Raiding the Minibar

Lara Strongman on a selection of works from Your Hotel Brain

Installation view of Your Hotel Brain, 2017

When does history start? What is the time span of the present? When do the margins of the contemporary begin to dissolve into the past? Our collection-based exhibition, Your Hotel Brain, looks at a group of New Zealand artists who came to prominence in the 1990s. Collectively their work explores ideas that have been critical to art-making in Aotearoa New Zealand over the past twenty years. Identity politics, unreliable autobiographies and references to a broad spectrum of visual culture – including Black Sabbath’s music, prison tattoos, automotive burn-outs and our no-smoking legislation – traverse the contested ground of recent New Zealand art, linking the just-past with the emerging present. A selection of works from the exhibition are reproduced here.

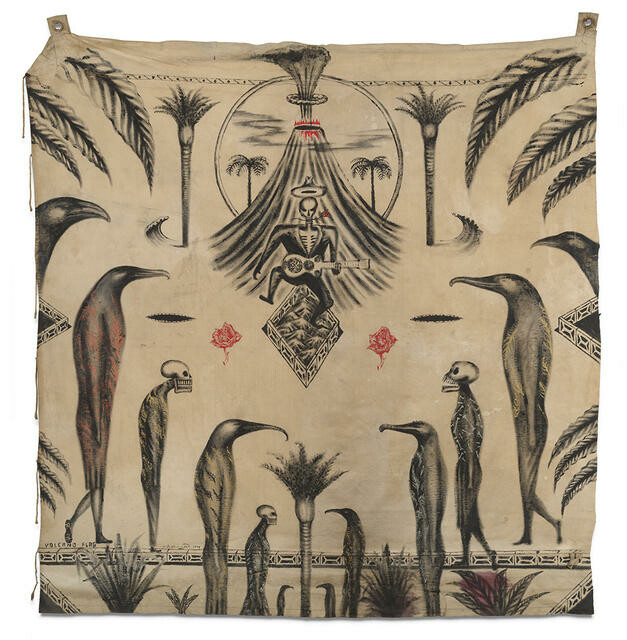

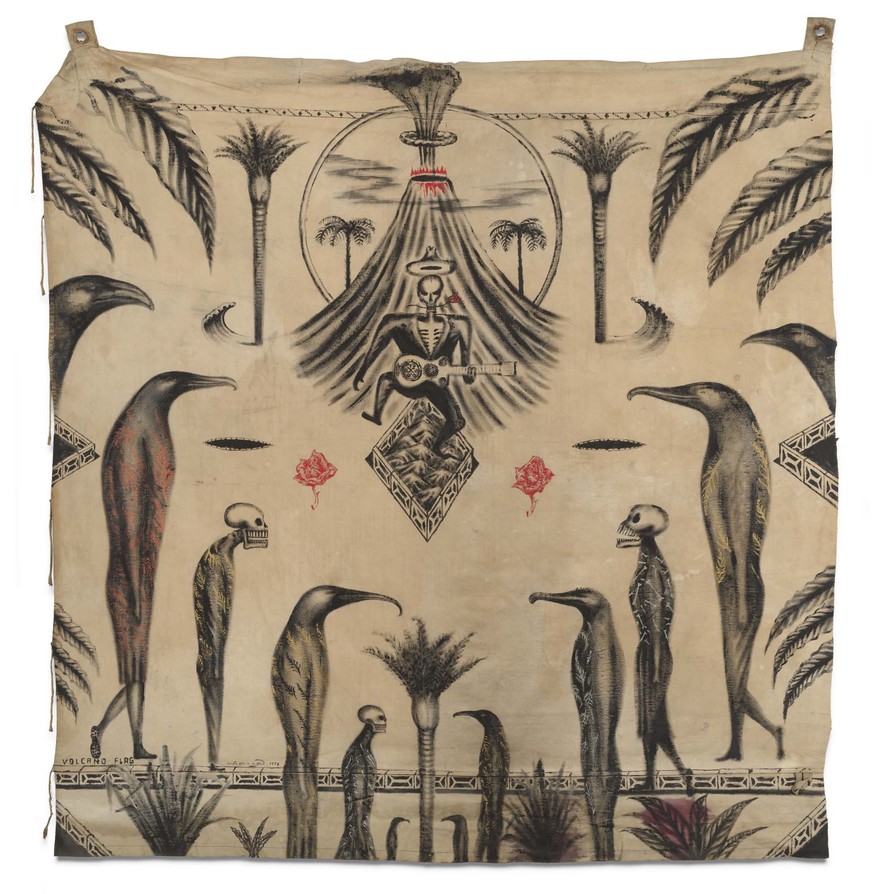

Volcano Flag

Bill Hammond painted Volcano Flag in exchange for a food and beverages tab at Lyttelton’s Volcano Café, later the Lava Bar. It hung there for about fifteen years until the building was demolished following the Christchurch earthquakes of 2010–11. The front window of the café looked out across Lyttelton Harbour, the caldera of a vast extinct volcano, which Hammond has imagined shooting ash plumes and blowing smoke rings.

Hammond’s birds, too, gesture towards a time before human habitation of New Zealand – an environment he had encountered a few years earlier on a trip to the Auckland Islands. ‘It’s bird land. You feel like a time-traveller, as if you have just stumbled upon it – primeval forests, ratas like Walt Disney would make. It’s a beautiful place, but it’s also full of ghosts, shipwrecks, death…’ Different stories, timeframes and images collide in Hammond’s canvases as if in a dream, or as if fragments of consciousness were projected on a screen. ‘I don’t have a tight brief,’ he says. ‘I fumble around history, picking up bits and pieces.’

In the 1980s and 90s he used discarded objects from everyday life – strips of wallpaper, coffee tables and the reverse side of commercial signs – as grounds for his work. He painted Volcano Flag on an old World War I army tent that he found in the basement of his house and left on the washing line for several years to bleach in the sun and rain. ‘I like things that have acquired a patina of time’, he said. Its sister work, Buller’s Table Cloth, which was painted on the other side of the tent, is in the collection of Auckland Art Gallery.

With its square format and dancing skeleton guitarist, Volcano Flag looks a bit like an album cover for an unnamed Southern Gothic band – and points to the distinctive relationship between art, contemporary music and the landscape in the Canterbury region.

Bill Hammond Volcano Flag 1994. Acrylic on canvas tent. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2016

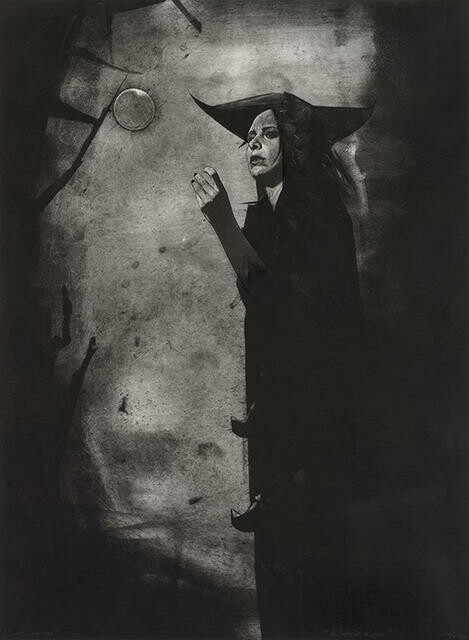

Vulcan paradise, An orbital thought, Blood is thicker, The Malcontent, Depth charge and Walt’s wet dream

Back in the 1990s, Jason Greig famously said that heavy metal band Black Sabbath was the thing that got him up and going and wanting to draw. It’s a line that’s often been quoted in relation to his work, probably because it seems to be at odds with the refinement and virtuosity of his printmaking technique, or the venerable tradition of artists in which he works – Redon, Goya and Piranesi. Greig, however, said that Black Sabbath’s music was fuel: ‘the imagery and the weight of it … I do heavy, laden drawings, dense. When I hear some really loud guitars it gives me the same sort of feeling.’

The images collected here span nearly two decades and reveal a remarkably consistent imagination, forged in Greig’s reading of nineteenth-century Gothic novelists such as Mary Shelley and Edgar Allan Poe, and what he describes as the ‘battle of good and evil’ in mid-twentieth-century movies. Light falls across blasted volcanic landscapes; isolated figures clutch books or brandish scythes; sinister deals of one sort or another appear to be in the process of playing out. The corners of most of the images are dark, vignetted like an early photograph. For Greig, the past is full of unfinished business. ‘I guess it’s about wearing your lineage on your sleeve. I reckon that images of last century are catching up with this.’

Greig’s figures are versions of himself, ‘but I try to disguise it a bit’. They evoke psychological states of alienation and estrangement, and depict life as a long strange journey into the unknown. ‘My art is about love; lost and found. It’s about dark lonely places; imagined and real. And it’s about the constant naggin’ thought that the end is always nearer. I have dealt with my demons, in life and on pieces of pummelled paper. The road I have travelled has been paved with gold that shines, and with bile that fumes.’

Clockwise from left:

Jason Greig Vulcan paradise 1998. Monoprint. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1998

Jason Greig An orbital thought 1993–2014. Monoprint. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of June Vialls Goldstein 2015 in memory of her grandson Louis Cooke 1993–2014

Jason Greig Blood is thicker 2005. Monoprint. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2005

Jason Greig The Malcontent 1993. Monoprint. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1993

Jason Greig Depth charge 2005. Monoprint. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2005

Jason Greig Walt’s wet dream 2012. Monoprint. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2012

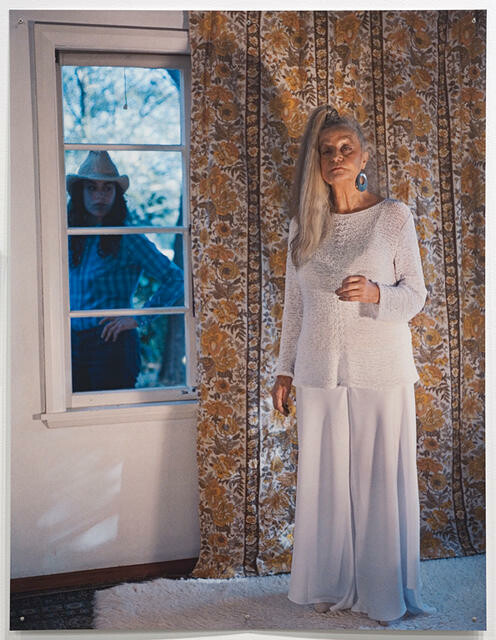

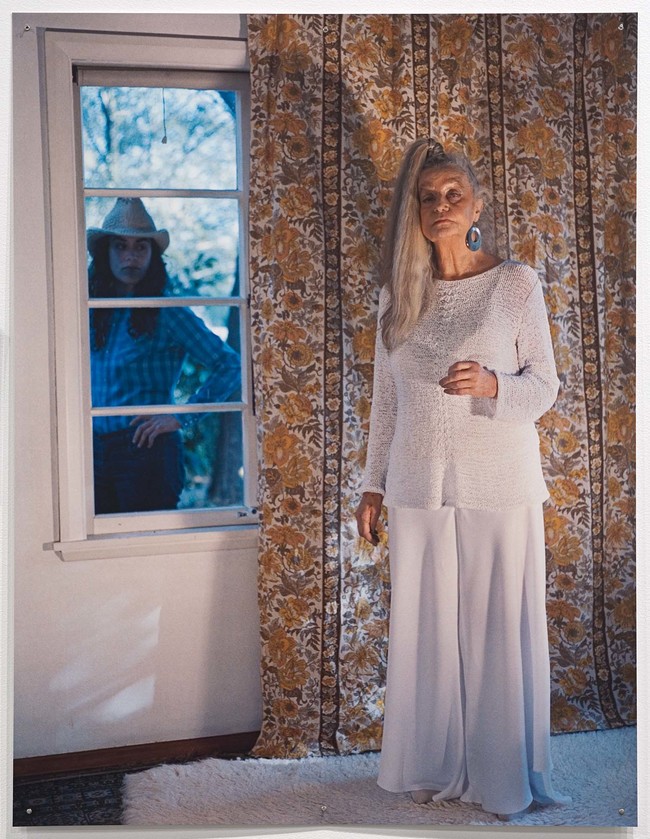

Marg n.l. Persona and Hobbyhorse (outside)

Margaret Dawson Marg n.l. Persona 1987. C-type print. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1988

Margaret Dawson took several attempts to make Marg n.l. Persona over a series of evenings. She’d made drawings of how she envisaged the photograph to act as a guide; she wanted the broken sunlight on the weatherboards to reflect similar patterns as the leopard-skin coat she’d found in an op shop; she needed to wrangle the cats. (The white one, Eve, was named after the artist Evelyn Page: Dawson rescued her from outside the Robert McDougall Art Gallery.) When she’d got all of the elements in place, Dawson checked the composition with a Polaroid then assumed her position. A flatmate pressed the button on her camera.

Marg n.l. Persona is a self-portrait that is also a fiction, gesturing towards the idea, perhaps, that all selves are essentially constructions. ‘It seemed natural to use myself as an actor,’ said Dawson, ‘showing how one can move into a role, and out…’ It took a lot of work to appear so casual. The photograph looks like a snapshot – a suburban woman looking after her cats, pictured in the doorway of her house one early evening, not doing anything particularly special – but the large scale of the print gives her actions a significance that compels attention. ‘I work intuitively as a feminist,’ Dawson noted at the time. ‘My work has changed from observing with a camera (recording) to examining behaviour, acts for life.’

Hobbyhorse (outside) was made eighteen years later: the setting, again, was Dawson’s weatherboard house. It’s one of a series of works concerned with ideas of playfulness. ‘I was playing with representations of women of various ages. Both of these women had their own distinctive style regardless of latest fashion. Although I didn’t know them well I admired their self-confidence. I asked one to select lighter clothes from her wardrobe and the other darker. Positioning one woman outside the other inside created a mystery, a tension – and suggested a story in the image, although mine might be a different one from the next viewer’s.’

Dawson’s aim, in both images, was to achieve a female gaze – meaning that she was keen to establish a female perspective for both the production and reception of the image. ‘There are always problems,’ she’s said, ‘with putting representations of women in the picture.’ A heterosexual male gaze is the default perspective of advertising and the mass media, in which a woman becomes a spectacle to be looked at, and is judged on her age and appearance. Dawson’s photographs subvert this convention, training her gaze on the unspectacular everyday lives of women.

Margaret Dawson Hobbyhorse (outside) 2005. C-type print. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2005

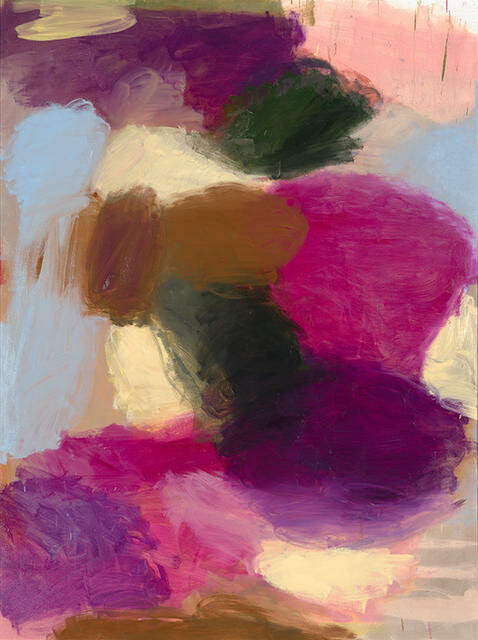

In a lonely place

In a lonely place is the title of a classic film noir directed by Nicholas Ray, who was best known for the counterculture movie that starred James Dean in his most celebrated role, Rebel Without A Cause. When Robin Neate was titling this work – which comes from a series he called the Ray Paintings – he chose the phrase for its evocative feeling and ability to provoke personal readings from the viewer. ‘In a lonely place. I’ve been thinking maybe that’s where painting is today; but at the time that I chose it I was thinking more about the loneliness of working in your studio or even living in this part of the world.’

The Ray Paintings continue Neate’s earlier explorations of abstraction in photographs and experimental films. ‘Cinema has influenced me as much as painting,’ he says. ‘Growing up in New Zealand, cinema gave you ideas from the wider world that might resonate with you.’ Falls of light in darkened rooms, clouds of dust in a projector beam, the blur of an out-of-focus image; Neate’s abstract paintings recall long afternoons spent in movie theatre matinees during the 1950s and 1960s while other kids were outside playing sport. ‘The way we see history is always linked to our personal histories. How and when we encounter images is always significant. It’s that emotional context for art that interests me the most.’

Neate’s works reveal a concern for the discarded and outmoded: painting, he suggests, is not a linear practice but one filled with loops and double-backs, whose history – along with the wider register of visual culture – is instantly available as source material for a contemporary artist.

Robin Neate In a lonely place 2013. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2016

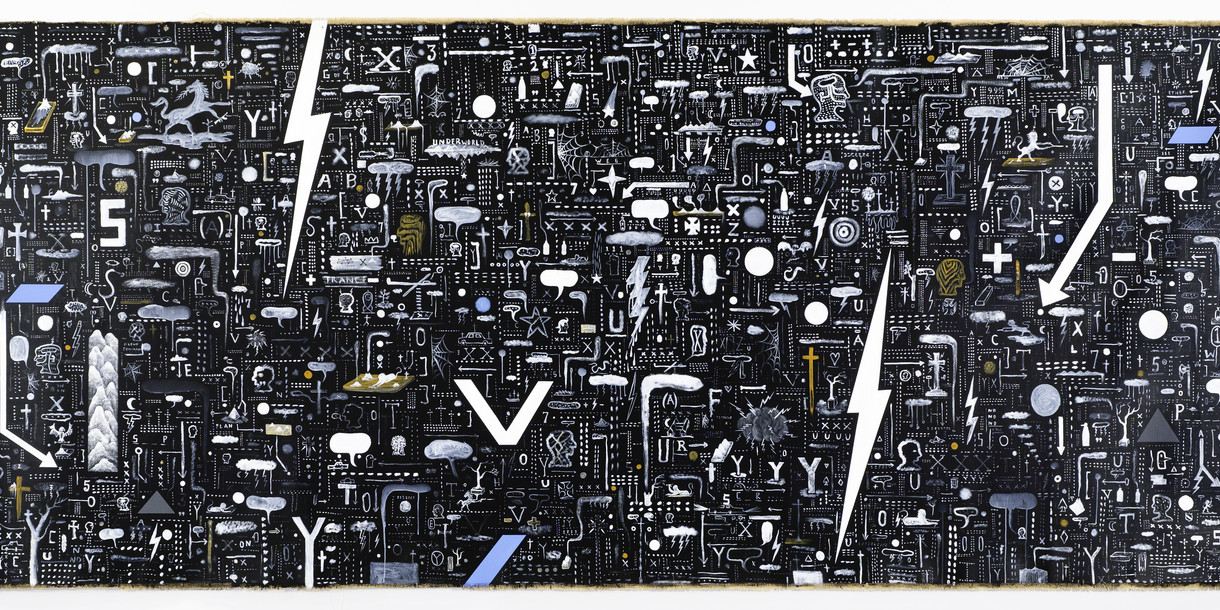

Untitled

Over the years, Séraphine Pick has collected a large personal archive of images, which she uses as the starting point for her paintings. Recently, she’s been working with images she’s found online – but in 1997 when she painted Untitled, she was still largely using analogue images. Clippings. Bits of paper. Things torn out of magazines. Stills from movies, or pornographic photos. And images that she drew from memory or experienced in dreams.

Untitled is from a series sometimes referred to as Pick’s blackboard paintings. Produced after she returned from Europe in 1995–6, they signalled a shift in her practice away from her more confessional works of the early 1990s, where she created a series of talismanic objects inspired by memories of her childhood experiences. Like her other blackboard paintings, Untitled is full of revisions and erasures, where forms are variously painted in and rubbed out, as if Pick had changed her mind part way through. Some figures have been given weight and mass while others are scratched in with the wrong end of the paint brush. At the bottom of the painting, an electric jug is boiling – it’s as if the figures above are writhing in clouds of steam, forming themselves out of fog. There’s no horizon line: rather than a landscape, this is a dreamscape, an unbounded weightless space in which everything is happening all at once and everything needs to be considered in relation to everything else.

Pick’s earlier works were widely understood to be autobiographical, but she strongly repudiated that at the time. ‘The autobiographical is not literal,’ she has said, firmly. With their looser handling, and surrealistic scenarios, Untitled and other works from this period made it clear that Pick’s bigger project was a consideration of the way that we imagine ourselves into being. Dreams, experiences, memories and found images combine and recombine in Pick’s painting – and in the subconscious of the individual – to produce a self which is always in the process of becoming something, or someone, else.

Séraphine Pick Untitled 1998. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1998