Artists Should Be Giving Business Advice

(and other unlikely pandemic response policies)

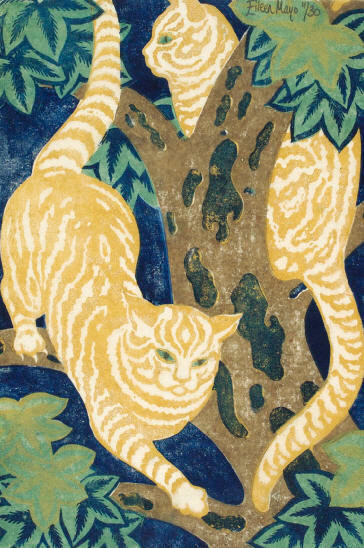

Free Theatre Kafka's Amerika 2014. Photo: ©cmgstudios

There has been a healthy debate going in relation to Germany’s Covid-19 emergency fund, which allocated the equivalent of NZ$900 million to artists and freelancers, with extra support from the Berlin municipality, leading some to call it an ‘arts-led’ (as opposed to ‘business-led’) approach to recovery. Some in Germany are claiming this will have better long-term economic outcomes, whilst addressing social and wellbeing recoveries at the same time. Others – without necessarily denying the first claim – fear gentrification and the instrumentalisation of arts, when it’s overtly being used as a tool for the economy.

We are at the beginning of a comparable debate here in Aotearoa, as the government announced a NZ$175 million recovery fund across Arts, Culture and Heritage (per capita, even higher than Germany’s). Most of the details of this collection of funds are still being developed, with the funding structures and eligibility criteria due to be announced as this magazine goes to print. According to the Ministry for Culture and Heritage website,1 around $45M will go explicitly to a Covid emergency response to retain cultural infrastructure, assist creative jobseekers and address other sector capability needs. Another $70M is to support new creative projects with the number one aim being job creation. $60M is tagged to encourage investment and cross-sector innovation. I’m hopeful that this package might achieve not only a recovery for the arts sector, but will also put the arts at the forefront of the whole country’s recovery and response – economically, socially, environmentally, and in less classifiable ways.

In post-quake Christchurch, we certainly didn’t have an arts-led recovery in terms of government policy or funding. But the arts were prominent among the early responders in the recovery, giving people reasons to come back into the city, imagining the possible futures, providing outlets for expression and generating social life whilst businesses and city planners were undertaking much slower aspects of the recovery. The impact was huge. It was precisely this creative response that got Christchurch plaudits on the BBC, and in Lonely Planet, the Guardian and the New York Times – which boosted tourism and also changed locals’ perceptions and the sense of community pride, identity and potential here. I sometimes wonder what we might have achieved if this approach had actually been resoundingly backed by those in power.

As one of the founders of Gap Filler, I’ve been asked numerous times in recent months to reflect upon the earthquakes in Christchurch and what lessons, if any, might be applicable during the current pandemic or in the immediate post-pandemic period. There’s a lot of interest in the ability of art to be a first responder: to be more nimble; to critique, and express optimism and more complicated emotions in constructive ways; to give voice and shape to the place and push forward an authentically local recovery. This is all true, and borne out by case studies all around the world.

But there’s an even deeper role that the arts should be playing in our country right now.

At a time of so much local, national and global uncertainty, nearly every business, sector and agency needs to develop an ability to operate strategically and purposefully whilst balancing many, many things outside of their control.

How do you steer a company or organisation through so many layers of uncertainty: What will the virus do? Will the government move us back to Level 1? What will the new restrictions be when they come into place? What’s happening with this contract and that contract, and with the local economy as a whole? Will we still have customers? And further afield: how bad will the global recession be, and how might it affect us?

Making a new five-year plan, or even an annual plan, at such a moment feels absurd. Anything approximating traditional planning seems daft. Develop objectives; outline the tasks required to meet those objectives; determine what resources will be needed to implement the tasks; create a timeline; determine a method of tracking and assessing progress… Very little of such a process is within our control when there’s a high likelihood we could be back at Alert Level 3 in the next six months; or when – 100% outside of our control – Melbourne has a fresh outbreak and the trans-Tasman bubble is off. But there’s a certain strand of arts practice and creative process that is entirely comfortable in – or even prefers – this space of responding to external constraints and variables rather than having total control.

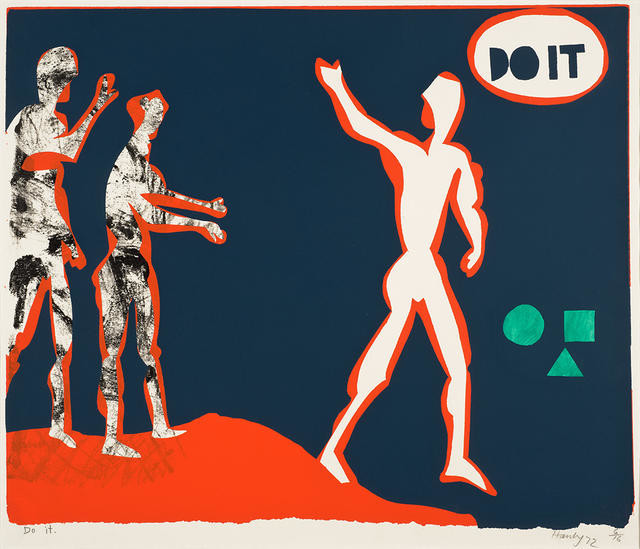

Prior to and in the early days of Gap Filler, most of my experience of creative practice (from 2000–13) was with Christchurch’s Free Theatre, New Zealand’s longest running producer of avant-garde theatre. Most of the works I was involved in were ‘devised’ theatre. That’s a broad and varied term, perhaps easiest to understand via a comparison. A mainstream theatre typically occupies a particular theatre building and has a small troupe of actors on the payroll. It programmes its season well in advance, which involves choosing which plays it will put on at what times over the next year or two. The texts having been chosen, the main roles are cast, the promotional poster photos are taken, tickets go on sale – and some time perhaps eight weeks out from opening night, sets and costumes will be designed and made, actors will learn their lines, and it will all come together via an intense rehearsal process. It’s unquestionably creative work, and yet perhaps 80% of the possible creative decisions have been made before rehearsals begin – many via the selection of a pre-written playtext.

A new Free Theatre production would typically start with an idea, issue or topic of concern – for instance ‘state surveillance’ at a time when Edward Snowden, the GCSB and the Five Eyes Network were all prominent in the news. Ensemble rehearsals would begin with nothing decided other than that theme, and everyone would begin to make relevant contributions and explorations: characters and text from real life (e.g. a Julian Assange manifesto); text or bits of narrative from literature (e.g. Kafka); relevant theoretical concepts (e.g. Bentham’s panopticon); songs or styles of music; forms of dance, martial arts or movement and more. Even the venue for the production would be decided partway through the rehearsal process based upon the needs of the theme: would it be a ticketed show in a theatre, or in a church? Would it be a guerrilla street performance? Slowly, over time, the artistic director would assemble all these raw materials into a score: something like an outline of the main sequence or ‘movements’ of the production. Up until opening night (and often beyond) it would remain fluid, able to adapt and incorporate the latest news headline, or another topical discovery by one of the ensemble members. This creative process is far less linear than the former, operating with more variables and uncertainty, more creative cul-de-sacs that were explored and dropped, radical changes of direction, late returns to earlier abandoned concepts, and so on.

This mode of creative practice seems more salient (and ignored) than ever in this pandemic era. Artists and arts organisations are often encouraged – or, as at the moment, directed towards new support funds – to get a business mentor and/or financial advisor to help them make a living out of their practice. Post-lockdown, all businesses are being encouraged to access such support: ChristchurchNZ and the Regional Business Partner Network have been offering small grants for almost anyone to access professional business advisory services in areas such as HR, business continuity, cashflow and finance management.2

I’d like to suggest that programmes like this should be extended to help businesses and agencies access creative advisory services from those in the arts – to help the businesses navigate uncertainty and treat external constraints as the terrain to which they creatively respond.

The Dance-O-Mat. Photo: Gap Filler

Free Theatre Kafka's Amerika 2014. Photo: ©cmgstudios

Just a couple of weeks ago, as I write, Steven Moe and Anne Rodda put out a paper, Tomorrow’s Board Diversity: The Role of Creatives, calling for more artists in governance positions of both arts and non-arts companies and organisations – especially given the new paradigms of thinking necessitated by Covid-19.

They write about the skills creatives bring:

If we associate ‘hard skills’ with technical knowledge, then it is understandable why we have been accustomed to appointing accountants, lawyers and similar technicians to boards in the past. ‘Soft skills’ has become a buzz word more recently embodying characteristics such as resilience, collaboration, work ethic, empathy, adaptability, persistence, self-discipline, targeted and flexible communication tactics and problem-solving prowess and are perhaps better termed as ‘humanistic skills’. These personal competencies really do contribute and make a difference, yet we have previously and passively hoped that these attributes would simply reside in our assembled directors and trustees rather than specifically recruiting for them or making them a part of our skills matrixes.3

This distinction between hard (technical, tangible, infrastructural) and soft (humanistic, complex, operational) skills and systems is also used in the field of urban design. The sub-field of placemaking, which is Gap Filler’s primary focus, emerged from the premise that the hard, technical disciplines such as building design and traffic engineering have been given preeminence in our cities’ designs for far too long. Placemaking sets out to redress this imbalance by advocating for social interactions, civic life and all things soft. A general principle might be that the built things of the city are just vessels for the soft transactions and interactions that happen amongst them, and we should construct (hard) the minimum thing required to achieve the soft, humanistic outcomes.

Our Dance-O-Mat project is a simple example: the built thing is just an empty space with some speakers and lights, and a system to play music. It’s the minimum expression of a dance space, but more than enough to have facilitated thousands of memorable experiences and social interactions. Markets are similar: a good bit of land, some easy-up tents, a musician and some advertising are all that’s needed to create a vibrant social space and bring about lots of economic transactions as well.

My friend and colleague David Sim, of Gehl Architects in Denmark, recently published a book called Soft City: Building Density for Everyday Life that sums up this approach. He thinks about cities primarily as a series of relationships: between people and place, people and planet, and people and other people. “The starting point is not a big, architectural urban idea – it’s about being a little human being, and how you can connect that human being to as many experiences as possible,” he says.4 Good cities, from this perspective, are ones that maximise the opportunities for such connections to be made.

The overvaluing of the hard has pervaded many disciplines and sectors (and arguably caused the overuse of words like ‘disciplines’ and ‘sectors’).

Rather than (tending towards the hard) planning, the Gap Filler team has been talking about (much softer) preparedness. What can we do right now so that we have multiple potential paths that we’re happy and ready to follow? Who should we be talking to now so that we have a direction to turn towards if a whole segment of our work is indefinitely on hold? How can we treat the ever-changing restrictions and context as the constraints to which we’re creatively responding?

We have developed a sort of system over the years for cultivating purposeful opportunism. We keep, in a manner of speaking, three separate lists that we constantly update. The first list comes from our observations about a place, conversations with people on the street, historical research, embeddedness in a neighbourhood. We develop a strong sense of the context in which we’re operating: what’s on people’s minds, what issues are in the air, what’s lacking, what boundaries can be pushed. From this we develop some high-level objectives: based upon the place and its people, what should we be trying to achieve here?

The second list features the resources that are – or could be – available. A resource could be money, or materials, or very often it’s a person or group and their skills or passion. Many potential resources can only be ‘unlocked’ by the right enticement. Lisa and her gardening knowledge are a valuable resource, but she’ll only work with us if we’re doing a project that’s promoting her passion of biodiversity.

The third list, then, is champions with ideas for what they’d like to do. Very few creative ideas, no matter how sound and appropriate, will fly if there’s not an energetic person to keep them going. All three lists are constantly being refreshed. Some of the objectives might remain relevant for years; others might have only a short window of relevance.

The purposeful opportunism comes from constantly trying to draw connections between the three lists until we find a match. Some potential projects or pathways never come to fruition, or sit there for ages with a clear objective and resources waiting for the right champion to come along. Often there’s a fun idea, champion and some resource but no clear social objective or purpose. So we wait until the idea finds a reason to be.

There are many such systems for opportunism, which is an alternative (or at least complement) to traditional planning. Any such system is based in humanistic skills: sensitivity to the context one is living in, an ability to read the patterns and trends, human interactions and the valuing of lived experiences over detached analysis. Such skills and systems have been undervalued for generations. My hope is that the unpredictability wrought by Covid-19 might necessitate their resurgence across all facets of society, not – or not only – out of desperation, but with the conscious support of things like the government’s cultural response fund.