B.

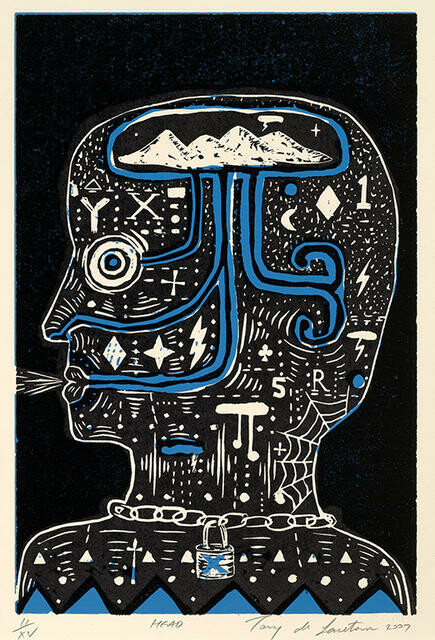

Head by Tony de Lautour

Collection

This article first appeared as 'Crackle, buzz and hum' in The Press on 28 June 2013

Some works in the Gallery's collection are classic loudmouths, brashly seizing our attention or demanding a response. Others are strong and silent types, the kind visitors gather around in a reflective, even reverential, hush. Falling somewhere between those extremes is Head, a modestly sized, highly charged woodcut by Christchurch artist Tony de Lautour that doesn't so much speak as crackle, buzz and hum.

Against a dark background, an unbroken white line demarcates a human profile and seals off a dazzling circuit, crowded with marks, signs and symbols. At the top of this head – where we might expect to find the brain, or perhaps the mind's eye – is a second space, outlined in cerulean blue and containing, incongruously, a mountain range. A series of blue channels runs from this mindscape to the target-shaped eye, the curled koru of the ear, the nose, and down to the lips, from which white lines are propelled forcefully outwards in indecipherable expectorations. De Lautour's paintings often incorporate the kinds of symbols that are displayed externally as cultural or social codes – tattoos, graffiti, insignia, heraldry – and the images he has used here have meaning in a range of contexts. It is also possible, however, to regard this as an interior, rather than exterior, view – an MRI-like cross section in which the inner life of the anonymous subject is revealed as a flurry of synaptic flashes. The resulting sense of vulnerability, juxtaposed with Head's more menacing elements – the neck chain and padlock, the lightning bolts and cobweb tattoo – lend this black and blue woodcut an intriguing ambiguity. De Lautour's works often have this quality, juxtaposing vaguely threatening imagery with unexpectedly delicate detailing or lacing the picturesque with seedy, sinister undertones. In Fatal Shore (1999), another work from the Gallery's collection, he mischievously despoiled the chocolate-box landscape of an earlier artist, inserting a sinister-looking settler's cottage surrounded by oddly shaped open graves.

Profile portraits have been part of art since its earliest origins, when the first likenesses were captured by tracing a line around the shadows cast on walls. They recur regularly in de Lautour's paintings, from the snarling kiwis of his early, heavy impasto grunge-fests to the European and Māori silhouettes he lined up like entries from an ethnological textbook in the early 2000s. This is something of a de Lautour trademark – the embedding of art historical and cultural references within works that always feel effortlessly contemporary.

With so much to divert the eye and imagination, it would be easy to overlook the technical accomplishment represented when an artist renders an image like this as a woodcut. But just as the cartoonist Bob Thaves admonished Americans to remember that Ginger Rogers did everything Fred Astaire did, except backwards and in high heels, it's worth considering that the entire composition – including the subtler details, such as the shadow on the chain or the specks of blue that turn the black background into a star-filled galaxy – was conceived and executed entirely in the negative.

Tony de Lautour Head 2007. Woodcut. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, donated to the Gallery by the Kowhai Press 2007. Reproduced courtesy of the artist