For the Price of a Pint of Beer

British Linocuts from the Jazz Age

Claude Flight Speed c.1922. Linocut. Collection of Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, gift of Rex Nan Kivell, 1953 (1953-0003-92) © Claude Flight. All rights reserved 2024 / Bridgeman Images

One of the joys of working at a public art gallery is the opportunity to really get to know an institution’s collection. I still remember, as a newly appointed curator of works on paper at the Robert McDougall Art Gallery, coming across a cache of the brightest, most colourful and energetic prints I had ever seen among the Rex Nan Kivell collection of modern British prints. Given to the Gallery in 1953, the sheer breadth and depth of Nan Kivell’s incredibly comprehensive gift, especially when combined with the works he gave to Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki and Dunedin Public Art Gallery, makes this a collection of British linocuts to rival those in major collections throughout the world.

This is but a brief overview of the linocuts in One O’Clock Jump: British Linocuts from the Jazz Age, which features over sixty-five works by both well-known and less familiar artists. The British linocut movement of the 1920s and 1930s has recently garnered much more international attention than when Nan Kivell made his gifts in the early 195Os, and examples have been added to prestigious art museums such as MoMA and The Met. One O’Clock Jump gives Waitaha Canterbury audiences a great opportunity to experience a wide selection of linocuts from this internationally renowned print movement.

Waitaha Canterbury-born Rex Nan Kivell came from a working-class background but, on finding himself in England after World War I, managed to climb the social ladder. A generous benefactor took him under her wing, and by the late 1920s he had become a highly respected art dealer and the director of London’s Redfern Gallery. He actively promoted artist’s prints at the Redfern, including holding Claude Flight’s groundbreaking exhibitions of British linocuts. In 1951 and 1953, Nan Kivell made a series of significant gifts totalling 1,370 linocuts, wood-engravings, lithographs and woodcuts by twentieth-century British printmakers to the four main regional art galleries in Aotearoa New Zealand. Among these gifts were more than 280 examples of linocuts from the 1920s and 1930s.

The linocut was a new form of relief printmaking that emerged in the early twentieth century. It used linoleum floor covering as the relief block that images were cut into, which made it incredibly affordable and democratic for artists and art students alike. Flight taught the medium at the Grosvenor School of Modern Art in London from 1926 to 1930 and organised the First Exhibition of British Lino-Cuts at the Redfern Gallery in July 1929. He was an inspired teacher who was popular with his pupils, and his linocut exhibitions, which continued annually until 1937, were for both artists and students. He famously espoused that the linocut should be an artform within the reach of everyone: “Linoleum-cut colour prints could be sold ... at a price which is equivalent to that paid by the average man for his daily beer or his cinema ticket.”1 He firmly believed that the simplicity of technique in the colour linocut led to simplicity of expression.2 Flight and his followers from this period were very much pioneering printmakers:

The lino-cut is different from other mediums, it has no tradition of technique behind it, so that the student can go forward without having to think what Bewick or Rembrandt did before … he can do his share in building up a new and more vital art for tomorrow.3

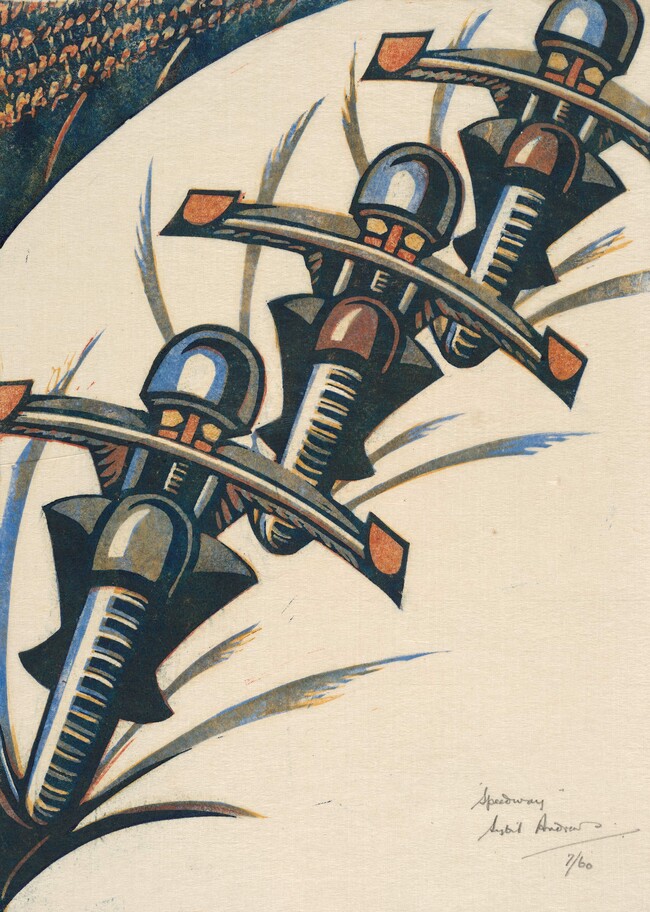

Sybil Andrews Speedway 1934. Linocut. Collection of the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, gift of Rex Nan Kivell, 1953. © Estate of Sybil Andrews, Glenbow, Calgary, Alberta

One of the most successful linocut artists of the time was Sybil Andrews. Her work in the medium was visually engaging and technically proficient, and she was prolific in her output, completing around seventy-five linocuts over her long career. One of her key prints is Speedway (1934), which focuses on the riders and souped-up motorcycles competing in the new sport then known as dirt track racing. Incredibly popular at the time, massive crowds were drawn to witness motorcycles (with no brakes!) riding around a dirt track at high speeds. In this print, the riders and motorcycles become one and the repeated patterns of the bikes and the dust being kicked up by their tyres create a unison and rhythm that was utterly modern. With its emphasis on broad, simplified forms and strong colours, the newly developed linocut was the perfect medium to capture the speed and rhythm of this modern motorsport. The scene is one of excitement and Andrews wrote of this print, “seeing the boys come sweeping round the corner in a line, looking like a lot of goblins … it’s the action I’m always looking for.”4 She puts the viewer right in the middle of the track amongst all the excitement and noise of the motorcycles. Flight could not have asked for a more perfect illustration of the linocut’s ability to convey scenes from modern mechanised life.

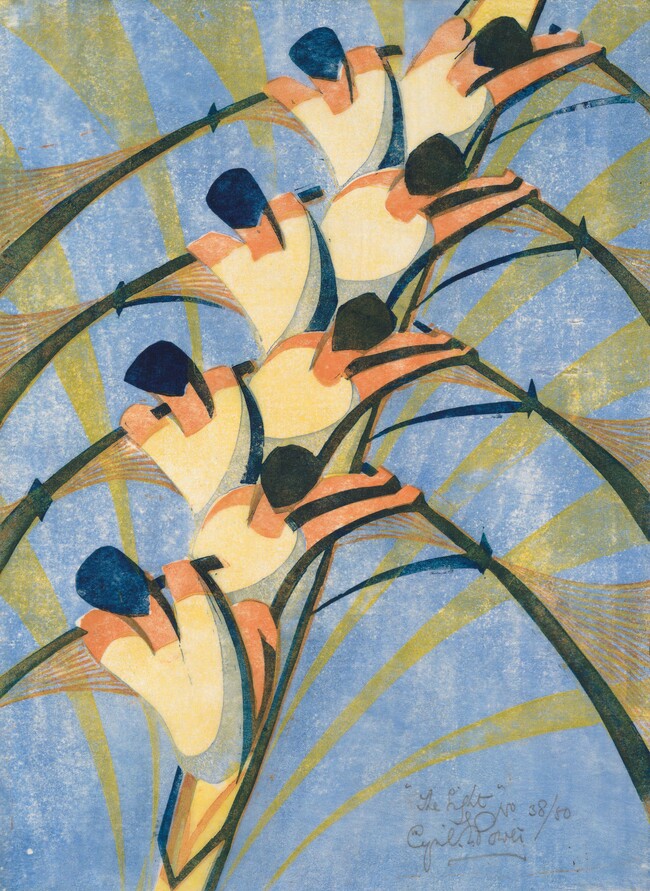

Cyril Power was a close artistic partner of Andrews, and also produced some extraordinary colour linocuts. His stunning print The Eight (1930) was observed from London’s Hammersmith Bridge, a short walk from Cyril and Sybil’s studio at Brook Green. The rowers are taking part in the Boat Race, an annual showdown between the rowing teams of Oxford and Cambridge universities. Power creates a harmonious image of the rowers in unison – arms stretched out and bodies coiled as they rhythmically pull on their oars. Tension and strength are conveyed in the bend of the oars; the unfurling yellow lines representing the energy of the participants and the wake of the boat as it cuts through the water.

Cyril Power The Eight c. 1930. Linocut. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of Rex Nan Kivell, 1953

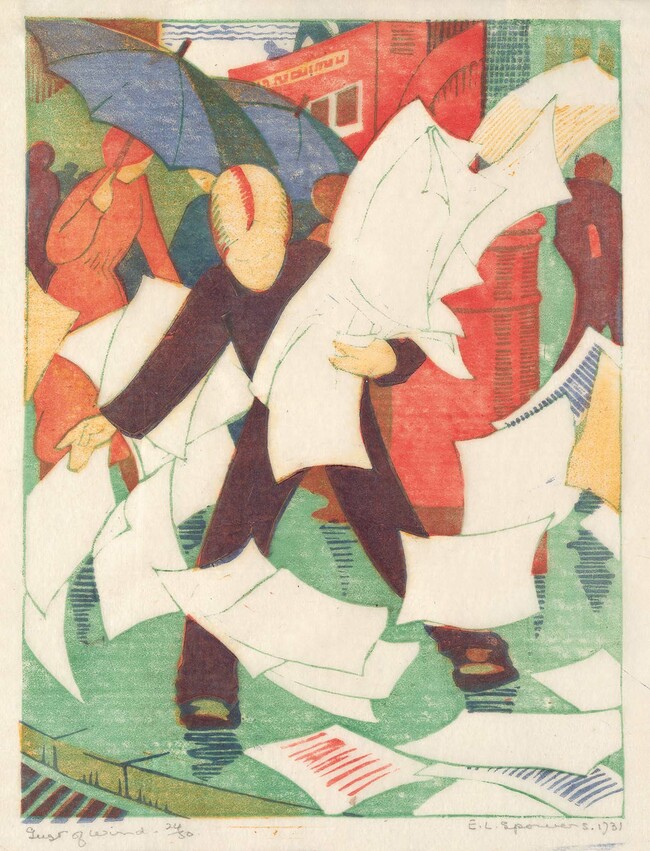

Australian artist Ethel Spowers thrived as a linocut artist at the Grosvenor School of Modern Art when she studied under Flight in 1928–9. She also became a champion of the linocut and by 1930 she was arranging exhibitions in Australia that encouraged many contemporary Australian artists to work with the medium. Gust of Wind (1931) is one of her most highly acclaimed linocuts. It captures the moment a stack of papers is blown like feathers from the arms of a figure and scattered across a wet street. As one of the most skilled and accomplished linocut artists from this period, Spowers revelled in the ability of the medium to express Flight’s theories on dynamic tension and rhythm,5 seen in the papers swirling around the central figure as they grasp to contain the maelstrom.

Ethel Spowers Gust Of Wind 1931. Linocut. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of Rex Nan Kivell, 1953

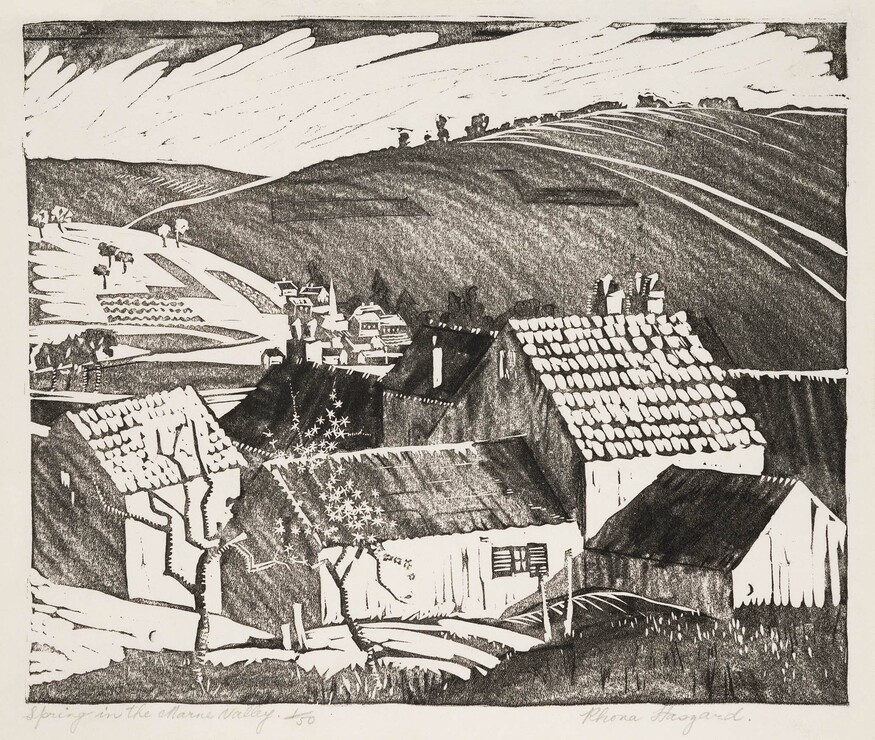

I am particularly interested in the Aotearoa connection with the British linocut movement. Rhona Haszard and her husband Leslie Greener, who had both studied in Ōtautahi at the Canterbury College School of Art in the 1920s, were in London in 1929 and became captivated by the new medium. Back at their home in Alexandria, Egypt, they began creating linocuts in earnest in 1929–30 and exhibited these together in Alexandria in May 1930. They also sent examples to Flight and these were included in the Second Exhibition of British Lino-Cuts at the Redfern Gallery in July 1930. Unfortunately, only one example of Greener’s linocuts is known to have survived, part of a gift of prints presented by Nan Kivell to the Aberdeen Art Gallery in Scotland in 1951. It would appear that the remainder of his linocuts, which he exhibited here in Ōtautahi with The Group in 1933 and 1936, were lost when his house was destroyed in Tasmania’s devastating Black Tuesday bushfires of 1967. There are however a handful of surviving linocuts by Haszard held in Aotearoa collections. One, Spring in the Marne Valley, was included in the Second Exhibition of British Lino-Cuts. It is an excellent example of Haszard’s refined shading technique, in which she burnished the back of the printed paper with a printmaker’s baren to transfer ink using just a single linocut block.

Rhona Haszard Spring in the Marne Valley c. 1930. Linocut. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, gift of the Auckland Society of Arts, 1933

Another Aotearoa artist of note is Frank Weitzel, who grew up in Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington and studied overseas in San Francisco and Munich. In 1928 he moved to Sydney and became part of the city’s burgeoning modern art scene. His close associations with Australian printmakers Thea Proctor and Dorrit Black led to his interest in the linocut. Weitzel relocated to London in 1930 and was invited by Flight, who had earlier taught linocut to Black, to contribute work to his Second Exhibition of British Lino-Cuts. His linocuts were included alongside examples by Haszard and Greener. In a letter to Black, Flight wrote that he was “very pleased to have Mr Weitzel’s work for the show. I like it very much, it’s original, strong, good of its kind & just the sort of work we want.”6 Haszard and Weitzel had incredibly bright futures as artists ahead of them, but both died tragically young in 1931 and 1932 respectively.

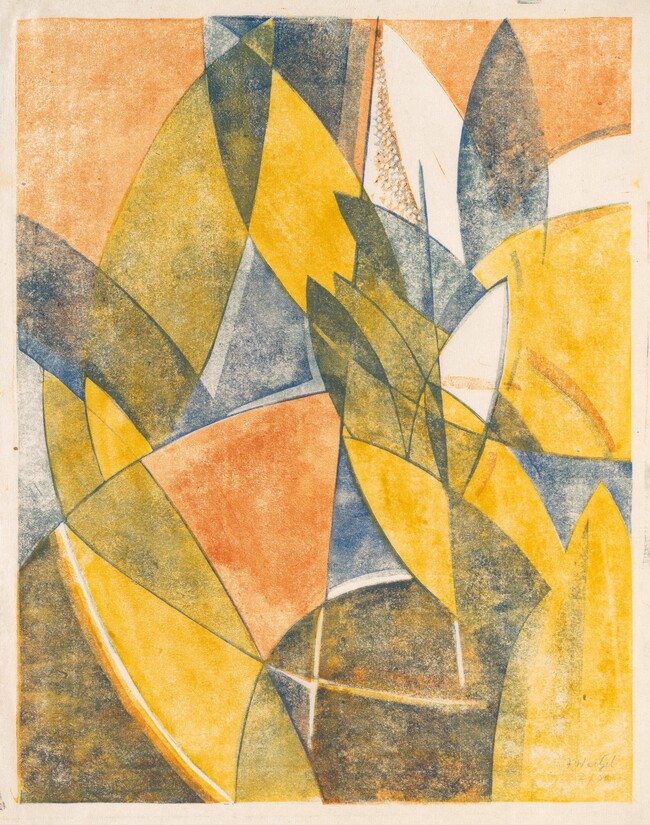

Frank Weitzel Abstract Design 1931. Linocut. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of Rex Nan Kivell, 1953