The Golden Bearing and Postcritical Enchantment

Reuben Paterson The Golden Bearing 2014. Mixed media. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Bryan James, courtesy of the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery

Reuben Paterson’s The Golden Bearing is a life-sized tree in sparkling gold. This three-dimensional form extends the artist’s frequent use of glitter and diamond dust into the realm of sculpture. In doing so, his magical tree and its shimmering leaves speak to the complex and evolving relationship between nature and culture, via a grounding in hope, joy and wonder.

“The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing which stands in the way.”

William Blake

Paterson regularly explores notions of nature and light by incorporating glittering floral motifs that reference his Māori and Scottish ancestry. By here applying glitter to a deliberately archetypal tree form, Paterson invites an analysis of our diverse links to the environment in Aotearoa New Zealand. However, the shining golden colour of the tree also evokes a sacred and enchanted feeling that conjures up stories and myths about trees from a wide range of cultures.

One of the primary stories symbolised by the glimmering form of The Golden Bearing is the Māori creation myth regarding the separation of land and sky in order to let in the light, Te Ao Mārama. Paterson has used glitter to represent Māori concepts of light since his time at art school. However, this referencing of ancient legend can be extended in many directions and might also bring to mind European myths such as Romantic Arcadian mythology. Trees are a common subject in art, and in a range of works in the Gallery’s collection they function both emotively and critically, embodying different views of nature and culture over time – some with a hopeful tone, and others more sceptical in mood.

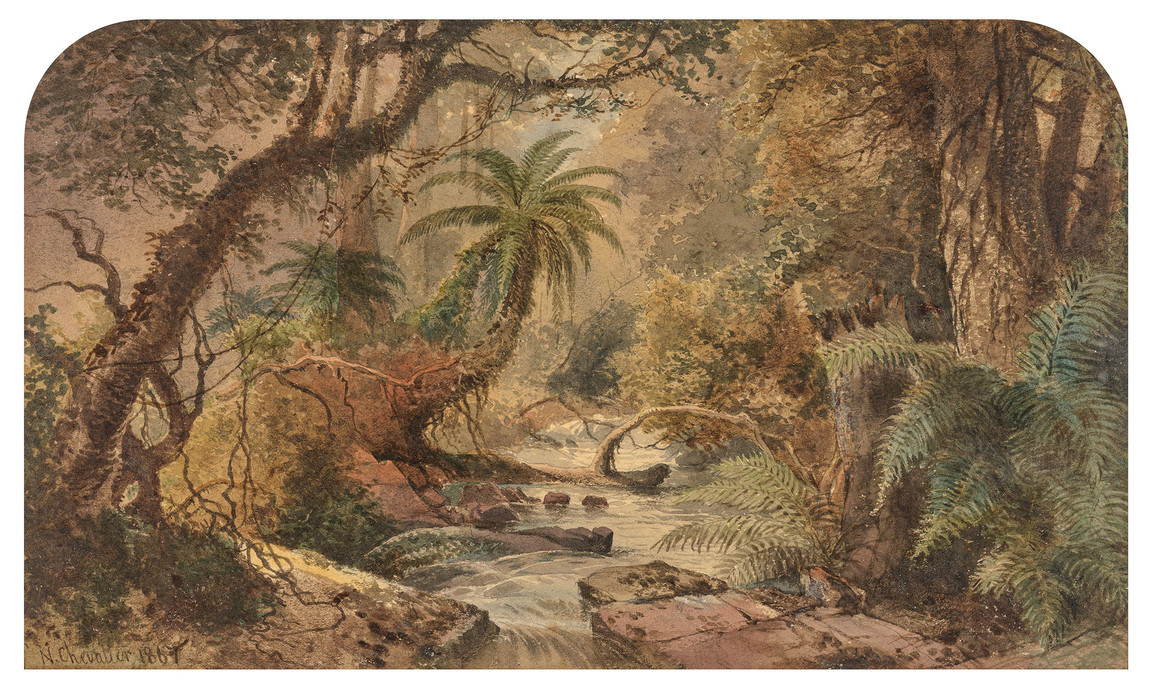

Nicholas Chevalier Pigeon Bay Creek, Banks Peninsula, N.Z. 1867. Watercolour. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2006

Petrus van der Velden Nor'western Sky 1890. Charcoal on paper. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of Jenny Wandl, Tricia Wood and Tim Lindley in honour of their grandfather, Harold Gladstone Bradley of Bradley Bros, Christchurch 2014

In two of the earlier works in the collection, Nicholas Chevalier’s Pigeon Bay Creek, Banks Peninsula, N.Z. (1867) and William Watkins’s View In Akaroa With Cattle (1879) Aotearoa’s trees are featured in the traditional European landscape form used by painters of the colonial era. Russian-born Chevalier travelled widely and his depiction of the New Zealand bush highlights its relative impenetrability when compared to European forests, with ferns, bracken and vines interlaced amongst the trees and alongside the stream. This idea of primeval forest is associated with the colonial view of lands like New Zealand as part of the ‘New World’, and in particular the now derided notion of the South Island as terra nullius. The Romantic idea of the enchanted wilderness sits neatly alongside the notion of the pastoral idyll that can be seen in Watkins’s painting of cattle calmly drinking from a stream and standing in the water to cool down on a warm day. The uprooted trees and surrounding foliage create a sort of stylised natural enclosure that shelters these gentle, introduced beasts from the elements.

A more ominous tenor is evident in Petrus van der Velden’s Nor’western Sky (1890). Here the trees on the skyline seem to be struggling against the wind, bashed about in the last light of the day. These trees can be seen as symbolic of the struggle of the colonial pioneer against nature – represented by the bent form of the woman occupied by her chore at the water’s edge. As opposed to a land of milk and honey, the realities of colonial life in Aotearoa often meant both a brutal battle against nature, and war with the indigenous Māori population. European men held almost all of the power in the process of artistic canonisation during the early colonial era, but works by women can increasingly be seen to form part of the collection as time progresses. Margaret Stoddart’s impressionistic flower painting of a pretty blossom tree next to the Avon River, Blossom, Worcester St Bridge (1928), and Eileen Mayo’s playful linocut of two cats in their leafy suburban jungle, Cats in the Trees (1931), both revel in the joys of the natural world.

Eileen Mayo Cats in the Trees 1931. Linocut. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, presented by Rex Nan Kivell, 1953

Louise Henderson Bush series No.7. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, Dame Louise Henderson collection, presented by the McKegg Family, 1999

And whilst Rita Angus’s post-war vision of hope A Goddess Of Mercy (1945–47) features tree branches that form a sort of halo for the serene goddess, hope can also be felt in her friend Juliet Peter’s painting Bolton Street, 1969 (1969); despite being set in the cemetery that the two women visited together to draw and paint, this artwork is far from bleak. Bright green foliage dominates this scene, offering a sense of regeneration and growth that smothers any gloom associated with the graveyard ruins. Further north, on the slopes of Mount Eden, Louise Henderson emphasised the way that lush native ferns and bush surrounding her home filtered the sunlight. This effect can be seen in a series of paintings from the 1960s and 70s that includes the Gallery’s Bush series No.7 where her rendering of the verdant subtropical foliage makes me feel as though I am right there with her, enjoying the soothing dappled light.

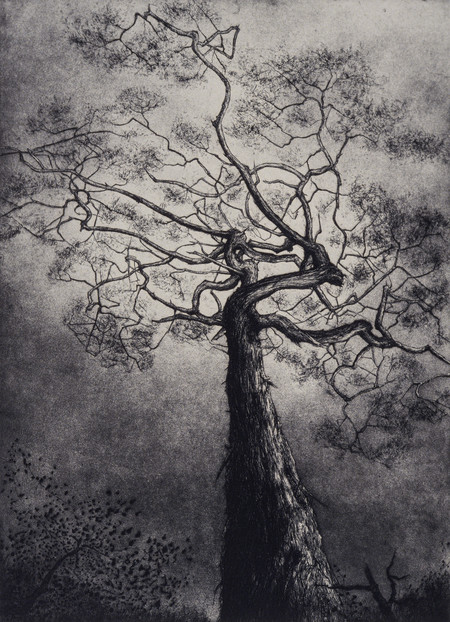

Denise Copland Indigenous V 1991. Etching, aquatint. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1993

The bare branches and trunks of the trees in William James Reed’s Derelicts St Bathans (1947) and E. Mervyn Taylor’s The Hollow Tree (1951) take on a very different feeling. Here the trees seem tortured and twisted, in unsettling, warped and nightmarish views of Aotearoa’s landscape that signal a decaying past through the use of abandoned buildings alongside the dead and barren trees. Similarly, the clearance of New Zealand’s native forests was a central concern for Denise Copland, who used her practice to highlight our destructive impact on the natural environment. In Indigenous V (1991) Copland’s monochrome palette and gloomy tone seemingly highlight the hopeless plight of native trees in the face of capitalist ‘development’. Likewise, Mark Adams’s The ‘Food Basket of Rakaihautu’ from Horomaka, 31 March 1991 (1991) illustrates the loss of traditional food sources for Māori as native habitats are destroyed, with the desolate tree trunk and surrounding stumps offering a stark reminder of the tōtara forests that were burnt and cleared for pasture with the arrival of modern agriculture on Banks Peninsula.

Ana Iti Treasures Left by Our Ancestors 2016. Single-channel digital video, colour, sound, duration 4 mins 40 secs. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2019

As well as representing the damaging effects of capitalist resource extraction, trees also seem to bear witness to scenes where Aotearoa’s colonial history is reassessed from the perspective of contemporary indigenous women. Accordingly, an ecofeminist lens might effectively be used to view the trees featured in Ana Iti’s Treasures Left by Our Ancestors (2016) and Lisa Reihana’s Sex Trade, Gift for Banks, Dancing Lovers, Sexant Lesson (18550) (19205) (2017). In particular, Iti’s video work critiques how Māori history is presented to the public via institutions such as the Canterbury Museum, where her work was filmed. Reihana’s similarly critical view of history was made in response to a scenic wallpaper from the early 1800s titled Les Sauvages de la Mer Pacifique. Reihana filmed her tableau of Captain Cook and his men interacting with Oceanic Peoples in order to highlight how women were fetishised and used as objects for trade like the land and its natural resources, such as the trees and botanical specimens that Cook’s botanist Joseph Banks recorded on the Endeavour voyage. These critical views of our history are crucial in readdressing both the balance of representation in the arts and an understanding of the root causes of environmental destruction. However, another important movement has recently developed, towards forms of critique that inspire hope in the face of environmental crises such as climate change.

Hope is important in the arts today because the capitalist ideology can be described as one of cynicism.1 So while it is important to acknowledge traditional critical emotions such as scepticism, fear and grief as relevant responses to the current environmental crises, artists and critics are also looking for ways to foster hope, through an emphasis on the joy and enchantment inherent to the natural world. Paterson’s The Golden Bearing can be seen as representative of this postcritical movement, because it embodies a view of trees as hopeful and full of wonder.

Enchantment is often deemed uncritical and non-rational,2 and so has been somewhat lost in modern life. Yet if we trace some of the trends in the depiction of trees over time in New Zealand art, The Golden Bearing can be seem to represent a postcritical moment in the development of art that engages with nature themes. It fosters wonder and joy in an era when cynicism and fear regarding environmental crises like climate change abound. The leaves of Paterson’s majestic arboreal vision are designed to flutter gently in the breeze, causing golden light to flicker around them. What better symbol of an enchanted form of nature could we imagine?