Drawing from Life

Glen Hayward I don't want you to worry about me, I have met some Beautiful People 2012–13. Wood and paint. Installation view, City Gallery Wellington 2013. Courtesy of the artist and Starkwhite, Auckland. Photo: Hamish McLaren

In the beginning art was drawing.

When I was a teenager I threw a shoe across the lounge and it smashed Mum's favourite ornament: a terracotta church she'd bought at Trade Aid. I sent the shoe on this swift shocking voyage because I couldn't draw properly. I longed to be as good as Kent, the best drawer in my art class. Kent's pictures of Māori carvings were nuanced studies of photorealism rendered in oil pastels. The paua shell eyes in his pictures shone as though still lit by the flattering lights of a shop window display. I grew up in Rotorua. Above our heads in the art room, pictures of heavily impasto mud pools were pegged up to dry. I always had to make up for my lack of skill with colour, pizzazz, plops of paint.

My original understanding of art was founded on technique. To be able to draw accurately from life was a prerequisite. High school art history was my introduction to a wider point of view. I quickly crossed the bridge over Monet's pond of dappled water lilies and found modern art waiting on the other side. Tawny Cubism strutted its stuff with self-importance. Duchamp's nude descended a staircase, her hips like a violin split open; her legs the black staccato strings. I discovered that Picasso's blue phase painting of the Madonna and Child was not just a depressing print Mum got from the Salvation Army – it was the early work of a twentieth-century master. Who knew? Our teacher explained that Picasso was free to break the rules, because he was already a good drawer. Picasso's voyage from representation to cubism was as pronounced as the arc of my school shoe.

Art became a hot idea: Andy Warhol's white wig, a lightbulb switched on. Art could be produced by the hive, in the factory. All I needed was the assistance to make it happen or the cash to buy a readymade; R. Mutt's fountain; Christo's wrapped monuments; Billy Apple's apple. In the early nineties I studied at Elam. I shunned technique and the hand-held properties of drawing. Craft was earnest and earnest was uncool. I was free. As an artist I didn't have to be a good drawer. I didn't even have to be original.

Escape is – of course – just another form of illusion.

The clock winds back.

The table is set for a seafood feast. Fish slide head first from an overturned bucket. A crayfish lies on a plate, its tail hunched over its belly. A lemon sits on the brink of the table, half peeled; its skin twists over the edge in a spiral. Killing Time is a life-size carving made out of a pale hardwood. Ricky Swallow's epic sculpture is a still life, a memento mori to his father, a fisherman, and the catches the family once ate together. I first saw Killing Time in the Australian pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2005. The work satiated some part of me that hungers for craft. I still have that need to marvel at an artwork closely drawn from life. Swallow paid such tender attention to the tablecloth. It lies crinkled across one corner of the table, the bucket caught in its folds. Drapery was of paramount importance in art class. I spent hours shading-in curtains, trying to conjure the illusion that you could wrap yourself inside the pleats. Kent could have drawn a superb oil pastel of Killing Time. Like Swallow, he knew how to inspire incredulity.

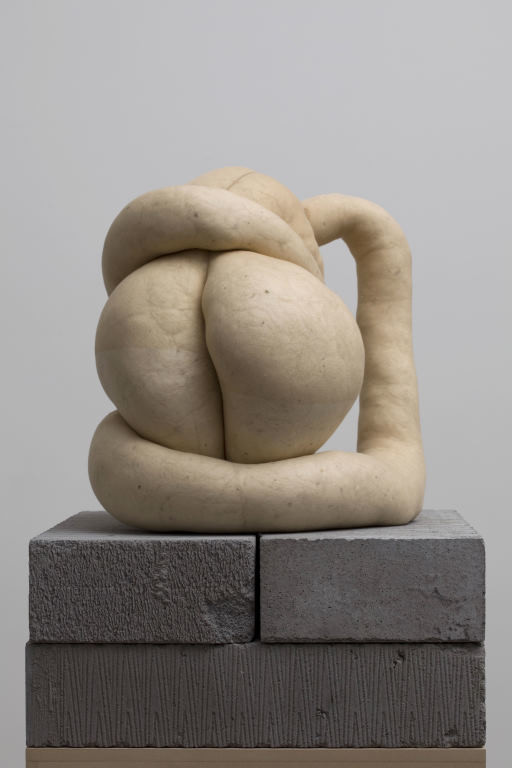

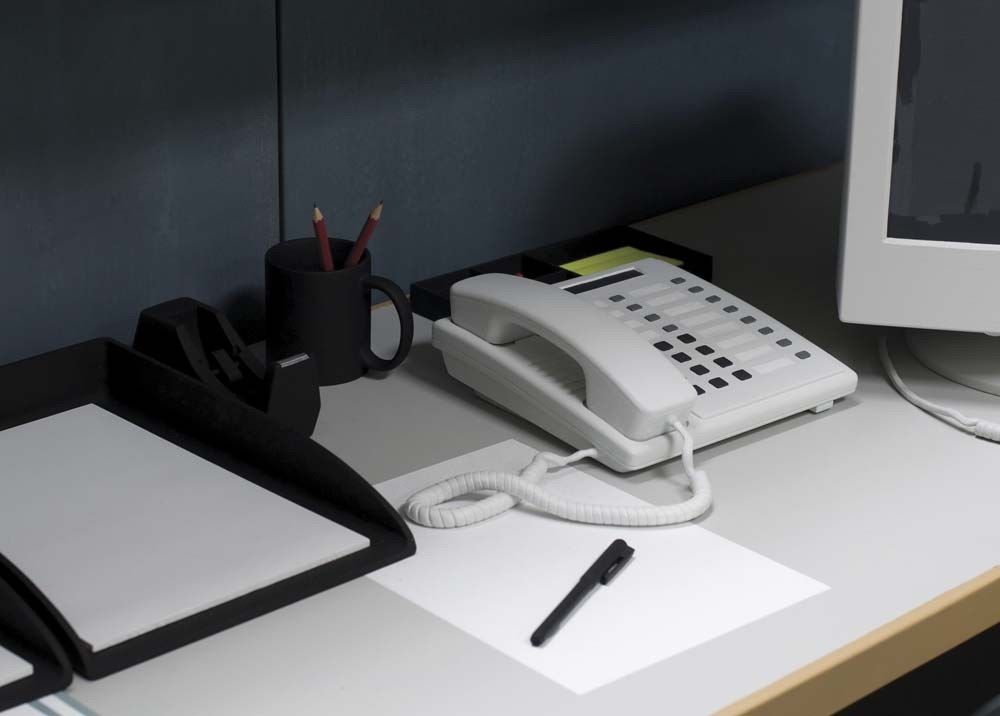

My idea of what drawing can be has expanded, but I've always maintained a love of representational work. I recently saw a replica of an office cubicle created out of wood. This sculpture sat moored in the middle of a white room upstairs at City Gallery Wellington. Above the wooden computer was a standard grey office cupboard. The swivel chair at the desk acts as a decoy. I don't want you to worry about me, I have met some Beautiful People by Glen Hayward exists in the space between technology and the handcrafted. I didn't recognise the office as Neo's cubicle from The Matrix, but I knew I was looking at an experience of simulacra. As in the film, appearances are not what they seem. Hayward's office is a fabrication, an imposter, a dummy. The Matrix is about ruptured reality: beneath the surface of the representational world we are all controlled by machines. In our increasingly mediated world it's a fiction that's easy to believe.

Like Neo, my perspective of reality has shifted. Navigating the coded world of contemporary art is a mind-altering journey, yet somehow I always return to the traditional values: illusion, craft, technique.

Re. the church from Trade Aid: Mum managed to glue it back together, but the cracks still show. I've never thrown a shoe across the lounge again. Then again, I've also stopped drawing.

Glen Hayward I don't want you to worry about me, I have met some Beautiful People 2012–13. Wood and paint. Installation view, City Gallery Wellington 2013. Courtesy of the artist and Starkwhite, Auckland. Photo: Hamish McLaren

Glen Hayward I don't want you to worry about me, I have met some Beautiful People 2012–13. Wood and paint. Installation view, City Gallery Wellington 2013. Courtesy of the artist and Starkwhite, Auckland. Photo: Hamish McLaren