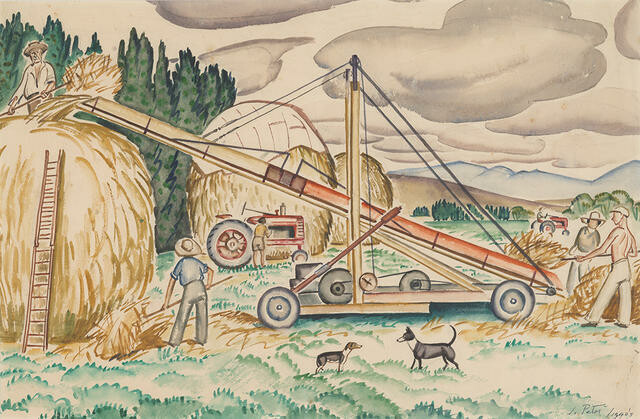

Juliet Peter's Harvesting, Rydal Downs

Juliet Peter Harvesting, Rydal Downs c. 1943. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of Alastair and Gaelyn (Ensor) Elliott, 2018

I grew up in a house in Glandovey Road, Fendalton—twenty-two bedrooms! Back then, my options were to be a nurse or a school teacher, but all my life, I’d wanted to be a farmer. My father encouraged that practical side of me. He was a keen fly fisherman and called me “sonny”. I had my hair cut at the barbers; I wore long pants in winter—I thought I was a boy.

[When compulsory conscription was announced in 1942] I was studying commerce at university and working part-time in an office. When I got my conscription letter I went straight down to the War Office, walked in and said “I want to work on a farm, to be a land girl.” I had no experience, and they didn’t want me, but I didn’t give up. Finally, they gave me a trial on a property at Windwhistle farmed by an excellent, tough woman, Mrs Richards. She asked me, have you ever milked a cow? I hadn’t. She showed me the cow and the stool and said “there you are”. I set to work—that poor cow—and discovered I could do it. When she came back to find a pail full of milk she said “You’re a natural.”

In 1943, I was at the dentist getting all my wisdom teeth out when I got a call from the Land Service to say that a Mr Ensor needed to get hold of me. His number one tractor driver [artist Sylvia Ragg] had broken her leg and was in hospital. “He needs someone cheerful who can drive a tractor. He only farms with girls, you’ll have three housemates and he wants you in the morning.” I got the twelve o’clock train from Papanui to Rangiora and was ready for work the next day. I was at Rydal for three years in the end, and they were the best years of my life.

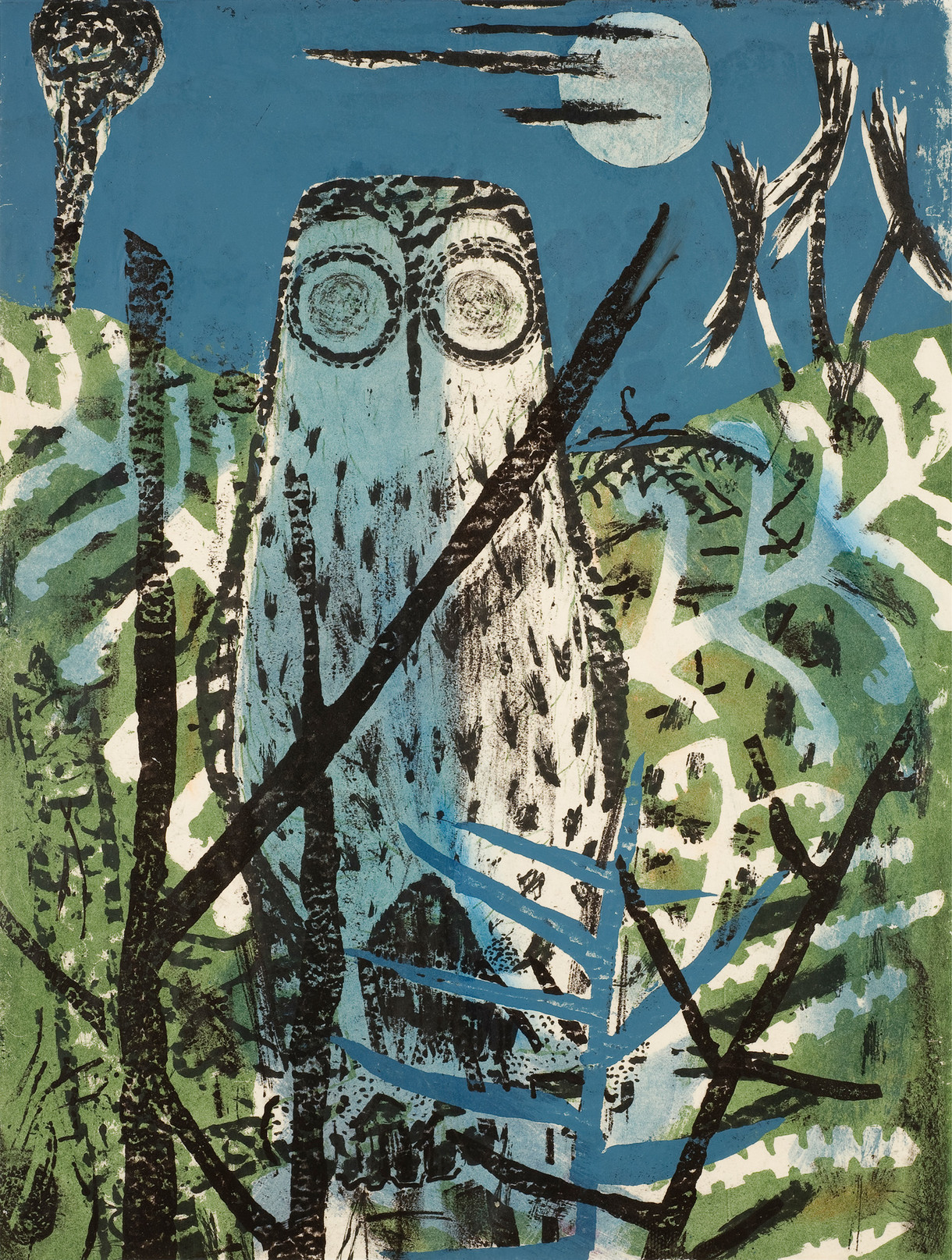

Juliet made this painting early in my first summer there. That’s me with the Farmall M tractor and the others are stacking the oats. I would have driven the tractor there with the sheaves on it. It took a lot of precision to build a stack properly—it could stay up for five years if it was done right.

Fixing the tractor was quite typical for me—it often needed looking at if you turned it off. I was probably cleaning the spark plugs. I remember watching Juliet when she would sketch at the end of the day. She held the flat pad in her hand, sketching without looking—Mr Ensor was very proud of her ability to do that. He would take her to the sales and once she was home she would drop her sketches of the day on the kitchen table for us to see.

By the time VJ day came, Juliet had already left for Wellington. We thought we’d be invited to have a part in the celebrations, but we weren’t even mentioned. We weren’t recognised, we weren’t official. We naturally thought if every other Tom, Dick and Harry, girl guide, boy scout, Red Cross—you name it, they were all there—was we would be too, but no. So we took it upon ourselves to run our own show, which we did, very satisfactorily. We turned up at the beginning of the parade, to be told, “no, you’re not here officially, go away.” We said “fine” and we went to the other end where the parade was meant to finish, and set off from there. Three girls, seven dogs, in full regalia—jodhpurs, stock whips and all sorts. Judy and Ann had the dogs speaking up more often than they were quiet. We got cheered, we got things thrown at us, people rushed out and hugged us and we were the stars of the item. We met the parade coming back the other way, but everybody flocked to our side of the road. It was really very funny. And we didn’t behave any better later in the day. I climbed up on the veranda of the United Services Hotel in the middle of the Square and made a speech. God knows what it was about, I don’t think anybody listened, but they all thought it was hilarious and they clapped and screamed. And then we went back to the farm and carried on, but the end was nigh.

Extract from an interview with Felicity Milburn, 28 September 2018.