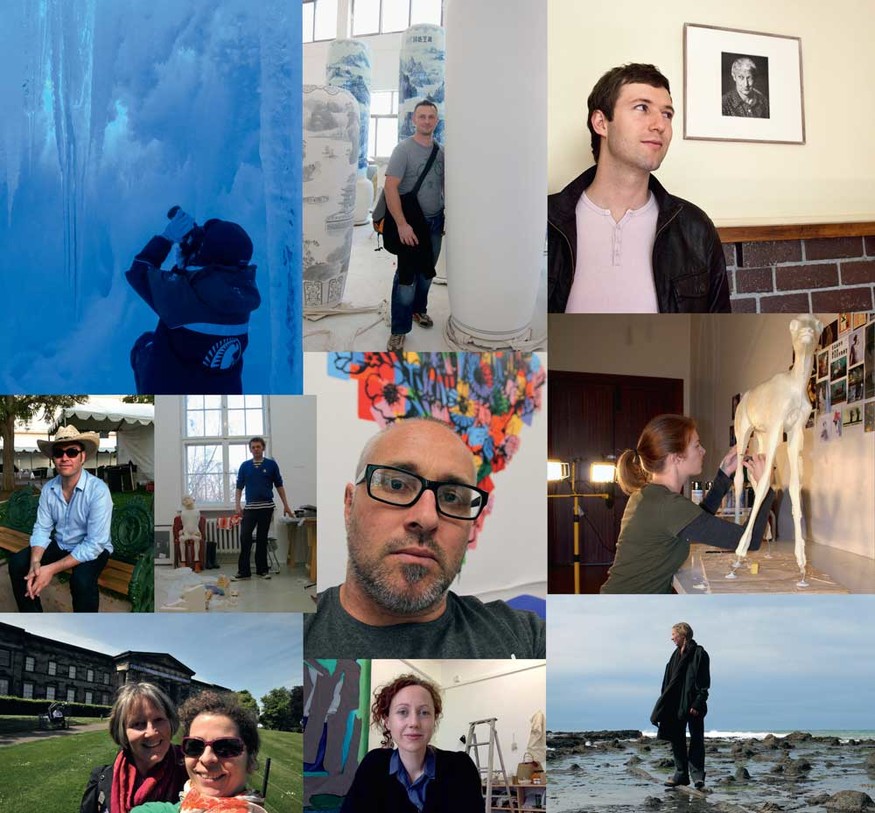

Shigeyuki Kihara, Samoa Artist-In-Residence Programme, Apia. Photo: Leuli Eshraghi; Jae Hoon Lee, Cemeti Art House Residency, Indonesia; Reuben Paterson, Goyang Art Studio Residency, South Korea; Cheryl Lucas, FuLe International Ceramics Museum, Fuping, China; Andrew Drummond, Artbarns Project via Lancashire County Council, Wycoller, England; Séraphine Pick, Olivia Spencer Bower Fellowship, Christchurch. Photo: Luke Strongman; Michael Reed, Nagasawa Art Park Artist-in-Residence Programme, Japan; Chris Pole, Shalini Ganendra Fine Art Culture Residency, Malaysia; Ben Cauchi, CNZ Visual Arts Residency, Berlin; Sara Hughes, CNZ Visual Arts Residency, Berlin

A Room of One’s Own

That experience of foreignness, of working within a different geographic or cultural context, has proved a compelling stimulus for arts practices, particularly when coupled with a studio and free accommodation.

As you read this, hundreds of artists and curators from around the world are carving out a living and working space in locations made remarkable by their strangeness and/or the opportunity to live and work away from the pressure of paid work, be it in Sweden or Southland, Dunedin or Denmark, New Plymouth or the Netherlands.

'There is no foreign land,' wrote Robert Louis Stevenson. 'It is the traveller only that is foreign.'1

For Auckland artist Reuben Paterson, a recently completed three-month residency at the Goyang Art Studio in South Korea was an invaluable opportunity to immerse himself in 'something different':

'To see, taste and experience something new. Residencies are great for this because they give you a longer opportunity to be involved in a culture and to come closer to the truth of it, to have that experience of another place and another time and see how those experiences translate back into your work.'

The Goyang Art Studio residency is one of seven offered through the Asia New Zealand Foundation (ANZF) to help New Zealand artists further their careers and gain an understanding of contemporary art in South Korea, India, Malaysia, Taiwan and, from next year, Thailand, Vietnam and Japan.

'The overarching goal [for the Foundation] is to develop New Zealand knowledge and understanding of Asia,' says ANZF project officer culture, Monica Turner:

'It is about giving visiting artists a good working knowledge of arts practice in Asia—building networks, making connections—while also giving Asian artists the opportunity to work with international artists. One of our hopes is that New Zealand artists will come back here and share their experience with other artists, through something being published or an exhibition. It is cultural diplomacy really.'

The ANZF is one of several national or international organisations supported by Creative New Zealand through its annual contestable funding rounds and special opportunities portfolio. For visual artists the latter includes the three-month International Studio and Curatorial Program (ISCP) in New York and the biennial Creative New Zealand Visual Arts Residency in Berlin, currently held by New Zealand/Samoan artist Greg Semu. Both, says Raewyn Bright, CNZ manager of arts grants and creative communities schemes, are reputable residencies that allow New Zealand artists to further their careers on an international stage.

One of the goals of such opportunities, she says, is to 'provide a platform for artists to fly in terms of international opportunity and professional development, to have that chance for international exposure so they can produce and interact globally as well as nationally. We live in a global arts community and the networks they forge endure for a long term.'

She points to previous recipients of the Berlin residency: Peter Robinson, Ronnie van Hout, Michael Stevenson, Sara Hughes and Simon Denny (who will represent New Zealand at next year's Venice Biennale).

'When you think about the track record of those people, the outcomes have been extraordinary and we take some pride in supporting them at various stages in their career.'

The ISCP residency in an imposing 1901 building in Brooklyn, New York, is similarly embedded within a wider arts programme. Awardees are taken on field trips and museum and gallery visits; they are introduced to other artists and given the opportunity to host critics in their studio.

For current ISCP resident Jae Hoon Lee the very experience of travel, of moving from place to place, is fundamental to his practice.

'My work is focused on documentation,' he says on the phone from New York, 'about me being in a different location within a different culture and a different landscape, engaging with this new environment to collect source material and to pick up on the experience of being an Asian male, 40 years old, moving from one place to another.

'It is very personal but I also want to neutralise this process so other people can engage with that moment I experience in such a location.'

Hannah Beehre, Artists to Antarctica Programme; Gregor Kregar, Pottery Workshop Residency, Jingdezhen, China; André Hemer, Rita Angus Residency, Wellington; Nathan Pohio, Santa Fe Art Institute International Artists and Writers Residency Program; Ronnie van Hout, CNZ Visual Arts Residency, Berlin; Wayne Youle, SCAPE Christchurch/Artspace Sydney Artist Residency; Cat Auburn, Olivia Spencer Bower Fellowship, Christchurch; Edwards + Johann, Perth Museum and Art Gallery Artists in Residence, Scotland; Emma Fitts, Olivia Spencer Bower Fellowship, Christchurch; Miranda Parkes, William Hodges Fellowship Artist-in-Residence Programme, Invercargill

Not all opportunities to engage with a new community, to live and work outside the requirements of a workaday income, require a boarding pass. In New Zealand's four main cities and in towns across the country, trusts, universities and galleries have established awards that allow emerging and—unfortunately not so frequently—mid-career artists to focus almost entirely on their work.

Before going to South Korea, Paterson was artist in residence at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery in New Plymouth. This residency resulted in the remarkable The Golden Bearing, a 4.5-metre gold-glittered tree installed temporarily at Pukekura Park.

'In Korea you had to start from scratch whereas [in New Plymouth] it was a very clear conversation. You don't have challenges like language so you have more time to focus on the work and make relationships. Everything just fell into place. I quickly knew what I wanted to make and I felt very much part of the community.'

Artists can spend six months in the august Burwell House in Invercargill under the William Hodges Fellowship Artist-in-Residence Programme, named after the official artist on James Cook's second voyage to the Pacific, employed, in Cook's words, 'to make drawings and paintings of such places in the countries we should touch at, as might be proper to give a more perfect idea thereof, than could be formed from written descriptions only'.2

They can spend four to six months at the Tylee Cottage Artist-in-Residence programme in Whanganui, launched in 1986 and counting Laurence Aberhart, Andrew Drummond, Anne Noble, Peter Ireland, Gregor Kregar, Christine Hellyar, Paul Johns, Ben Cauchi, Matt Couper, Mark Braunias, Joanna Langford, Regan Gentry, James Robinson, Miranda Parkes and, most recently, Auckland-based mixed-media artist Richard Orjis amongst its participants.

They can spend three months at the McCahon House Artists' Residency in French Bay, Titirangi, living and working in a purpose-built residence and studio next to McCahon's former home; three-months at the CNZ Macmillan Brown Pacific Artist-in-Residence Programme at the University of Canterbury; or three months—or thereabouts—using the studio at the 30 Upstairs gallery space in Wellington's Courtenay Place.

Many of these residencies are dedicated solely to furthering an artist's career. Writing in 1959, Landfall editor Charles Brasch claimed it was part of a university's 'proper business' to act as 'nurse to the arts, or, more exactly, to the imagination as it expresses itself in the arts and sciences.'3 Three years later the University of Otago Council established the Frances Hodgkins Fellowship, now one of five arts residencies offered by the university, and currently held by Patrick Lundberg.

In Christchurch the Olivia Spencer Bower Foundation Art Award is unique in being established and defined by the artist whose name it bears and being entirely funded from the proceeds of her bequest. The year-long $30,000 residency is aimed at supporting the artistic potential of painters and sculptors living in or associated with Canterbury. While the Canterbury earthquakes temporarily closed the Award's studio space in the Christchurch Arts Centre, this year's recipient, Emma Fitts, has the use of a studio in the Physics Room.

Others residencies are more didactic in purpose. The Artists to Antarctica Programme run by Antarctica New Zealand, due to be reinstated in the 2015–16 season, aims to increase understanding of the white continent through the contribution of visual artists, designers, choreographers, composers and writers. Dating back to early visits by war artist Peter McIntyre (1957 and 1959) and RNZAF official artist Maurice Conly (1970) and launched in 1997 with visits by poet Bill Manhire, painter Nigel Brown and writer Chris Orsman, the programme, says Antarctica New Zealand CEO Peter Begg, is an 'important outreach opportunity', providing education 'as to what we do and why we do it'.

'We need people to understand what Antarctica is teaching us, not in the specifics of science but in how it affects New Zealand in terms of climate or fish on a plate or lichen that might affect our medicine. So we are looking for people to support that message and the arts programme is part of that.'

As part of 'good governance', says Begg, there needs to be identifiable outcomes: 'We are spending a lot of taxpayers' money to send someone to Antarctica, I need to say what we are getting for our money.' Harder to quantify but equally important is the extent to which artists such as photographers Anne Noble and Megan Jenkinson, sound artist Phil Dadson, painters and printmakers Kathryn Madill and Denise Copland have succeeded in embedding the frozen continent in our collective imagination.

Alejandro Haiek-Coll and GapFiller Instant public space; pop-up grandstand outside the demolition of Centennial Pool 14 July 2014

Near or far, three weeks or three months, residencies do have their challenges. While many hosts go out of their way to welcome visiting artists and introduce them to local artists and curators, for some these experiences can be lonely. They can be cold. They can be simply daunting.

Jae Hoon Lee recalls his seven-day tenure in Antarctica. 'It was all so new and in the first two days at Scott Base I felt quite disoriented. Most of the people—biologists, meteorologists—were doing their own work. I was just this Asian guy with a camera, like a tourist, an outsider. But my schedule was free—I could do what I wanted.'

For artists travelling to an Asian country for the first time, says Turner, a residency is a life-changing experience.

'They have ideas about what it is like and what is going to happen and a lot of these ideas get completely blown out of the water. And it can be hard. Going to live in a foreign country that you have never been to, you can't speak the language, you don't know where anything is—there is a level of that free-spirited sense of adventure and self-sufficiency, but a degree of homesickness and culture shock is quite normal.'

Paterson remembers his arrival in South Korea: 'It took two weeks to find out where to buy coat hangers. The studio, shared with twenty-one other artists, was an hour and half out of Seoul in a forest not far from the DMZ, and conversing in second languages means you are only ever having half a conversation.'

But these challenges, he says, help you direct your own discovery of the place. 'It makes for a struggle but it is that struggle that will make it really interesting.'

It is from such challenges, says Samoan-born interdisciplinary artist Shigeyuki Kihara, that great art emerges. Kihara is currently in Apia for a three-month residency funded by the National University of Samoa and CNZ to give Pasifika artists in New Zealand the opportunity to develop their practice. Recipients are expected to run workshops or mentor young artists, deliver a presentation and complete a full written report—requirements well-suited to Kihara's goals as an artist and curator.

'In New Zealand there is the idea that contemporary Samoan art exists only in diaspora, that contemporary art in Samoa is all customary based—house-building, stone-carving, boat-building, siapo-making and so on. But when you live here and engage with the people you see many more working in a variety of different media. This is where I wear my curator hat, looking at the current climate for contemporary art in Samoa and working towards an exhibition of contemporary art in and from Samoa. I am not treating this as one of those residencies where you go in and out. I am going there with the hope to establish relationships with the local arts community.'

For Kihara this level of engagement, this involvement in an 'international conversation', is essential to a successful residency.

'Residencies where an artist is given the key to a studio and left to do their own thing can be so isolating. That is not how I work. My practice is very interactive and socially engaged; every residency wherever I go I want to plug into the system, be part of the arts system of the place.'

There is an ambassadorial aspect to many of these international residencies too, as artists present their work within the context of New Zealand art. Kihara's goals for her residency are to re-integrate herself back into Samoa's arts community and also to act as a conduit for information on Pacific art practices in New Zealand.

'Many artists of Samoan descent in New Zealand—writers, poets, choreographers and visual artists—make work that points to Samoa. I want to disseminate some of that information back into Samoa.'

As an artist working within an international arts community, there will, agrees Paterson, inevitably be an element of 'speaking on behalf of' the arts in this country.

'We help others understand that New Zealand is not a country based solely on its sporting credentials, that it has a rich intellectual and creative side. One person can't be reflective of a whole country but one person can intrigue others about the country. People in Seoul knew New Zealand is a beautiful country but they became curious about other things.'

Such as the bizarre urban landscape that is present-day Christchurch. Earlier this year Venezuelan artist and architect Alejandro Haiek Coll, in New Zealand as part of the Elam International Artist-in-Residence Programme, became the inaugural recipient of a new residency at the Physics Room, through which the inner-city project space hopes to work in partnership with other institutions around the country to offer temporary accommodation and studio space to visiting artists. During his stay Coll worked with the Festival of Transitional Architecture and Gap Filler in responding to the ongoing demolitions and the rapidly changing landscape that is Christchurch.

'Responding to the environment and working with the community are really good goals for Christchurch,' says Physics Room director Melanie Oliver. 'We host [visiting artists] in an organised way—we have a welcome, a public talk, take them out to art school and let students have some of that fresh input and energy. I'm keen too on having open studios so people can see what the artist is working on. It's not outcome-based—it doesn't have to result in an exhibition—but they do become part of the Physics Room community for a while.'

The most effective residencies, agrees newly appointed senior curator at Christchurch Art Gallery Lara Strongman, keep expectations to a minimum.

'Often a residency will have an end goal, an exhibition or the production of work. That can put huge pressure on the artist. Ideas have all sorts of different lengths of gestation—residencies often work two or three years down the track, when people have had time to assimilate what they have learned and seen in the new environment.'

Strongman is keen to see the establishment of another new residency to refresh and challenge Christchurch's art scene.

'The situation in Christchurch is difficult but incredibly interesting. To make a virtue out of that interestingness a strong residency programme, bringing people in from outside, would be really good for the arts locally and provide an extraordinary context for people from outside the city to make art. And it has that secondary benefit of promoting the city as a cultural place more broadly.'

Sending an artist to a different place, to work or simply experience that place, is a percipient use of public or private funds. Whatever the foundational goal, be it cultural diplomacy, new art encounters or a room of one's own without the requirements of paid work, such residencies speak of a belief in the ability of artists, given time, space and a period of economic independence, to explore strangeness, to engage with other art practices and to filter these experiences back to the wider community in unique and divergent ways.