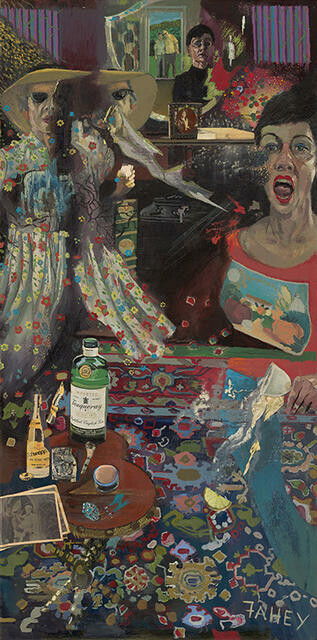

Jacqueline Fahey Mother and daughter quarrelling 1977. Oil and collage on board. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1983

Jacqueline Fahey's Mother and daughter quarrelling

I first encountered Jacqueline Fahey’s Mother and daughter quarrelling (1977)—in reproduced form—in Art History class during my final year at Shirley Boys’ High. We’d just entered the new millennium and at some point amid that final year our entire form group lost access to our senior common room for a week because a couple of boys had sellotaped a selection of pages from some off-brand Penthouse onto the roll-up projector screen that hung from the ceiling. That’s just to give you an idea of the prevalent gender politics of the time and place.

Fahey’s painting was my introduction to feminism in art, in art history, in any kind of representational form actually. It was a striking example of what feminism could look like and why it was important. In class, the work was presented alongside Judy Chicago, Allie Eagle and Georgia O’Keefe. I can still see their works printed on the glossy, stapled A4 handout during the final bursary exam. I loved, and still love, the energy of Fahey’s painting; it feels like a puzzle to solve—complete with unreliable narrators and hidden clues. In many ways it’s a perfect ‘Art History’ painting, there’s a lot to read and my teenage brain was eager to apply some of the textual analysis framework I’d picked up. The action moving from the foreground into the background. Overlapping spillages, breakages, cracked and split personas. Memory and time bleeding into one. The use of collage. The domestic scene as a site of significance and resistance. And the patterns! The way the Persian rug segues into the mother’s dress…

Great art reframes your memories and provides new perspectives through which to view your life. Growing up, weekly on Sunday mornings my family would visit my maternal grandparents’ flat inside Rawhiti retirement village to have a G&T and a catch-up, usually bang-on the yardarm. My pop, who made the drinks and did the weekly shop and the cooking, would always have a stock of the small glass bottles of Schweppes tonic like the one you see in the foreground of Fahey’s painting. Mum and Nan would go outside and smoke together. It was drama-less.