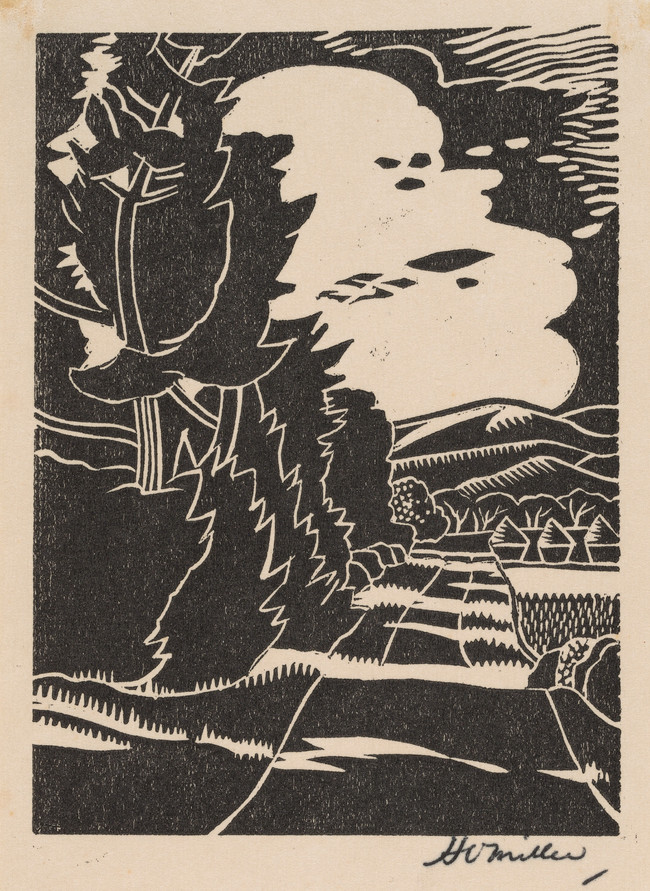

Harry Vye Miller Untitled c. 1931. Linocut. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2019

One young artist who benefitted immensely from the La Trobe Scheme was Harry Vye Miller. He studied under Field and Allen at the Dunedin Art School in the late 1920s and early 1930s, where Allen encouraged him in his printmaking. Miller’s family gave me access to a folio of his prints from this period, and it was an amazing experience to go through the unframed works. A selection was made to add to the Gallery’s collection and the story of this relatively little known artist and his intense interest in printmaking unfolded. Miller went on to become a champion of the linocut in New Zealand, producing numerous examples himself as well as taking up the artist/educator role. In 1942 he wrote the article ‘Teaching Linocutting’ for Art in New Zealand, in which he advocated the democratic nature of the medium and its suitability for its use by artists and art students alike, due to the fact that the materials used were very affordable and within anyone’s reach.

One of the least known yet most talented printmakers of her generation, Hinehauone Coralie Cameron produced wood-engravings and linocuts that were at the forefront of regionalism in New Zealand. Like so many of her contemporary artists she travelled to England in the late 1920s. There, she studied printmaking at the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London; her interest in modernism grew and she developed an appreciation for the avant-garde Vorticist movement under the tutelage of British artist William Roberts. Returning home to her family farm at Te Ore Ore in the Wairarapa, she continued her efforts as a printmaker, focusing on farm work, rural landscapes and wharves at Wellington harbour as well as modern Māori life at Te Ore Ore. Cameron was one of the few New Zealand artists to work as a wood-engraver during the 1930s, although her work was viewed as too modern by some and was refused for exhibition by the committee of the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts in 1937. Extant examples of her printmaking are extremely rare, which accounts for the relative obscurity of her profile as a printmaker – something I hope that Ink on Paper will rectify.

Juliet Peter Facades, W.9. 1954. Lithograph. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1954

In the 1950s lithography was taken up by several New Zealand artists including Juliet Peter, Louise Henderson and Colin McCahon. Peter in particular fully embraced the medium in her art practice. In England during the first half of the 1950s, she and her husband Roy Cowan studied lithography at London’s Central School of Arts and Crafts and the Hammersmith School of Arts and Crafts. Lithography was going through a revival at this time, with many contemporary British painters producing limited-edition original lithographs. The complicated printing process aside, lithography is a very natural medium for painters because it closely resembles painting in the use of washes and crayons. Peter found she had a natural and intuitive connection with it, although she wrote of finding its technical challenges “exasperating”. In 1954 she sent eight lithographs from London for inclusion in the annual Group Show here in Christchurch, and when she returned to New Zealand the following year she and Cowan brought with them a lithographic press, with which they continued to make prints from their studio in Wellington for several decades.

Although only a handful of artists are included in this article, Ink on Paper is the first extensive survey dedicated to printmaking from the Modern era. There is nothing ostentatious about the prints in the exhibition, yet together they are some of the most riveting works produced by New Zealand artists. Their impact is in the materiality of ink on paper, the duality of elegance and brutal simplicity, the skill required in their execution, and the personal scale on which they are made and viewed. These printmakers were at the forefront of modernism and the establishment of a New Zealand printmaking tradition, bringing the medium rightfully into the fold of respected creative practice alongside painting and sculpture, and contributing their own voices to a body of printmaking work we can all delight in.