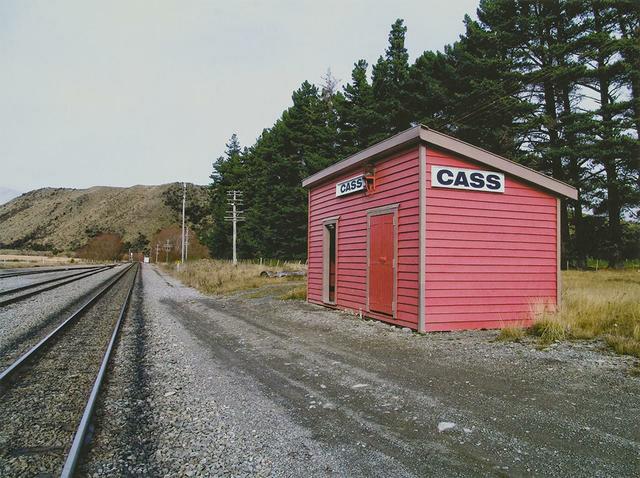

Rita Angus – Cass

Rita Angus Cass 1936. Oil on canvas on board. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1955

A few years ago, I walked the old Ngāi Tahu trails through Kā Tiritiri-o-te-moana The Southern Alps. I was hunting for traces of our pre-European history in the mountains. I encountered a lot of Pākehā mountain history as well. In the upper Waimakariri Basin, on my way to Tarahaka Arthur’s Pass, I wandered into New Zealand’s greatest painting – as seen on TV.

Rita Angus’s Cass depicts the tiny settlement’s red railway station dwarfed by high-country peaks. It’s a hopeful vision of our high country in 1936: piles of sawn lumber, power pylons and train tracks overseen by purple-shadowed mountains and sky. The light is clear, the shadows crisp. An everyman in suit, overcoat and hat dangles his legs from the platform, awaiting his train. I sat where he sat, and ate morning tea in a punishing wind, completing the scene.

John Pascoe photographed shepherds at work beneath the Alps from the 1930s onwards. His radio show brought their camp-fire yarns into city living-rooms. Generations of artists painted dry hills and jagged ranges onto our minds. Here were the hostile Alps humanised through industry, and the more urban our lives, the more alluring the high country became. Today any bookshop will sell you a half-dozen hardcover books full of sheep dogs and acute morning light. There are few close-ups of algal bloom.

I soon gave up on completing the scene. The nor’wester was like a toddler shoving me in the face with each gust, and kept winnowing sunflower seeds from my scroggin before I could jam them into my mouth. In Māori that wind is Te Mauru, ‘te hau kai takata’: the wind that devours people.

At Cass, there were no people. The peak in the background of the painting is Mount Misery, with Mount Horrible immediately to the north. Trains don’t stop at Cass anymore. Pigeons had shat all over the interior of the station, which was strangely womb-like, painted floor-to-ceiling in the same orangey-red as the outside, except for a big, black Bakelite telephone stark on the wall. It’d long since been disconnected from the outside world. I put the receiver to my ear and took a selfie of me talking to myself.

That morning I’d camped at Ōpōreaiti, the mahika kai known in English as Lake Grasmere. In 1880, Arowhenua’s Hoani Kāhu noted that the lake was “he hāpua mahi. Ko te wai kai anō.” I’d spent the last few days trespassing across high country farms in an effort to capture some small sense of our ancestor’s experience of being unwelcome on land you know and love. From first light I’d been climbing barbed wire fences and wading swamps, sneaking across Grasmere Station with curious cows sniffing at my heels. Their owners had spent untold thousands in court trying to gain permission to pivot-irrigate the surrounding land. The judgement spent some time discussing scenic landscape values when refusing their initial consent.

Inside the station, free from the wind, someone had defaced Angus’s painting by scratching onto the wall in crude letters: ‘Kiss the ground you walk on’. I did love the land I was walking across. Though I might come away with a bitter aftertaste, I would still kiss that ground.