Last House Standing

The living legacy of W. A. Sutton

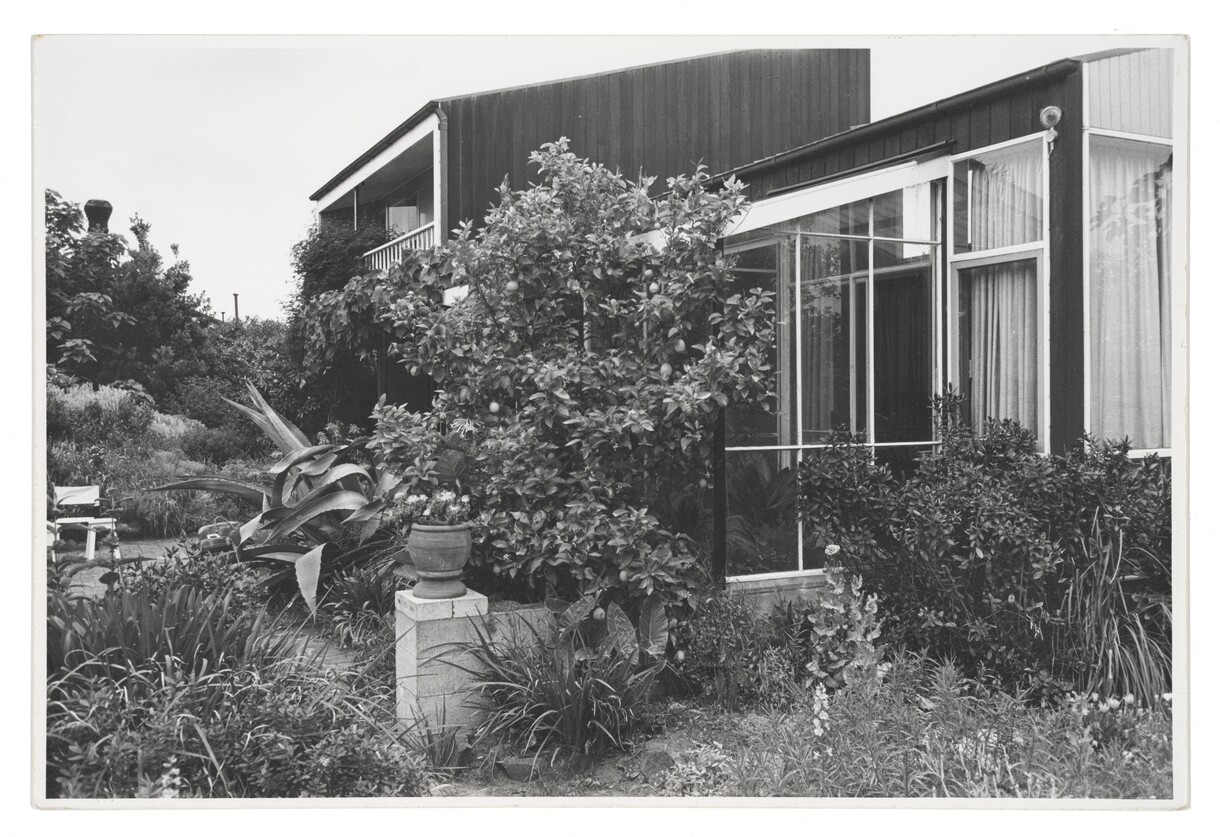

Sutton Heritage House and Garden, 2021. Photo: John Collie

Behind a high-walled garden on the city edge of the red zone, a crooked fig tree peers through the window into what was once the studio-living room of leading Canterbury School artist Bill Sutton.

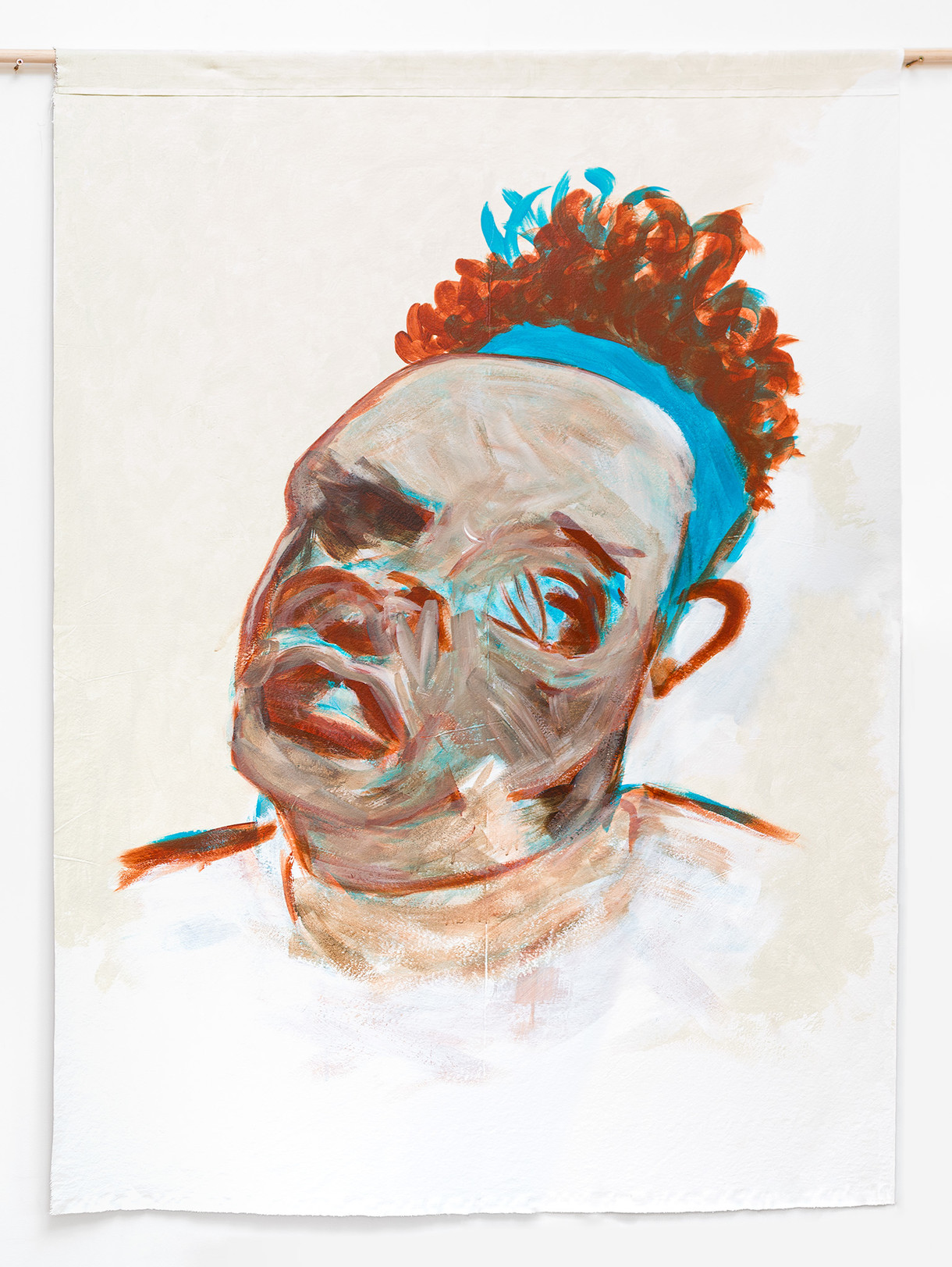

Artist Francis Upritchard working on a sculpted figure in natural rubber, 2021. Photo: John Collie

“I am obsessed with that tree,” says London-based New Zealand artist Francis Upritchard. “I love it—it has such a personality. I’ve done a lot of paintings of that tree.”

Upritchard is the inaugural W. A. Sutton House artist in residence, an initiative set up by Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū and the University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts in conjunction with the Sutton Heritage House and Garden Charitable Trust. Already, two months after moving into the Templar Street property, two sculpted figures – bodies draped in a farrago of refashioned fabrics, shrunken gloves and strange headwear – stand poised on their table plinths in the large, light-filled studio. Outside, below the wheelchair ramp, the figure of Sisyphus, the death-defying trickster of Greek mythology, lies newly formed in a configuration of natural rubber that has been heated, softened, shaped then cooled in large tubs on the driveway under the fig tree.

Upritchard is familiar with her environment. She grew up in Christchurch; she knows many of the Gallery staff now helping her with this exhibition. “It could have been a horrible feeling – parochial and small – but it just feels kind and supportive. The house is cold but it has a warm feeling – it is beautiful, it is quiet, it is of an era I adore, and the light is good, especially the afternoon light. And I love that it was made for art.”

But this house made for art nearly didn’t survive. Following the 2011 earthquake the modernist house, designed for Sutton by his friend and University of Canterbury colleague, sculptor Tom Taylor, and built in 1963, was one of the 5,000 houses slated for demolition as part of the residential red zone along the Ōtākaro Avon River Corridor.

However, the house’s then owner Neil Roberts had other plans. Not only did he want to save the house and garden; he also wanted to give it back to the city as an artist residency and community venue.

This vision dates back to the late 1970s when Roberts, then senior curator at the Robert McDougall Art Gallery, began to promote the idea of a permanent artist in residence programme linked to the gallery. When Olivia Spencer Bower died in 1984, he suggested using her Merivale house and studio as a residency, but the Olivia Spencer Bower Foundation didn’t want to own property and the artist hadn’t gifted the house in her will. Following Sutton’s death in 2000, Roberts suggested the W. A. Sutton Trust give that house to the art gallery. It seemed ideal. The house was one of the few buildings designed by Taylor; it was designed specifically for an artist; and it said much about Sutton himself – his art, his aesthetic and his famous sociability (Taylor’s daughter, Bridget Cassels, recalls helping her parents clean up the aftermath of Sutton’s 50th birthday toga party). As former Christchurch Art Gallery curator Lara Strongman wrote, the small two-storey house reveals the tension “between modernism and the colonial, which was such a pivotal dynamic in the development of New Zealand twentieth-century culture, and which was a major aspect of Bill’s own work.”1

But again, there was nothing in Sutton’s will to support such a venture and the Trust needed the money from the sale of the property. In 2006, Roberts decided to buy the newly covenanted property himself with a long-term goal to leave it to the city.

Interior of the Sutton Heritage House, showing Sutton’s easel. Photo: John Collie

Sutton Heritage House and Garden, 2021. Photo: John Collie

The 2011 earthquake fast-tracked that goal. By 2014 the house stood alone in a ‘ghost street’ of empty red-zoned land – uninsured, almost valueless and vulnerable to burglaries. Eventually he sold the house to the Government but, with the backing of Dame Ann Hercus, efforts to retain the house and garden continued to grow. They finally won through in 2018, when Land Information New Zealand (LINZ) spent $650,000 from its red zone maintenance budget to restore and upgrade the house before transferring ownership to the Council. The newly formed Sutton Heritage House and Garden Charitable Trust would be responsible for the day-to-day operations and maintenance of the house and property while the artist residency would be managed jointly by Christchurch Art Gallery and the Ilam School of Fine Arts at the University of Canterbury.

The timing was fortuitous. Christchurch Art Gallery director Blair Jackson had lined up an exhibition with Francis Upritchard for late 2021. The artist needed a place to live and work. The Sutton house stood newly restored and empty on the park-like fringe of the red zone. “If ever there was a time to launch the planned artist in residency programme,” he reasoned, “it was now.”

Jackson had long supported the idea of using the Sutton house as an artist residency. In managing the Dunedin Public Art Gallery residency programme during his time there, he had seen at first hand the benefits such residencies bring to cities.

“It is an opportunity for an artist to have time and space but you also see the effect of that injection of new people, energy and ideas. And you end up with a team of international ambassadors talking about your gallery and making recommendations for other artists they think they would be great in this situation. So it is international marketing, a way of spreading the word.” In this instance, it is also about activating “a really great house.”

“I love the light, the space, the garden, the environment of the Sutton house.”

While Upritchard is using her residency to make work for her forthcoming exhibition at the Gallery, this is not a prerequisite for future residencies. “From our point of view there may be exhibition outcomes but it is more about working with the artist to see what opportunities they would like and what opportunities the house gives the Gallery and the art school.”

Aaron Kreisler, head of the Ilam School of Fine Arts, knows all too well the value of such residencies. His father, Tom Kreisler, helped set up the Govett Brewster artist in residency programme after being the inaugural recipient of the Trust Bank Canterbury artist in residence at the Christchurch Arts Centre in 1989. “He thought it was a great way for artists to spend time in the community.”

The benefits of the Sutton house residency, he says, are myriad. The visiting artist is able to make new work and access studio facilities at the school; the university is celebrating the work of two alumni; and students will be able to engage with resident artists through presentations and in assisting them realise new projects, “so there is some real-world knowledge being passed on, which you can’t put a price on.”

Artist Francis Upritchard working on a sculpted figure with a student from the Ilam School of Fine Arts, 2021. Photo: John Collie

Interior of the Sutton Heritage House. Photo: John Collie

The residency will also put Sutton’s legacy within a more contemporary context, outside the Canterbury School category that has defined his career to date.

“When artists are dealing with history it doesn’t have to operate within the same boundaries as other forms of academia – it can be more tangential, more speculative. On another level, it still keeps a level of mystique in terms of the history of the house.”

As trustees of the Sutton Heritage House and Garden Trust, Jackson and Kreisler are both keen to avoid the pitfalls that can beset artist residences. While three to six months to spend a sustained period on your practice sounds a dream gig, says Kreisler, the success of a residency can hang or fall on the level of pastoral care given to the visiting artist.

“If we invite an artist we would ensure they were warm and welcome and looked after,” says Jackson. “It is that whole manaakitanga of hosting and looking after somebody.”

They are also determined that the house itself is seen not as a staged memorial to its original owner – a common pitfall for heritage house museums – but rather as a space that is lived in and activated. The most successful house museums, writes public policy professional Sebastian Clarke, are those that maintain a changing programme of exhibitions and events involving artists, audiences and new curatorial approaches to interpretation. To be frozen in time, he writes, “is a curious fate for any place.”2

“In my mind, the house and the garden are such a statement about who Bill was,” agrees Jackson. “The house doesn’t need to be filled with paintings and the history of Bill Sutton as such. It can at times tell that story but it does not need to be permanent. The last thing an artist wants to come into is a place where another artist exists.”

The ghost of Sutton does not crowd these rooms. There’s an easel and a chair which belonged to the artist; the garden he planted still fruits and blooms, a portrait photograph hangs in the kitchen. But for now, the rooms give space to Upritchard’s own art and aesthetic – her painting of the fig tree hangs above the sofa, ceramics bought from the op shop around the corner line the shelves, the work and found objects of fellow artists and collaborators line the studio.

By the end of April, these had gone. Upritchard and her husband, Italian furniture designer Martino Gamper, had left for their home in East London.

Roberts is still hoping his original plan for a new building to be built on the adjoining site will transpire. As with the McCahon House artist residency in Titirangi, this would allow for residencies throughout the year, leaving the original house open for other community events or temporary exhibitions.

In the meantime, on the other side of winter, a new artist in residence, Melbourne-based performance and installation artist Alicia Frankovich, will be carving out a temporary home and working space within the large light-filled living spaces and the small bedrooms upstairs looking out over the curiously crooked fig tree.