Down and Gritty

The art history of Aotearoa New Zealand includes a subgenre of landscape painting that is often under recognised, but enlivens the story of this country in gritty, illuminating ways. Investigating the twentieth-century painters who focused on the urban and industrial exposes a rich seam of material, with subject-matter ranging from gasworks, hydroelectric plants and foundries to factories, warehouses and cityscapes, workshops, wharves and railway yards. The artists are a combination of well known and less familiar names, but it is notable that this direction developed most strongly among the Ōtautahi Christchurch-trained: two-thirds of the artists in From Here on the Ground attended the Canterbury College School of Art, where many also taught. It was a training ground regarded as among the most progressive in the Southern Hemisphere for several decades in the first half of the century.

Rhona Haszard Untitled (Looking Through Strand Lane from Hereford Street, Christchurch) 1921. Oil on canvas board. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2002

Housed in a Gothic Revival-style building by the Botanic Gardens on the corner of Hereford Street and Rolleston Avenue, the school’s location encouraged the pragmatic use of its natural and built surroundings. Students were directed to paint and draw on the Ōtākaro Avon riverbank or to survey architectural spaces such as the nearby Provincial Council Chambers, sketching in its corridors or from selected roof positions. A striking example of a student response to the city’s built fabric appears in a work in oils by Rhona Haszard from 1921, framing an outlook a little further up Hereford Street. The view is through Strand Lane to Cathedral Square, where lined up motorcars sound a stylish, modern note.1

Much of the city’s art teaching and exhibiting activity occurred in proximity to the college, and many of the tutors lived or had studios nearby. The main local exhibition venue, the Canterbury Society of Arts, was a zigzag across the grid to the corner of Durham and Armagh streets, where the latest productions were presented annually in end-of-summer shows. In 1927, a small clique of mainly local graduates, announcing themselves as The Group, held their first exhibition in a shared upstairs studio space in Cashel Street, making a demarcation towards a more modern approach.

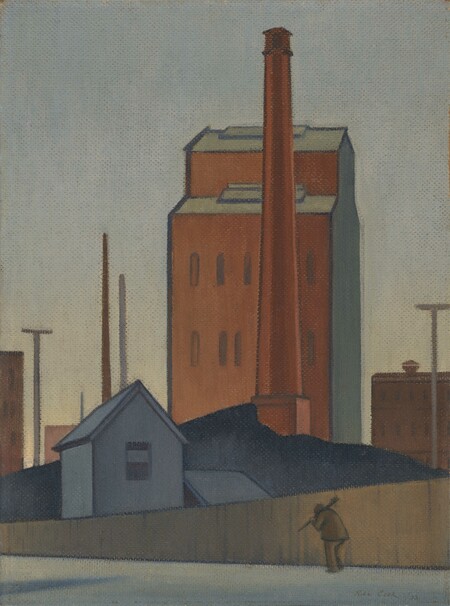

Rita Angus Gasworks 1933. Oil on board. Private collection. In memory of Beryl Jones

A newly arrived student at the School of Art that year was Rita Angus, who would later exhibit with both groups and extend the urban and industrial genre. At the beginning of 1933, the height of the Great Depression, Angus was living at 120 Ferry Road, an unlikely cultural hub on the edge of industrial Waltham, under the same roof as her husband Alfred Cook as well as his mother and brother James, a teacher at the Canterbury College School of Art. Rita’s youngest sister Jean had also just joined the household, arriving from Napier to study at the school. Angus’s marriage was becoming more than strained, and the couple would separate in the following year. From this constricted domestic setting, Angus took a short walk to make sketches at the nearby Christchurch Gas Company, marshalling resources to paint her memorable Gasworks, a small painting with psychological resonance. Featuring a lone figure, burdened and sympathetically portrayed, walking beneath an unyielding industrial framework, it also reflects something of the societal pressure of this time. Angus extracted material for two paintings from this atmospheric location, showing these alongside four other new works at the Canterbury Society of Arts in 1933. Gasworks, offered at five guineas, was the work that made ripples.2 A Coal Yard, at four guineas, was not mentioned in reviews and remains unlocated. Angus found friendship and solidarity with other artists including Louise Henderson, a Paris-born embroidery and interior designer who settled in Christchurch in 1925, began teaching at the School of Art and became similarly drawn to industrial subject-matter. In the spring of 1933, Henderson exhibited seven works at the inaugural New Zealand Society of Artists exhibition in Christchurch, including four titled Halswell Quarries, Industry, Brick Works, and Brick Kiln, Opawa – all now unknown and with an obviously non-scenic, gritty focus. Prior to the exhibition, Henderson had shown only textiles locally; her ability with colour and com- positional structure now came to the fore in a different way. Her transition to paint also impressed a reviewer who noted

“Mrs L. Henderson, known as a craft worker, surprises by the ability of her oil paintings.”3

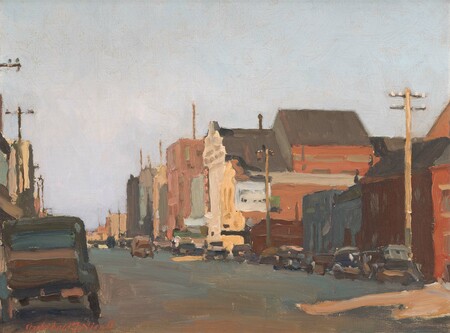

Louise Henderson Manchester Street, Christchurch c. 1933. Oil on board. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, Dame Louise Henderson Collection, presented by the McKegg Family, 1999

Archibald Nicoll Industrial Area 1941. Oil on canvas board. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2004

Another of Henderson’s works in the 1933 catalogue was View from Studio Window, which it is tempting to correlate with her attentive architectural interpretation of a section of Manchester Street, east of Cathedral Square. Scanning Post Office directories from the period doesn’t line her up neatly with a studio in the place we know it was painted – the seven-storey New Zealand Express Company Building (more recently known as Manchester Courts, a survivor until the earthquakes). But it feels like an outlook she knew well before she chose to paint it.

Many of the locations pictured in works in this show carry close personal associations for the artists who made them. Among these is Archibald Nicoll’s Industrial Area. Nicoll found good, paintable material not far from his rented studio on Cambridge Terrace, in the lines of warehouses, factories and cars on Tuam Street. Director at the School of Art through the 1920s and later solely a teacher, Nicoll became regarded a leader in what became known as the Canterbury School. The art school’s curriculum habitually included sending students off on bicycles to sketch and paint at visually complex locations such as the several brick- works along Port Hills Road in Hillsborough and St Martins. With its bicycle propped against a lamppost, evidence of a nearer-to-town cycle mission comes in Juliet Peter’s Poorer Christchurch, painted in about 1938 while still a student. The title shows she has ventured beyond her usual home territory: the towering chimney behind the old wooden houses suggests this could be Rita Angus’s old neighbourhood.

Juliet Peter Poorer Christchurch c. 1938. Watercolour. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of Alastair and Gaelyn (Ensor) Elliott, 2018

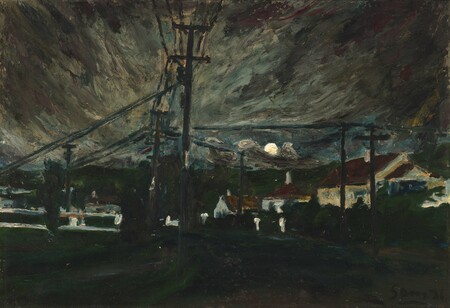

Sam Cairncross Moon Over McKillop Street, Porirua 1974. Oil on board. Collection of Rognvald and Deborah Harcus

Juliet Peter was among the many to be impacted by the onset of war in 1939. By then a Diploma of Fine Arts graduate, she took on new skills as a nursing voluntary aid and in an office at Christchurch Hospital, before joining the Women’s Land Service in 1942, established to replace younger male farm workers fighting overseas. Artists whose lives and careers were interrupted or shifted off course included more than a few who headed overseas with the armed forces. Among those set to war work on home soil was Bill Sutton, another recent art school graduate and part-time teacher, redirected into roadmaking, painting army murals and designing for the Camouflage Unit.

Artist’s families also joined this bigger picture. Louise Henderson faced imaginable disruption due to her husband Hubert’s nine-month war service as second-in-command of a trainee battalion in Burnham, before being deployed to the Western Desert. With his release from service and appointment as a secondary schools’ inspector in Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington in 1941, Henderson ended her fifteen years’ teaching at the Canterbury College School of Art to enter full-time teaching at the Education Department’s Correspondence Schools Branch, while developing its needlework and embroidery syllabus.4 Maintaining her sharp agility in this role while continuing to paint, she is one of over half the artists in From Here on the Ground who were teachers, many of these at Canterbury College. Henderson was also the first of the local leading lights in the period to head to Wellington, with the later departures of Juliet Peter, Evelyn Page and Rita Angus further depleting the local painting and exhibiting scene.

Wellington-based Sam Cairncross took a less collegial route than that available to Christchurch artists, taking his first part-time art classes at Wellington Technical College in his late twenties in 1939. Exempted from war service, Cairncross developed as a painter while working as a labourer and then as a hospital porter until 1947, when (following a solo exhibition) a French Government scholarship awarded him a year’s study in France. When he painted his semi- autobiographical Wellington Hospital in 1951, he was earning his living through painting alone.5 By 1955, Cairncross and his family were living in a modest state house in McKillop Street, Porirua. While the bustling streets and buildings of central Wellington were his favoured painting territory, he remained alert to his everyday surroundings and created something of a rarity in Moon Over McKillop Street, Porirua (1974) for its moonlit, urban working-class setting.

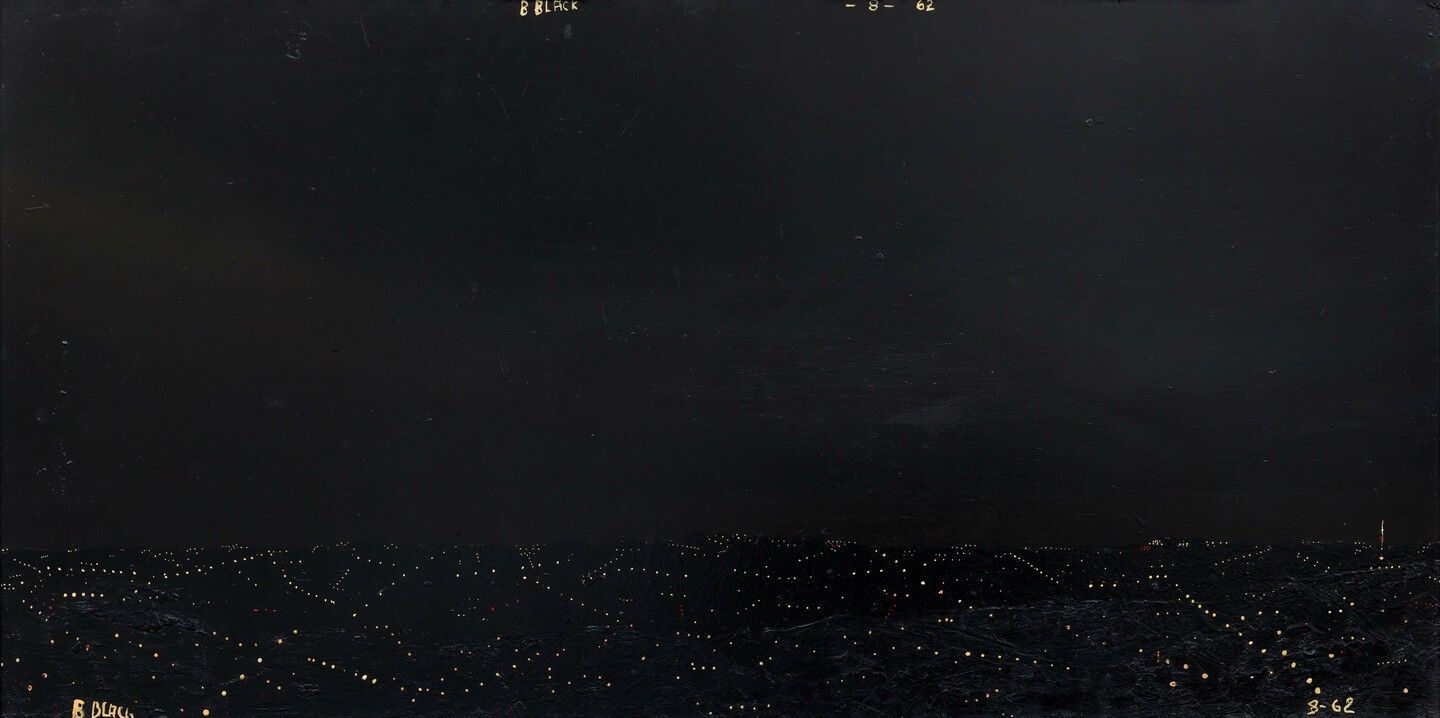

Buster Black Black Painting: Night Landscape 1962. Oil, enamel on hardboard. Collection of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki, gift of Matthew McCahon, 2008

Another Te Ika-a-Māui North Island artist in this story is Thomas Desmond Pihama (Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Rangi), better known as Buster Black, who almost exclusively employed nighttime settings.6 Born in Taumarunui in the King Country in 1932, he is understood to have destroyed most of his own work by the late 1980s, a fact made more painful through the strength of what remains. Black took up painting after moving to Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland in his mid-twenties, working as a factory hand and storeman and from 1956 attending classes at Auckland City Art Gallery, where he befriended its then keeper and newly appointed deputy director, painter Colin McCahon. Marja Bloem and Martin Browne have noted that “the two men became close friends and spiritual confidants, pupil and teacher influencing each other”, and that their “conversations … ranged across Christianity, music and painting”.7 Black’s extraordinary night scenes include distant urban vistas, punctuated as if by pinpoints of light, blinking street layouts mapping across whenua that breathes and undulates. His relationship to location here is as tangata whenua through whakapapa, and implicitly through experience of both belonging and exclusion, a double role of insider looking out and outsider looking in.

Artists appear to be most commonly drawn to urban or industrial subject-matter through personal connection, related to their own place and circumstances. There is at times a sense of calm, distanced regard, as well as regular evidence of the art school training process, with attention given to qualities of light, colour and formal or spatial relationships. This is distinct from practical recording. In a general sense, such works share a kind of exploratory conviction, a need to bring forth something truthful from where they had landed. They are about more than wanting to stand out on art society exhibition walls, and the dialogue between artists opened new possibilities for subject-matter. There are also sparks that fly between works. The paintings brought together here bring some of this into sharp detail.