Tony de Lautour's Underworld 2

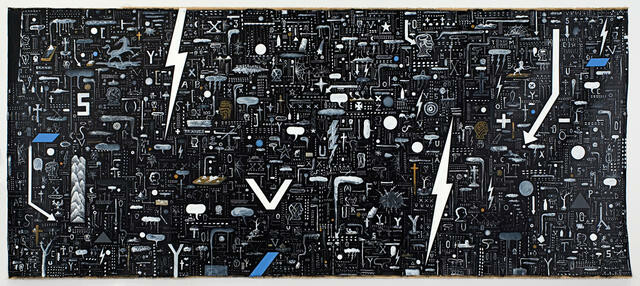

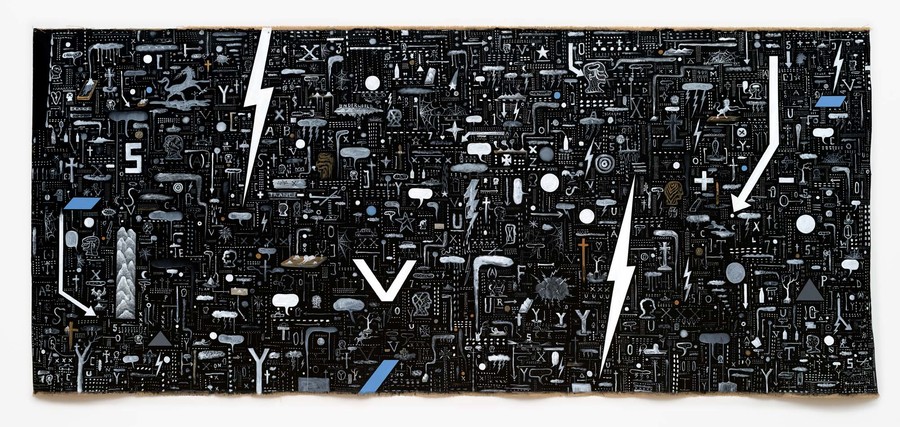

Tony de Lautour Underworld 2 2006. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased by the Friends of Christchurch Art Gallery 2007

Underworld 2 is a must-see. I know, I know. Everything is a must-see or a must-read or a must-do in this society of superlatives and imperatives. But you really do need to be in the same room as this work. Underworld 2 is immense. You need to be in front of it—to be immersed, to be overwhelmed, to be confronted. I start at the left-hand side and plot my journey as if I am planning a road trip and this is my map; first south around the mountains, turn left, then keep going until you pass a lion on the right-hand side. Stop and take in the scenery, go down a dead-end road or two. There’s no rush. You’ll know when you’re there.

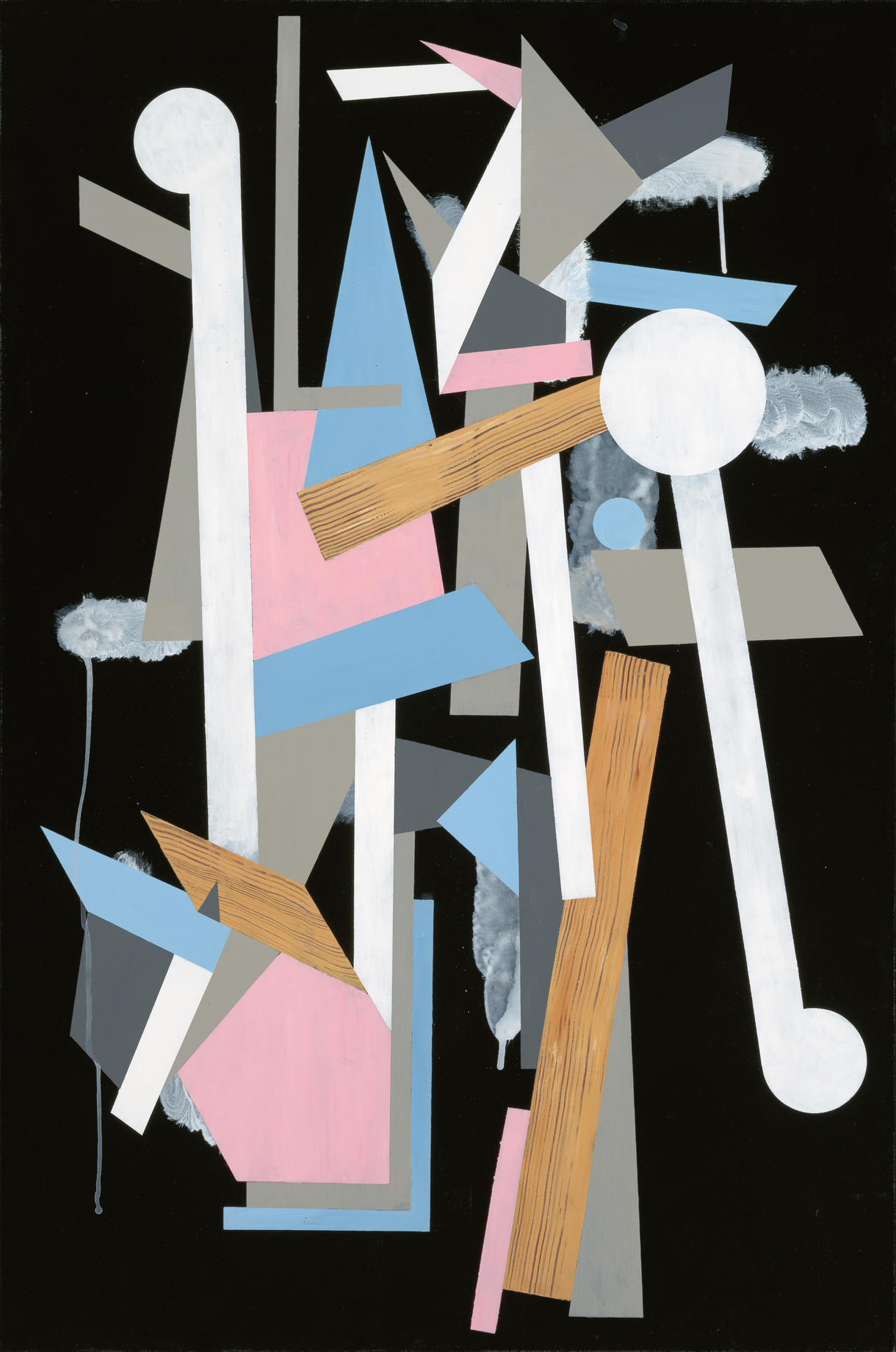

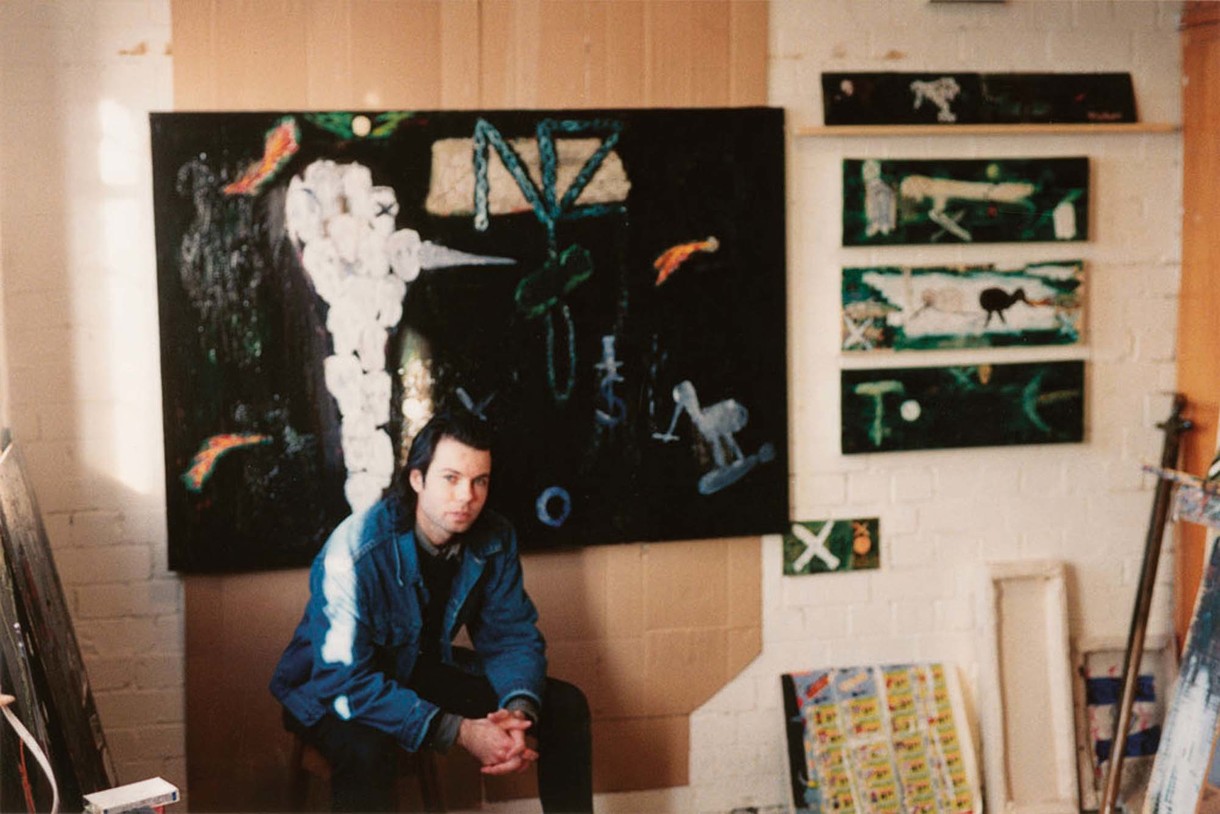

De Lautour is one of the few Christchurch artists to have produced important work both before and after the quakes. While his more recent works have seen his palette include pastels and road-cone orange, this limits itself to chalky whites, spots of blue and some wood panelling. Underworld 2 was completed in a studio that no longer exists, in a city that no longer exists. It is Christchurch before the fall; a dark, grid city, punctuated by order and symbols. Like the city in the decade before the quake, the beauty is in the chaos, the space between; the scenes that don’t feature on the tourist brochures or tacky postcards.

There is rhythm to the randomness—music has always played a strong part in de Lautour’s practice. Phrases from bands such as LCD Soundsystem often materialise in his work. In 2009, the Physics Room hosted a show called b-sides and demos, a tongue-in-cheek reference to the way that some bands will release non-album material. The show shone a light of de Lautour’s process by collecting doodles and sketches that might not usually see the light of day.

I’m not sure what the title Underworld 2 means, but it doesn’t really matter. In a painting that is so packed with imagery, you can find your own. I see the word TRANCE, all caps, streaked as if it were partially erased, and think back to nineties dance music pioneers Underworld. After spending the eighties making guitar music of little interest, they found success by getting rid of the instruments, producing thumping club music laced with lyrics seemingly about nothing: skyscrapers, Walmart, cowbells, fishing vests. But like de Lautour’s painting of the same name, their music is more than just a random collection of symbols and gestures deployed without meaning. There’s a pattern, something to be decoded—and I’ve got no idea what it is. Every time I engage with it, I find a clue that takes me closer to its truth, and another that takes me further away.