B.

The sound of painting

Behind the scenes

Noise travels, and so does some painting.

One of the pleasures of installing Shane Cotton's show The Hanging Sky at Campbelltown Arts Centre in Sydney this week has been the very long views of several key paintings. And none is longer than the view of Head#!?$, a big painting completed for the exhibition in late 2012, and one of my favourites in the show.

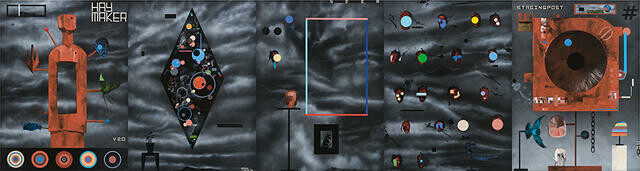

Installation view of Shane Cotton: The Hanging Sky at Campbelltown Arts Centre, Sydney.

This work is the first you see as you approach the show, way off on the end wall of Campbelltown's central exhibition hall. It's a surprisingly long walk to reach it, and, the closer you get, the more there is to discover. But it says a lot for the painting that it 'sounds' with perfect clarity from even twenty metres away.

Maybe we should call on acoustic imagery more often when describing the effects of visual art. Here the blue target form seems to sit right up on the painting's surface; it doesn't recede or open up atmospherically. So when Cotton drops modelled forms in front of it, they pop out from the flatness aggressively, like separate sounds bouncing into the room off the visual equivalent of a kick-drum.

Shane Cotton, Head#!?$, 2009-2012, acrylic on canvas. Private collection. Photograph: John Collie.

The musical comparison is useful. Throughout his career Cotton has often been treated as a kind of commentator and spokesman – an artist doing the research and laying out the issues for the edification of the art-world audience.

But I think that Cotton, in common with many artists, is less like a spokesman or researcher than he is like an experimental musician. What he wants is not to be clear or persuasive but to make a bigger and stranger noise.

And Head#!?$ really turns up the volume.