Marilynn Webb

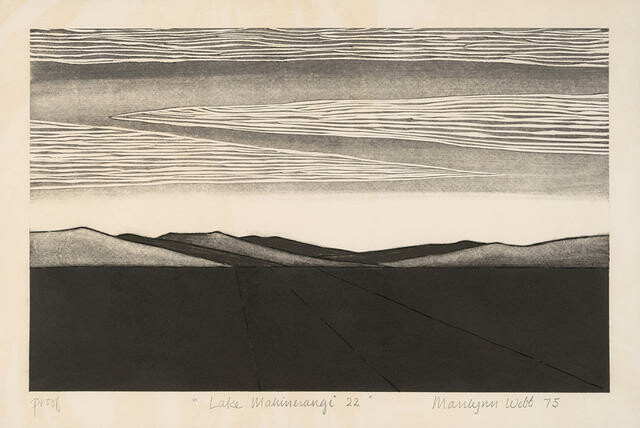

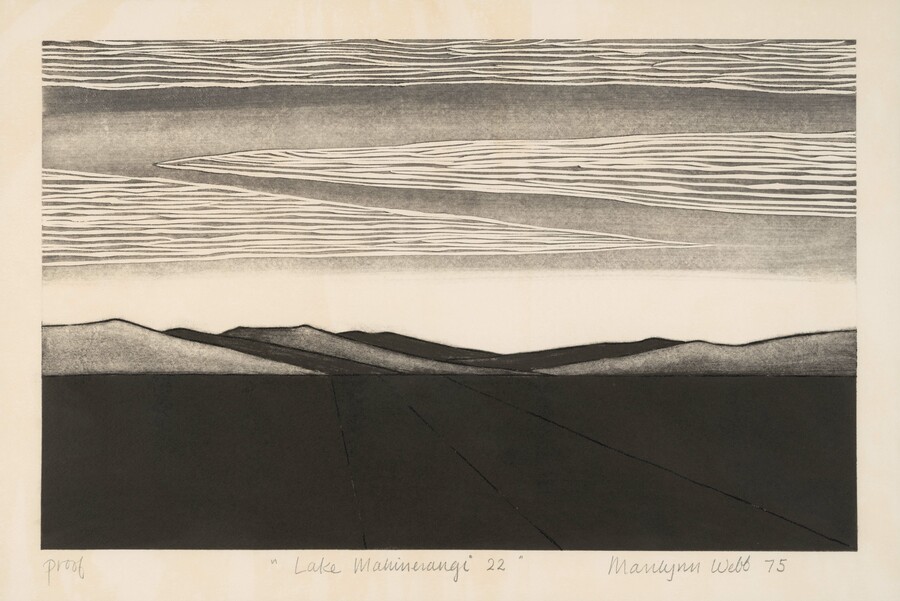

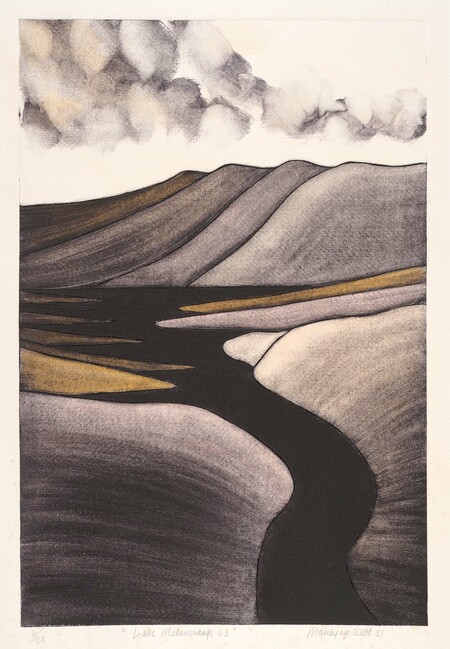

Marilynn Webb Lake Mahinerangi 22 1975. Etching. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu, gift of Holcim (New Zealand) Limited, 2003

He mana ā whenua, he mana wahine

Female power comes from the earth

As I write these pages, I remember the stories Marilynn Webb told me.

In Te Tai Tokerau – Northland, early 1960s – Marilynn met with her colleagues Ralph Hotere and Muru Walters to plan their arts teaching programme. As promising graduates of the innovative Art and Craft Scheme to foster Māori education, they were based in their home territory. Although raised in Ōpōtiki, Marilynn’s Māori genealogy connected her to Ngāpuhi, Te Roroa and Ngāti Kahu. Like the men, she was home. When they asked her, “Can you cook?”, she promptly snapped back, “Of course I can!”

That encounter she’d often recall with some relish; the question summarised all the challenges and expectations that she experienced over the ensuing decades. She flowed with them, and around them; she chose when to speak, and when to remain silent, and the eloquence of her work sharply defined her response. To those men, to the world, and to us.

I was invited to write about why Marilynn matters, and what she was for us, what she meant. To describe in readable, easy language, for the general public, how I feel about her legacy and her work, as an artist, as a Māori, as a woman, as an educator.

Taku mareikura, tangi tonu te ngākau mōu. Tears are still fresh on our faces; what do I say about you?

![Photographer unknown [Marilynn Webb] c. 1975. Uncatalogued archival material. Marilynn Webb Estate collection, Hocken Collections Uare Taoka a Hakena, University of Otago](/media/cache/2b/78/2b7820ff140e3844f72eb6be755d5a48.jpg)

Photographer unknown [Marilynn Webb] c. 1975. Uncatalogued archival material. Marilynn Webb Estate collection, Hocken Collections Uare Taoka a Hakena, University of Otago

After teaching for a few years, then taking off to enjoy crafts and creative adventures around the world, Marilynn returned to Aotearoa, and the Frances Hodgkins Fellowship in Ōtepoti Dunedin. And thus the far south, its landscape, people, vegetation, energies and differences, became the place of her soul. She had an entire year, financially supported and housed with a studio, to do nothing but make art. Nothing else! This enthralled her. After fifteen years of managing her teaching commitments and squeezing her creative endeavours around that full-time job, she experienced the freedom and the pure joy of focusing on her passion. Doing her real work. She produced, she crafted, she experimented, she played. Her friendship with Ralph Hotere deepened and, with Hone Tuwhare staying around after the Burns Fellowship, the fires of Te Tai Tokerau smouldered and cast their special glow across the far south. As artists, they were all politically aware and active, supporting Māori rights, and damning the Apartheid regime, the Vietnam war and nuclear testing, especially in the Pacific. These salient issues inspired many important works from all of them. Sometimes they’d collaborate, and the spell-making of Tuwhare enhanced the images of Hotere and Webb – all voices from the far north, from another island.

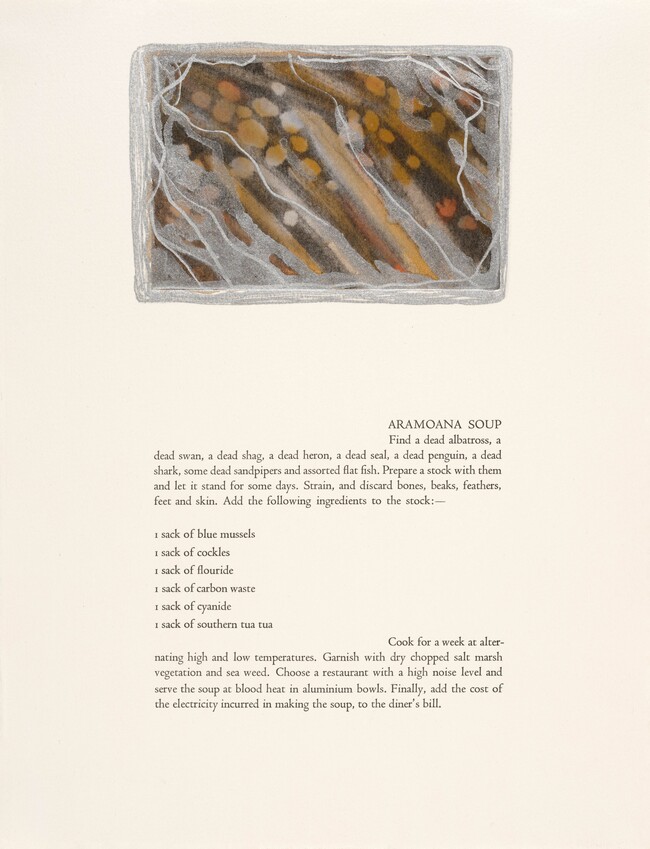

The 1974 campaign against the proposed aluminium smelter at Aramoana ignited her genius for subtle protest and she created exquisite works. She mastered and manipulated different techniques and technologies, some requiring immense physical strength; and she resumed teaching and mentoring in the tertiary sector. She considered printmaking to be a woman’s art form; neglected as mere craft, yet responsive to time, action, space. And so transportable; she observed that works could be rolled up carefully in a tube and just posted off, rather like an ordinary parcel, anywhere around the planet. It was accessible, affordable and gratifying too. She reached so many people and places; her elegant little Christmas and New Year cards – small prints on her favourite themes – remain a treasured wonder in many homes around the country and the world.

Marilynn Webb Aramoana Soup 1982. Monotype. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu, purchased 1983

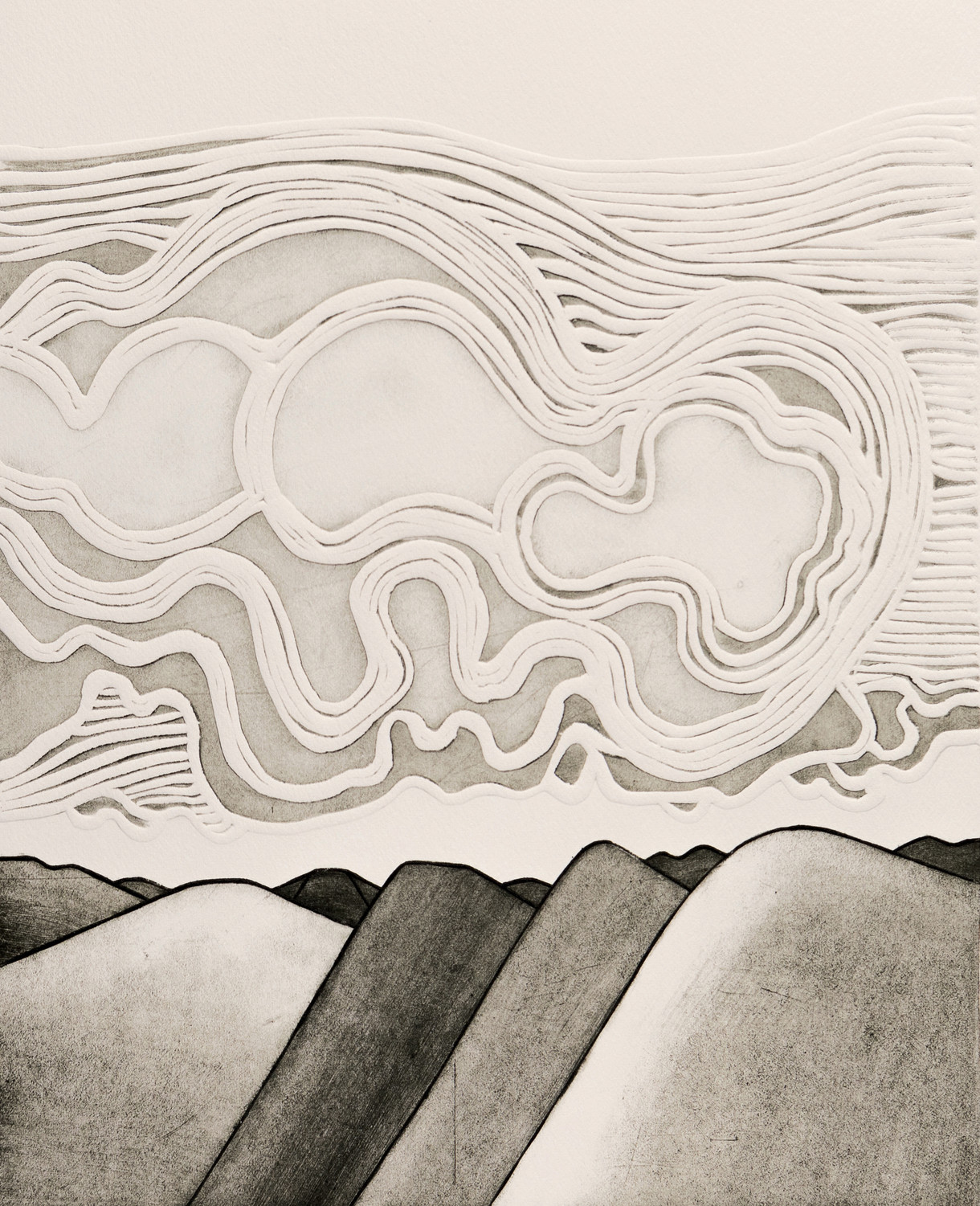

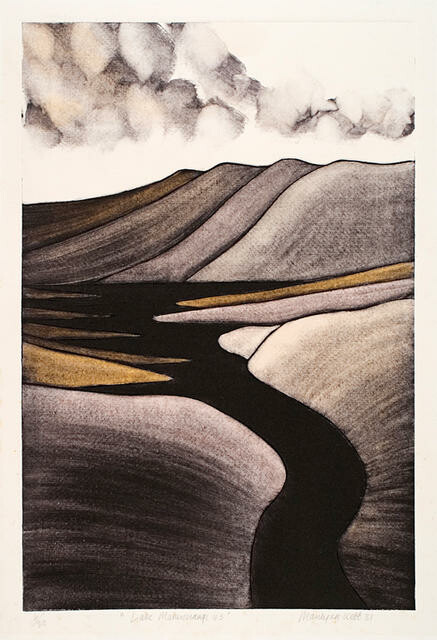

Marilynn Webb Lake Mahinerangi 43 1981. Etching. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu, Lawrence Baigent / Robert Erwin bequest, 2003

Marilynn maintained a high level of studio practice, even during the enriching diversion of motherhood with young Ben, and she consistently produced works of calibre, provocation and beauty. She explored and experimented; she was excited by the new. Some projects, like the commissioned exhibit Taste Before Eating for the Dowse Art Museum in Lower Hutt, revealed a quirky sense of humour, reducing significant sites to edible and extreme foodstuffs, consumables. Literally cooked up and served, they were the boiling down and reduction of potential crisis and calamity.

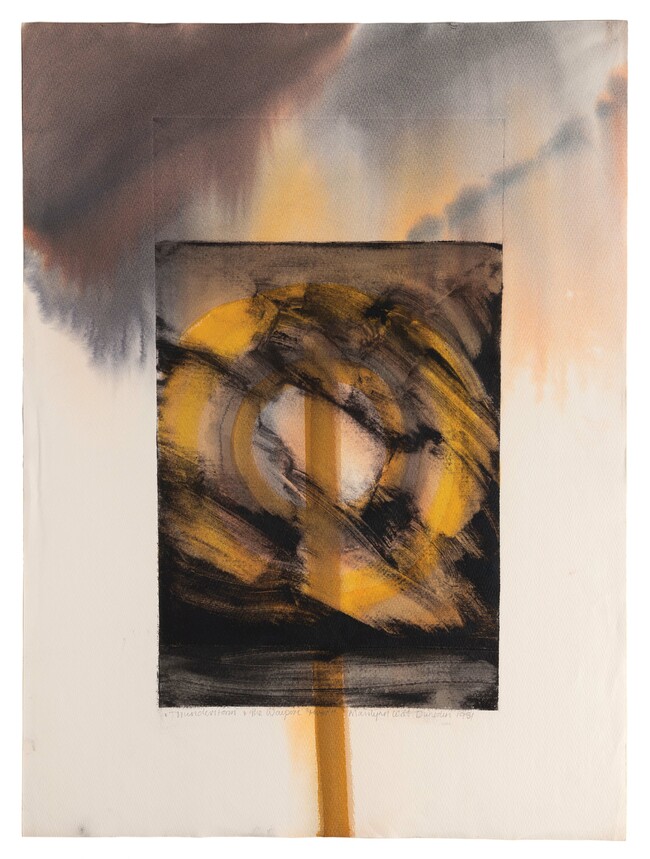

Throughout the decades, Marilynn considered the threat of environmental catastrophe, envisioning the possibility of a nuclear Pacific, emphasising her strong faith in the relationship between tangata – the people – and whenua – the land. Or moana, the ocean. However profound and possible the looming threat, there is still a sense, a line, a thread of hope, of light, that comes through, lifting the heart of the viewer, honouring the mana of Papatūānuku, the Earth Mother Gaia; promising to sustain and protect her. Marilynn’s work was deeply personal, and this exposure required courage. Hers was a profound sense of purpose, showing and sharing her inner self and her own experiences through the placement of her hands upon the surface of her works, asserting her continuous presence within each image. Hands demonstrate and deliver mana – they are instruments of creativity, action and commitment. With her hands, Marilynn spoke truth to power. She produced imagery that either predicted or documented change. Nuclear testing, the toxic aluminium smelter, the irreplaceable loss of natural habitat and endemic vegetation – she persisted in making images of protection, of active defence, to counter spiritual and physical incursion, and she achieved this by maintaining a consistent and fierce work ethic until her last days with us. From the teaching workshops to her glorious Dowling Street studio, then on to her lush, layered garden and spacious, light-filled villa in Mornington, there was always something in progress. She taught not by telling, but by showing – her hands-on, fingers stained, aching- arms-and-shoulders-and-lower-back approach mentored an outstanding flow of students, most of whom remain in the sector as practitioners, teachers, writers and curators; they are a vital part of her legacy. Some contributed to the magnificent survey exhibit, Folded in the Hills, a visual triumph that resonates from 1968 to her final years and is a revelation of her many ways of seeing. Of reminding us. For me, Marilynn matters because hers was a life of giving, of understanding the human spirit, of growing. She decided to live and flourish far away from the earth of her own bones and blood; she constructed a lifeway as her ancestors did, after crossing oceans and continents. She gazed into the still, smothering waters of Mahinerangi, and inhaled the stained and streaked horizons of Māniatoto, and she remained with them, and they embraced her. She made her choice.

Marilynn Webb Thunderstorm and the Waipori River 1981. Hand-coloured linocut on paper. Marilynn Webb Estate collection

Takoto mai rā koe, e tai, i te poho o Papatūānuku; kia tupu anō tō pākārito.

Rest well in the breast of the Earth Mother, for your legacy will flourish.