B.

Mauria mai, tono ano by Fiona Pardington

Collection

This article first appeared in The Press on 11 May 2005

Fiona Pardington Mauria mai, tono ano 2001. Photographs. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2001. Reproduced with permission

Art has always been more than just a career choice for Fiona Pardington. Instead, she describes it as 'compulsory' and she has long used photography as means of understanding and expressing the world around her. A glance back over more than twenty years of practice reveals a resolute and intensive investigation of the powers and limitations of the camera: those things it fails to capture, but also what it is able to suggest.

Although she entered Auckland's Elam School of Fine Arts in the early 1980s as a Painting student, Pardington soon made the shift to photography after seeing the images produced by contemporaries such as Anne Noble. Her early works concentrated on the representation of the body and the role of the artist and photographer in gender politics. In particular, a series of fetishistic male nudes posed a challenge to the long artistic and erotic traditions of female objectification.

In the mid-1990s the discovery of a set of proof sheets for erotic black and white images of women, taken by an unknown photographer in the 1950s and 1960s, led Pardington to re-present these intimate and highly personal portraits within a gallery context. Viewing them there was a troubling and voyeuristic experience, bringing issues of privacy, access and exploitation to the surface. Such subversions of viewer expectations were to become a distinctive motif in Pardington's work, as she sought to breathe new life into appropriated and stereotypical objects and images.

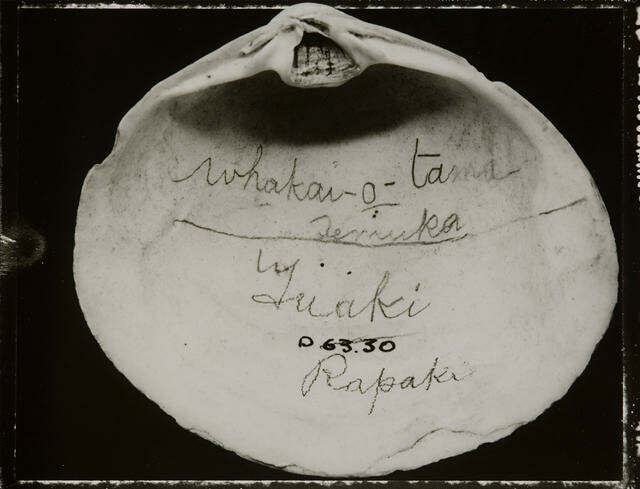

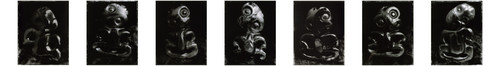

Mauria mai, tono ano (literally ‘to bring to light, to claim again') is a remarkable grouping of seven large-scale silver gelatin photographs depicting heitiki, or greenstone pendants.The heitiki themselves are held in the collection of the Auckland Museum, but all came originally from the South Island and they are all connected to Pardington's own Ngai Tahu iwi. Traditionally worn close to the heart, heitiki are sacred to Maori as symbols of fertility and invested with great spiritual significance. Working within the tradition of the photographic still life, it was Pardington's intention not only to record the physical attributes of these old and precious objects, but also to capture some of their more intangible qualities, such as the powerful sense of connection to the past that can send a shiver down your spine when encountering the personal effects of a distant ancestor.

Like much of Pardington's work, the deceptively simple and disarmingly beautiful heitiki in Mauria mai, tono ano challenge the context in which they are viewed. Prized by early explorers and collected by museums throughout the world, heitiki quickly became iconic New Zealand objects, and were later appropriated for advertising and fashion. Printed on a fibre-based paper that seems to bring out the light from within the well-worn greenstone, Pardington's images inhabit a territory somewhere between present and past, confronting us directly in the here and now, yet never losing their association with times and people gone by. This isn't flashy photography, captured and absorbed in a moment: Pardington's forté is the art of the slow burn.

Felicity Milburn