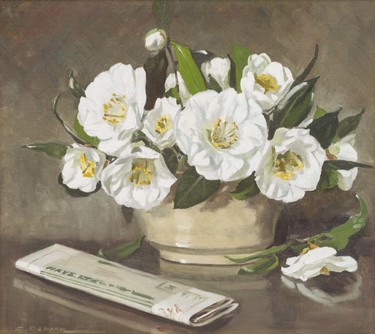

Daisy Osborn From My Garden – White Camellias c.1951. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, presented by the artist, 1953

White Camellias Revisited

Just over a quarter of a century ago the Robert McDougall Art Gallery hosted an exhibition to celebrate a century of women’s art making in Canterbury. It was the Gallery’s contribution to the country-wide centenary celebrations of women’s suffrage. Co-curated by Lara Strongman and myself, White Camellias: A Century of Artmaking by Women in Canterbury, as its title suggests, was a springboard for both korero and further study of women’s art history.1

The task was slightly daunting, not only for the need to select a cross-section of work made over a century, but also because of the realisation and acknowledgement of the gaps in collecting and scholarship. While Canterbury women were well represented in terms of art school attendance and exhibiting at the Canterbury Society of Arts (CSA), they fell short in both the Gallery’s collection and in the iconic texts about New Zealand, and more specifically for our purposes, Canterbury art.

The title for the exhibition came from the painting From My Garden – White Camellias (c. 1951) by Daisy Christina Frances Osborn (1888–1957). 2 Two years earlier, in my fortnightly column for the Press, I had profiled Osborn’s still- life painting of a vase of white camellias and a copy of the Hay’s department store newsletter. Selected on the grounds that there was very little known about Osborn, she was a good subject to explore. The work had been gifted by the artist in 1953, and yet had never been exhibited at the Gallery. 3 Was this because it was yet another flower study by a woman, or was it because Osborn wasn’t a significant name in the bigger picture of Canterbury art? I felt Osborn and her painting were deserving of attention, and I made a request for readers to come forward with any information about the artist. Seventy-five people responded, setting me on a journey to find more; I discovered a responsibility to contextualise Osborn’s oeuvre, and to make sure she wasn’t lost again in our country’s art history. 4

An only child, Osborn grew up in the Christchurch suburb of Linwood. She enrolled at the Canterbury College School of Art in 1906, and for the next two decades she enjoyed an association with the College, either as a student or a part-time teacher. Like many of her female contemporaries, her career aspirations were framed by her domestic circumstances, which in Osborn’s case included caring for her elderly parents. Osborn blossomed at the College and picked up many student awards; her repertoire was wide and representative of the teaching and the time. She made exquisite jewellery, designed the cover for the School of Art syllabus for 1914, illustrated children’s chapter books and painted a variety of subjects. But it is for her still-life works that she is best remembered, given both her prolificacy in this subject area and the fact that she gave them away as gifts to her many friends and relatives. Like those who went before her, as well as many of her peers, flowers from her garden were a go-to subject. But Osborn’s repertoire was far wider; in particular the interwar years saw her explore religious subjects that give greater insight into this much-overlooked artist.

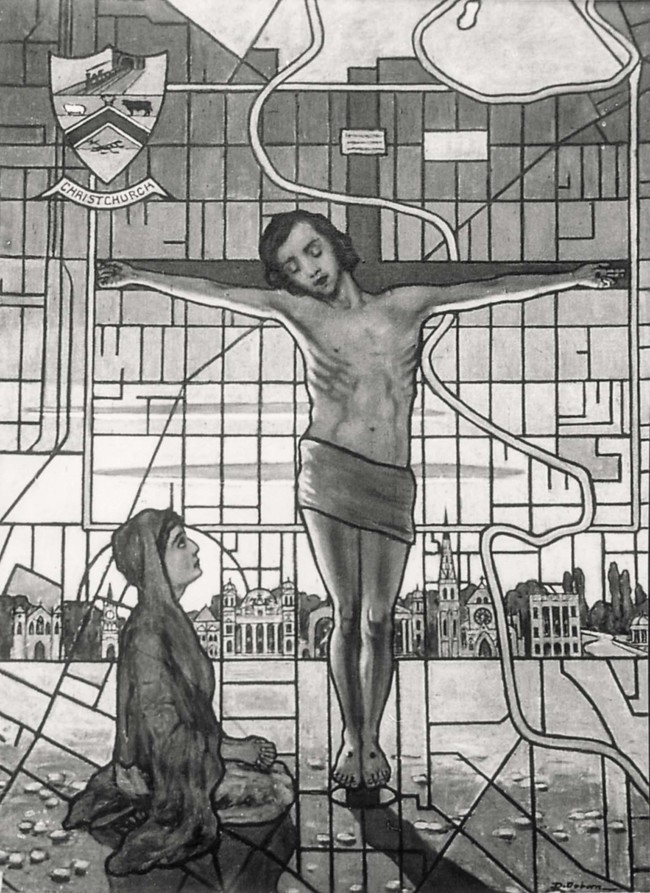

Daisy Osborn Lo, These are parts of His Ways c. 1930. Oil. Location unknown

In 1930, Osborn exhibited Lo, These are parts of His Ways at the CSA’s annual exhibition.5 In it a youthful Christ figure on the cross and a kneeling Virgin Mary are set in Osborn’s Christchurch. Osborn gave the work a biblical title from Job 26:14 – a text which also appears above the main entrance to the Canterbury Museum, carved in 1896 by Claudius Brassington (1873–1945) and located just across the road from the College. The overall effect is that of a stained-glass window, very much in keeping with the subject matter. The grid-like pattern is a simplified map of the city; the only concession to the myriad of straight lines is the meandering Avon River. From left to right, a line-up of significant buildings and landmarks posit it very much in Christchurch: the Durham Street Methodist Church, Victoria Street Clock Tower, Canterbury College School of Art, the Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament, the Bridge of Remembrance, St Paul’s Presbyterian Church, Christchurch Anglican Cathedral, the Government Building in Cathedral Square, and the Band Rotunda. The row of secular and religious buildings creates a strong line across the composition. This is even more poignant now for many of these buildings were damaged or destroyed in the 2010 and 2011 earthquakes.

As a child Osborn attended the family’s local Anglican church but as an adult she visited churches of all denominations. The many churches that feature in Lo, These are parts of His Ways are perhaps a reflection of this. The work was exhibited in the Society’s Jubilee Year. As it was a celebratory year, the exhibition was larger than usual, hosting a staggering 552 pieces of art. Fifty years of the CSA was celebrated with the acquisition of two works for the gallery’s permanent collection. 6 At the exhibition’s opening Osborn’s painting was awarded the Billens Medal, presented for the best original work. 7 The following morning, the Press described the opening as one of the most important social events of the year and detailed the dress of every woman who attended. Sadly, there was one notable omission – Osborn. Family later suggested to me that Osborn, who at the time was aged 42, didn’t attend for she lacked both a suitable dress and a chaperone. A review published the following week, described Osborn’s winning piece as the fi purely symbolic picture to have graced the walls of the CSA. 8 The work’s whereabouts are today unknown and it is known only from a black and white photograph.

Throughout the 1930s Osborn continued to make and exhibit works of a religious nature. She was not alone in her pursuit; friend and fellow artist Rose Margaret Zeller (1891–1975) also explored religious and spiritual subjects. 9 Zeller’s works, like Osborn’s, were either of churches or aspects of spiritual interest or devotion. Both artists explored other religions outside of Christianity; Osborn was a theosophist and with Zeller, practiced mysticism. Osborn challenged the role of women and the Holy Trinity, arguing that the Trinity contained only males and therefore was incomplete. Her foray into questioning religious beliefs also extended to her writing; in her book The Good of Eve-el, published around 1940, much attention is given over to the gods and the linguistics used in conjunction with them, for example, “Run some of the letters backwards; EVIL becomes simply LIVE, and DEVIL only LIVED!!” The book’s finale reads “GOD LOVES THE DEVIL”. 10 In hindsight, Lo, These are parts of His Ways, was the most orthodox of Osborn’s religious works.

Daisy Osborn Gods 1938. Oil. Private collection

In Gods (1938) Osborn presented a still life full of objects of worship, though admittedly rather masculine ones given the time: drink (grapes, wine bottle and glass), gambling (cards and coins), sport (the silver trophy, tennis racquet, golf clubs) and smoking (the pipe) are all vices of the material world that humankind can succumb to and worship, like a god. A Buddha and the Virgin Mary with Child represent the spiritual world. Distinctively New Zealand, the work also contains taonga Māori including a korowai. Gods was purchased by the CSA from their annual exhibition in 1938 and in 1940 it was exhibited in the National Centennial exhibition of New Zealand Art in Wellington. 11

From 1931 to 1945 Zeller also produced works of a religious and spiritual nature. Her choices for the CSA’s annual exhibitions support this and included representational depictions of churches including Bishop Selwyn’s Church, Auckland (exhibited 1931), Symbols (exhibited 1936), Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament (exhibited 1941) and Little Church (exhibited 1945). Others with titles such as Prayer, Faith, and Peace alluded to more spiritual content. Zeller also explored the crucifixion though her Untitled (Crucifixion). Although her painting is a far busier and more energised scene than Osborn’s Lo, These are parts of His Ways, she also chose to set it in Christchurch – the two cathedrals can be made out, and on the cross the abbreviation “CH CH” confirms the location.

Photograph of Rose Zeller and Daisy Osborn, Christchurch, c. 1940s. Hand-coloured by Daisy Osborn

Somewhat of an enigma, neither Osborn’s or Zeller’s objectives are fully known to us, but it is empowering to think of these two artists challenging traditions. As Julie King has noted, given the historical context their paintings could be considered as expressions of faith and despair. 12 But their oeuvres are gutsier. They were far more adventurous with differing results and reception. As an example, in 1982 fellow artist and friend of Zeller’s, Henry Maitland Tomlinson (1904–1986) offered a selection of her work to Dunedin Public Art Gallery – Zeller had taught at Dunedin’s King Edward Technical College from 1915 to 1924 and Tomlinson thought it a suitable gesture. Two works were chosen and on the copy of the thank you letter, from director Frank Dickinson, a handwritten note supposedly by a staff or board member with the initials T.G. reads, “must we accept this awful stuff ”. 13 In short, Osborn and Zeller proved that they were not just the painters of flowers; though they both also painted traditional subjects they acquired an alternative repertoire that reflected their philosophies and beliefs and challenged them (and their audiences) artistically.

From My Garden – White Camellias gained a new lease of life in 2018 when it was exhibited next to a 1966 still-life painting by Ida Harriet Carey (1891–1982), 14 Untitled (Camellias in the Afternoon). 15 Carey’s camellias were picked fresh from the artist’s garden, and painted in a representational manner. Although it is more than likely that both artists chose camellias to paint for their availability (the climatic conditions in both Hamilton and Christchurch are well-suited to camellias), the fact that both Osborn and Carey painted the flower Kate Sheppard gave to the supporters of the women’s suffrage bill is significant. White camellias have become a national symbol and both paintings have been useful in showcasing stories about art, women and politics. The Suffrage125 celebrations are now behind us, however they shouldn’t be forgotten. Significantly, they were an opportunity to revisit our female artists as we did 25 years previously; going forward they should also be about strategising. What must we collect and exhibit in order to make our art history more inclusive of women artists, both past and present, so that in another twenty-five years we’re not having the same conversations?