In Plain Sight

Margaret Frankel, the overlooked foundation artist of The Group

Margaret Frankel Lyttelton Harbour—Rāpaki (detail) 1939. Oil on paper on board. Collection of Rangi Ruru Girls' School, gift of Margaret Frankel. Photo: Rangi Ruru

Margaret Lady Frankel (née Anderson) (1902–1997) is always listed as a founding member of the Christchurch artistic collective The Group, and is best remembered for her leading role in securing Frances Hodgkins’s Pleasure Garden painting for the Robert McDougall Art Gallery in 1951. However, despite exhibiting more than 100 works, including paintings, drawings, prints and pottery, in the city over a thirty-year period, her art is virtually unknown – hidden in private collections or perhaps lost – and consequently her wider contribution to The Group continues to be overlooked.

Elaine Margaret Anderson was born in Christchurch on 8 October 1902 to engineer Frederick Anderson, owner of Anderson’s Engineering firm in Lyttelton, and his wife Phoebe (née Murphy), known as Mary. She grew up in privileged circumstances with younger sister Geraldine and older brother Terry in a family imbued with a strong commitment to the arts. In 1918 when Margaret was 16 years old the family moved to live at Risingholme, a seven-acre home in Opawa.

From 1913 to 1921 Margaret was taught art by Helen Gibson at Rangi Ruru Girls’ School. She likely enrolled at Canterbury College School of Art after leaving school, since she attended the Arts Ball at the Canterbury Society of Art (CSA) the week before she left to go travelling overseas in April 1923. A year studying painting in Paris was a 21st birthday gift from her parents. There, family friend Cora Wilding probably helped Margaret settle into her studies as she had fellow Christchurch artist, Viola Macmillan Brown earlier in 1923. Cora was relishing life in Paris – living in private hotels, attending painting and life-drawing classes from nude models at popular fauve artist Othon Friesz’s Académie Moderne studio, with visits to the Louvre, contemporary galleries, concerts and theatre in between. Excited by the freedom an artistic life gave single women, Cora wrote to her mother in August 1923: “[O]ne goes on struggling away very happily with one’s work – leading a very selfish but exceedingly interesting life... and being one’s own mistress.”1 Although it's unclear where in Paris Margaret studied, her work did not yet reflect colourful French fauvism. During the summer she was in Brittany studying at Sydney Lough Thompson’s studio overlooking Concarneau harbour, painting plein-air watercolours of houses in the old walled city and hosting Cora for coffee.2

Margaret returned home to her parents and Geraldine at Risingholme in mid-1924. While she was away, her 6-year-old cousin, Kathleen Margaret ‘Peg’ Blunden, had joined the household following the untimely death of her mother, Henrietta. Peg, who is now 104 years old, a weaver and Marlborough’s inaugural Living Cultural Treasure, adored Margaret and well remembers such occasions as sitting at Aunt Mary’s feet in the drawing room as the young Fred Page played the piano, “It was gracious living at Risingholme.”3

![Mothers and daughters undated [1930s]. From left, Olivia Spencer Bower and Rosa Spencer Bower, Margaret Anderson and Mary Anderson. Olivia Spencer Bower archive collection, Robert and Barbara Stewart Library and Archive. Archive 4, Box 3, album 4.](/media/cache/4f/88/4f88611f8566f00f4e1a6d95bbb4dce0.jpg)

Mothers and daughters undated [1930s]. From left, Olivia Spencer Bower and Rosa Spencer Bower, Margaret Anderson and Mary Anderson. Olivia Spencer Bower archive collection, Robert and Barbara Stewart Library and Archive. Archive 4, Box 3, album 4.

Margaret was elected an artist member of the CSA in 1925, with four of her impressionist French watercolours exhibited. In the same year she enrolled for two years at Canterbury College School of Art studying modelling, painting and drawing with friends Edith Wall, James and Alfred Cook, Rhona Haszard, Olivia Spencer Bower and Evelyn Polson (later Page), who was studying part time.4 The students found the academic rigour exasperating, as Margaret told researcher Bruce Harding in 1983, “we all got so sick of having to do these jolly antiques, and draw from the antique for so many hours of the week, then from still life, and so on. And everybody wanted to draw from the model and paint from the model.”5 Margaret and Evelyn found a solution, painting each other posed nude outdoors in the hills near St Martins. Art historian Neil Roberts has attributed the dramatic lightening of Evelyn’s palette to Margaret’s influence.

In 1927, Margaret, Viola and Cora, all single and living at home, founded The Group along with Evelyn, Edith, Ngaio Marsh, William H. Montgomery and William (Billy) S. Baverstock. Together they recreated a bit of Parisian independent studio life in Christchurch. Peg, then 9-years old, remembers tagging along with Margaret when the studio at Cashel Street was found: “I trailed around after them when they were looking for somewhere … to exhibit in Cashel Street. I remember I was only little and I was climbing up these blinky old stairs .... to an awful old room ... on the Whitcombe & Tombs side of street.” Accessed via an alleyway, the disused linotype room on the first floor of the old Weekly Press building was no doubt bleak, but once cleaned up (with assistance from Peg) its brick-lined walls and large windows became a spacious light-filled studio. They opened their first exhibition, Christchurch Group 1927, on 3 August. Photos, now held in the Robert and Barbara Stewart Library and Archive, of Cora’s mainly European entries show her allotted space, establishing the routine for the next fifty years whereby the artists controlled the display of their work. Leo Bensemann noted that Margaret also “firmly controlled” its early finances.

The Group held its exhibitions at the CSA from 1929. Margaret’s fourteen entries that year were of local subjects, among which was a pencil drawing of Peg, a sensitive study observed during the daily ritual of afternoon tea at Risingholme. A small undated oil of Allandale looking across the broad sweep of the tidal flat of the lower Lyttelton Harbour settlement to sunlit hills may be The Curving Bay, another of her 1929 exhibits. It is painted in the high-key complementary greens, reds, yellows and mauves of the fauvists, and like Evelyn Page’s impressionist nude exhibit, Summer Morn, notably lacks a horizon line, which emphasises the painterly patterns. This cropping was a stylistic feature that Christchurch Times reviewer, James Shelley, disapproved of in another of Margaret’s paintings.

![Margaret Frankel The Curving Bay [possibly] 1929. Oil on artist board. Private collection. Photo: Richard Briggs](/media/cache/89/d0/89d0a0c5f3a1466301ffecb9b899df06.jpg)

Margaret Frankel The Curving Bay [possibly] 1929. Oil on artist board. Private collection. Photo: Richard Briggs

Margaret Frankel Old Houses, Lyttelton c. 1946. Oil on canvas. Private collection. Photo: Briar Kinney

Margaret taught art at Rangi Ruru from 1929 and returned to the Canterbury College School of Art to study for a Diploma of Fine Arts, qualifying as a teacher in 1932. She introduced students to oil painting outdoors and lino cutting, catching the modernist enthusiasm for printmaking made popular by Claude Flight of London’s Grosvenor School of Art: in 1933 Margaret exhibited her own linocuts with the New Zealand Society of Artists. For art appreciation, she drove students in her car to the CSA and the recently opened Robert McDougall Art Gallery to view exhibitions, including one of her late colleague Rhona Haszard’s French-influenced work.6

1929 also saw the arrival of the Austrian agricultural scientist, Otto Frankel, and his German wife, Tilli. Margaret, Evelyn, Viola and Fred Page joined Tilli’s monthly salon to improve their German. In 1939, following a long courtship, Margaret and the by-then divorced Otto Frankel married. They commissioned émigré architect and landscape designer couple, Ernst and Anna Plischke, to design their home and garden at 9 Ford Road, Opawa, on a corner of Risingholme gifted by Mary and Fred Anderson. It was the Plischkes’ first private commission in New Zealand.

Margaret painted some striking regionalist landscapes after her marriage. The high viewpoint of Lyttelton Harbour – Rāpaki (1939), with the marae’s small white church and wharenui, Wheke, comfortably nestled in the landscape, has a naïve charm that echoes her interest in children’s art. The painting may have been inspired by Rangi Ruru School’s golden jubilee, as the Ngāi Tahu marae leader, Pāora Taki, had gifted the school its name in 1889. Old Houses, Lyttelton (c. 1946) exhibited at the CSA in 1946 also takes a high viewpoint down the mauve and green St Davids Street over red and pink roofs across the expansive blue harbour to the arc of dry orange and brown McCahonesque hills. It is an exercise in complementary colours sparking off each other, similar to Rhona Haszard’s decorative landscape paintings.

Margaret Frankel Lyttelton Harbour—Rāpaki 1939. Oil on paper on board. Collection of Rangi Ruru Girls' School, gift of Margaret Frankel. Photo: Rangi Ruru

Margaret also taught at Selwyn House and Avonside Girls’ High School, where she introduced pottery classes in 1939. Following her parents’ deaths, she played a lead role with Otto in developing her family home as an art and craft teaching centre. When Risingholme Community Centre opened in 1945, she tutored pottery and invited the young mother Doris Holland (née Lusk) to help.7 In 1947, while a CSA committee member, Margaret began the four-year battle to secure Frances Hodgkins’s Pleasure Garden for Christchurch, rallying support and publicly challenging old friend Billy Baverstock and her former art school teachers in the fight for stylistic freedom and the celebration of individual creativity.

In about 1951 Margaret gave up painting when she and Otto, knighted in 1966, moved to live in Canberra. “I didn’t feel that I was good enough”, she modestly told Bruce Harding.8 She continued with pottery and became a leading force in Canberra Art Club’s push for the establishment of the Australian National Gallery: the couple’s bequest to the gallery continues to secure examples by New Zealand regionalist artists including Colin McCahon, Toss Woollaston and Rita Angus.

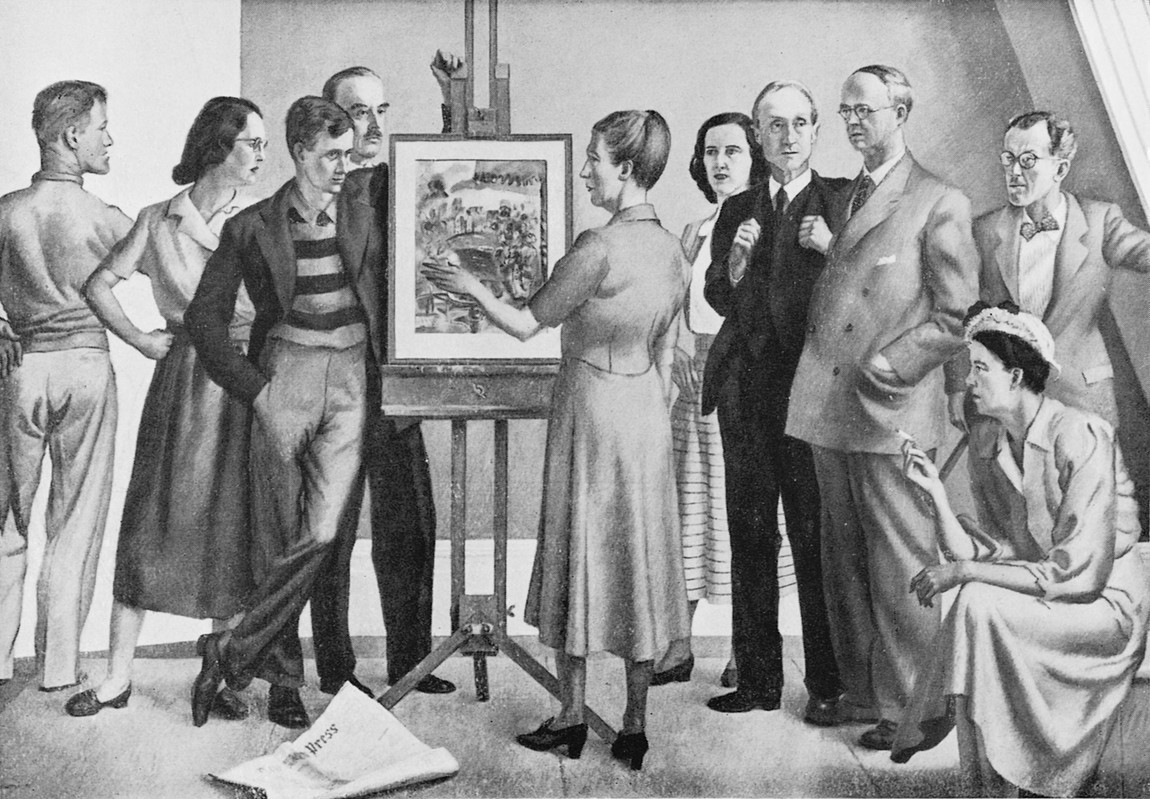

It was no accident Bill Sutton placed Margaret Frankel at the centre of his now-destroyed 1951 painting, Homage to Frances Hodgkins; it acknowledged her status in The Group. Not only was she an influential organiser, patron and teacher, her striking regionalist images highlight the contribution women Group members with training in France made to the stylistic diversity of New Zealand modernist painting.