Buck Nin

Aotearoa New Zealand, b.1942, d.1996

Ngāti Raukawa,

Ngāti Toa,

Māori

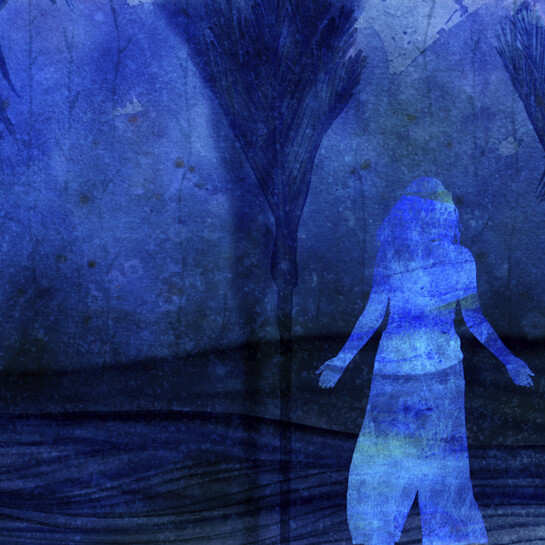

The Mamakus

- c. 1975

- Acrylic and fluorescent paint on board

- Purchased 2002

- 835 x 1065mm

- 2002/214

Location: Sir Robertson and Lady Stewart Gallery

Tags: abstraction, clouds, koru (pattern), landscapes (representations), Māori (culture or style), patterns (design elements), roads, spirals (geometric figures), urban landscapes

Buck Nin is an important Aotearoa New Zealand painter of the twentieth century. He grew up in Te Tai Tokerau Northland, with whakapapa to Guangzhou, China through his father and Horowhenua through his mother. In 1992 Nin spoke about what inspired his work: “The land is our heritage. It is the basis from which all creativity stems in Māoridom. For me it is a very strong element for its sustenance, its spiritual reality and the enlightenment it brings to my work.” In this work, Nin paints the Mamaku Ranges, which lie to the west of Lake Rotorua. Laid over the abstracted landforms are Nin’s interpretations of the carved prow and stern of Te Winika, the nearly 200-year-old waka taua. In the 1930s, Te Winika became a symbol of the Kīngitanga and the waka renaissance initiated by Te Puea Herangi.

whakapapa ~ genealogy, lineage, ancestry

waka ~ taua war canoe

Kīngitanga ~ the King Movement which developed in the 1850s to stop the loss of land to colonists, maintain law and order and promote traditional values and culturewaka canoe

He Kapuka Oneone – A Handful of Soil (from August 2024)

Exhibition History

Untitled #1050 25 November 2017 – 14 October 2018](https://christchurchartgallery.org.nz/exhibitions/untitled-1050)

“Land is essential to the Māori people because it’s been used by the ancestors for centuries. I believe that during that time, of centuries past, there has been a spiritual content left in the land. This spiritual content infuses and gives soul to the land and in turn the land gives it back to us and humanises our soul because of our ancestors.”

In this painting Nin’s inspiration is the Mamaku Range lying just West of Rotorua. Landforms have been simplified while an abstract pattern based on the traditional prow and stern carvings of the famous 200 year old Māori war canoe, Te Winika, has been overlaid.

Nin said, “I’ve taken that whole aspect of the canoe prow and the stern post and looked at it and planted it on my painting so that you look through the lattice-work, as it were, into the land, through into the soul of the land.”

Studying art at Ilam Art School here in Christchurch during the 1960s, Nin emerged as a modernist painter interested in abstraction which he combined with Māori culture. His time at Ilam “opened the door for me to bridge the gap between the Pākehā world […] and the Māori world. My paintings are a synthesis of the bi-cultural situation that we have here in New Zealand.”

—Buck Nin, 1981

Kōwhaiwhai 3 September 2016 – 6 February 2017

By the 1970s, Buck Nin was at his zenith, producing such distinctive work not seen anywhere before and yet absolutely New Zealand in its presence. Looking at this painting, we can see three horizontal elements at work: the purple and lavender skyline; the hills that speak strongly of Colin McCahon’s awesome influence upon the cultural and emotional view of the New Zealand landscape; and then, seemingly floating out from that same landscape, or perhaps beneath it, a cloud-like presence that suggests a body. We might assume this body to be Papatūānuku, earth mother, the entity that is landscape. The markings upon this figure work in complex ways. The artist said of the work, “I have taken that whole aspect of the canoe prow and sternpost and … planted it on my painting so that you look through the lattice-work … into the soul of the land.”

Untitled #1050 25 November 2017 – 14 October 2018

“Land is essential to the Māori people because it’s been used by the ancestors for centuries. I believe that during that time, of centuries past, there has been a spiritual content left in the land. This spiritual content infuses and gives soul to the land and in turn the land gives it back to us and humanises our soul because of our ancestors.”

In this painting Nin’s inspiration is the Mamaku Range lying just West of Rotorua. Landforms have been simplified while an abstract pattern based on the traditional prow and stern carvings of the famous 200 year old Māori war canoe, Te Winika, has been overlaid.

Nin said, “I’ve taken that whole aspect of the canoe prow and the stern post and looked at it and planted it on my painting so that you look through the lattice-work, as it were, into the land, through into the soul of the land.”

Studying art at Ilam Art School here in Christchurch during the 1960s, Nin emerged as a modernist painter interested in abstraction which he combined with Māori culture. His time at Ilam “opened the door for me to bridge the gap between the Pākehā world […] and the Māori world. My paintings are a synthesis of the bi-cultural situation that we have here in New Zealand.”

—Buck Nin, 1981