Flitting, Gliding, Strutting, Cavorting

An Album of Indian Birds

Elizabeth D’Oyly and Charles D’Oyly Pin-tailed Ducks (detail) 1826. Watercolour on paper. Private collection

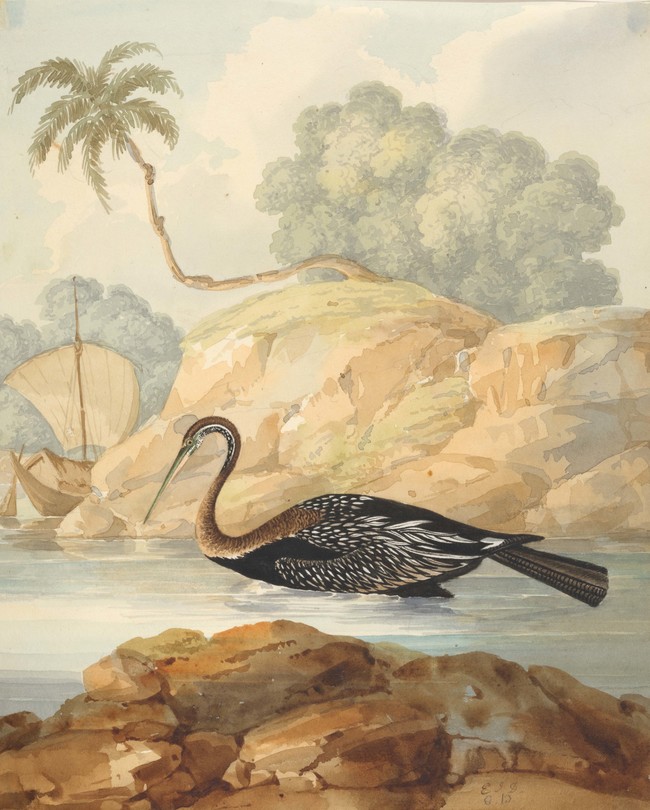

Ranking highly among the privately-owned works of art that have fallen across this curator’s path is an exquisite late-Georgian era album of Indian bird watercolours. This significant, previously unpublished folio contains twenty-five delicate watercolours and three small lithographs. Most paintings were produced collaboratively in 1826 by an interesting couple, Elizabeth (Eliza) Jane D’Oyly and her husband Charles Walter D’Oyly, the latter recognised in India as “perhaps the most famous of the amateur British artists who depicted the Indian scene.”1 A treasured gift from Elizabeth to her sister Isabella Gilbert in 1866, the album has stayed in the same family since then. It also carries sombre themes alongside its splendours.

Twenty paintings are signed by both Elizabeth and Charles, recording a productive partnership through the spring of 1826; the dates show an average of one completed every five and a half days over a four-month period. Three further works are signed only by Elizabeth, including Great Rock Eagle Owl, the last dated and one of the finest in the collection, completed 21 April 1827. Two small undated paintings are by Charles and two hand-coloured lithographs are by Elizabeth’s cousin, civil servant Christopher Webb Smith, an amateur ornithologist and undoubted influence.2 For the co-signed watercolours, Elizabeth is credited for birds, flowers and foliage, and Charles for the backgrounds.

When the album was made Elizabeth and Charles D’Oyly were living in an expansive stone bungalow in residential Bankipur – a thriving East India Company (EIC) commercial centre by the Ganges near the predominantly Hindu city of Patna in Bihar. The D’Oylys were stationed there due to Charles’s employment with the EIC, which he entered in his teens. Their move north from Calcutta (Kolkata) in 1820 came through his appointment as opium agent and commercial resident in Patna, a role in which he was expected to expand British revenue through the lucrative, and mercenarily destructive, narcotics trade.

Charles D’Oyly was prolific as a painter and lithographer and has been well recognised for his work. Elizabeth, however, has been little known as an artist and is recognised primarily as a significant early transcriber of Gaelic music. Although several of her lithographs are in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Yale Center for British Art in Connecticut and the British Museum in London, few beyond her family have seen her paintings.

Elizabeth was born in 1789 at Gowrie Castle Artillery Barracks in Perth, Scotland, the daughter of Major Thomas Ross of the Royal Artillery, who had served in the Caribbean. Her mother Isabella Ross (née MacLeod), born on Raasay in the Inner Hebrides, was celebrated for befriending Robert Burns and inspiring him to complimentary verse.3 Major Ross served next in India, where he was badly wounded in the 1792 British attack on Seringapatam. He died two years later in Madras (Chennai), aged 54. Elizabeth’s sister Isabella Rose was born in Madras three months later, and the following year their 23-year-old mother left for Scotland with her daughters on an East India Company Indiaman well-stocked with soldiers and cannons. She tragically died during the voyage in late August and was buried at sea between St Helena and England.

Elizabeth D’Oyly Great Rock Eagle Owl 1827. Watercolour on paper. Private collection

The sisters went into the care of their uncle James MacLeod, Laird of Raasay, and his wife Flora. Elizabeth studied at Mary Erskine School in Edinburgh, where she boarded with an aunt and gained a solid musical education, including on the pianoforte and concert harp. Her musical accomplishment expanded on returning to Raasay, where her uncle played violin and his clansmen were all pipers. Elizabeth transcribed several piobaireachd (Highland bagpipe compositions) into pianoforte notation and collected many local songs. By 1812, aged about 23, she had transcribed 150 “Original Highland Airs” shared by the isle’s singers and musicians, including the Laird’s principal piper.4 She remains honoured as “a poet and bard [with] a great love of the Gaelic language” and her work is celebrated.5

Elizabeth and Isabella returned to India in 1813 as wards of Sir Francis Rawdon-Hastings, who was married to their cousin Flora Elizabeth Rawdon-Hastings, Countess of Loudoun. Lord Hastings (also Baron Rawdon and Earl of Moira) had been a prominent politician as well as celebrated soldier in the American and French wars, and was India’s newly appointed Governor-General – his decade-long Indian tenure would be remembered for its aggressive military policies. Elizabeth Ross and Charles D’Oyly likely met in Calcutta at Government House. Charles was then collector of Dacca (Dhaka), a revenue administrator, as well as honorary aide-de-camp to Hastings during sessions in the capital.

Elizabeth D’Oyly and Charles D’Oyly White or Barn Door Owl 1826. Watercolour on paper. Private collection

Charles had been born in 1781 into a titled, extremely wealthy British military family in Murshidabad; his father Sir John D’Oyly was then resident at the court of the Nawab of Bengal.6 The family relocated to England in 1785 for Charles’s mother’s health. His father entered British politics and Charles received an education before himself entering the civil service, sailing to India in his sixteenth year.

In 1798, at seventeen, he was appointed assistant to the registrar of the Court of Appeal at Calcutta; at 22 he became keeper of the records for the governor- general Lord Wellesley. Charles married his first wife (and cousin) Marian Greer in 1805. Two years later he met George Chinnery, then the leading British artist in India, and when stationed to Dacca in 1808 invited him along; Chinnery lived there for three years and provided vital lessons, including on sketching tours. D’Oyly’s earliest published drawings were engravings produced in London in 1813 for The Costume and Customs of Modern India and The European in India, followed in 1814 by Antiquities of Dacca.7

Elizabeth met Charles’s first wife Marian before her untimely death in January 1814. It is said that “when dying, she [Marian] pointed out the present Lady D’Oyly as the person most likely to make him happy, and after a short time he married the beautiful Miss Ross.”8 Next to this bestowal, Elizabeth had esteemed family connections and was “was beautiful, a good musician and also a dedicated sketcher.”9 Charles D’Oyly and Elizabeth Ross married on 8 April 1816 in Cawnpore (Kanpur), he at 34, she at 26. In 1818 Charles inherited his father’s baronetcy and became collector of government customs and town duties at Calcutta. Two years later he became the East India Company’s opium agent and commercial resident (or tax collector) in Patna. He sketched and painted throughout the three-month voyage up the Ganges on a pinnace budgerow barge to create a spectacular sequence of passing ruins, towns, temples, jungles and mosques.

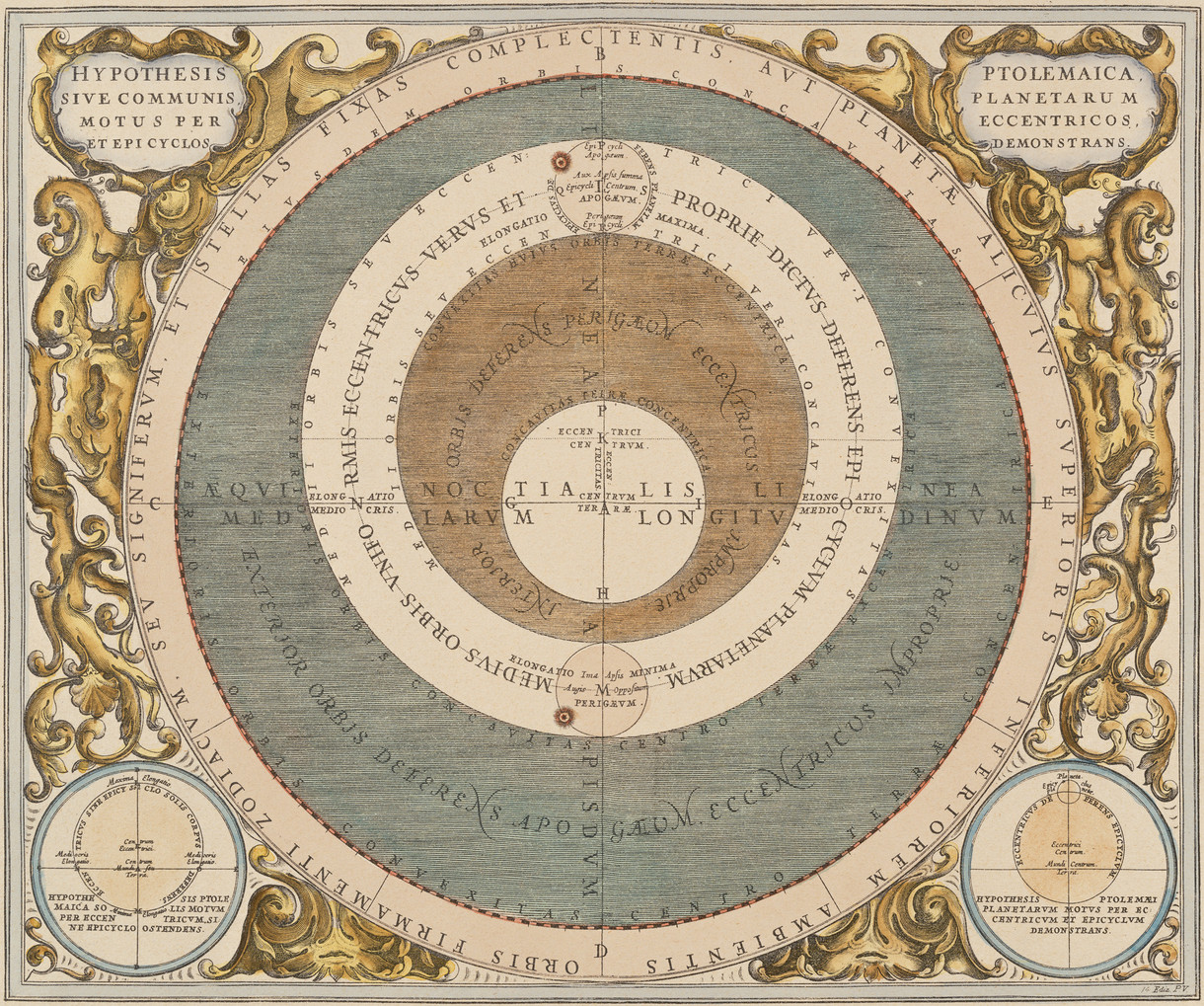

Elizabeth D’Oyly and Charles D’Oyly Large Black and White Diver 1826. Watercolour on paper. Private collection

It has been observed that “With the move to Patna in 1820, D’Oyly entered a new phase of his artistic life. His official work as opium agent seems to have left him ample time for his painting and printing enthusiasms.”10 D’Oyly’s Company role has been typically underplayed, but with opium being one of the EIC’s most profitable commodities and Patna the main centre in northeast India for its collection and manufacture, he was clearly overseeing a huge operation. The vast patchwork under poppy cultivation in the region at this time is recorded as about 90,000 acres (36,400 hectares).11

The Company maintained a strict monopoly over production and export, processing opium into cakes in its Bihar factories and warehouses before sending it downriver to Calcutta for shipping to China. The impact on Indian communities and public health included disrupted agriculture, exploitation of local farmers and reduced food security; in China it caused increasing societal damage including widespread addiction and social degradation. However, Britain evaded China’s attempts at prohibition, opium being too profitable and expedient a means of obtaining required Chinese goods, primarily tea and porcelain. Apart from silver, China spurned European commodities, and so Britain continued the opium trade with determined indifference.

The D’Oylys’ home became a cultural and artistic hub, hosting regular visitors, concerts and parties. Charles remained a prolific artist; as a contemporary observed, “his pencil like his hookah-snake was always in his hand.”12 A pair of 1824 watercolours, in the collection of the Yale Center for British Art make this visible, alongside Elizabeth playing the harp. In 1824 the D’Oylys initiated “The United Patna and Gaya Society, or Behar School of Athens, for the promotion of Arts and Sciences and for the circulation of fun and merriment of all descriptions.”13 Under this directive, “cheerful groups set off on horseback or in carriages on sketching expeditions.”14 Doubtless onboard was Elizabeth’s cousin, civil servant and amateur ornithologist Christopher Webb Smith, who married at the D’Oyly’s home in August 1824 and hosted them both in Patna later that year.15

While Elizabeth’s painting is scarcely known, she has been recorded as “a considerable artist in her own right”. Inventories dated 1830 and 1850 also record eight paintings by “Sir Charles and Lady D’Oyly”, now identified as a group of impressive oil paintings from Bihar dated around 1825.16 The collaborative 1826–27 watercolours present a world of sometimes precariously perched birds on branches, tree-trunks and craggy ledges; extracting nectar; strutting, preening, cavorting; frozen in flight; gliding afloat. All are likely based on shot specimens: one painted backdrop includes a gentleman – perhaps Smith on one of his early morning hunting walks – blasting his shotgun from a distant riverbank, behind a group of pin-tailed ducks (Anas acuta) in flight.17 Other settings include elephants, sailing vessels and people labouring in fields.

Elizabeth D’Oyly and Charles D’Oyly The Amadavad 1826. Watercolour on paper. Private collection

In 1828, Charles had a book of satirical engravings anonymously published in London, Tom Raw, the Griffin: a burlesque poem… descriptive of the adventures of a cadet in the East India Company’s service. He also launched his Behar Lithographic Press in Patna in that year.

Several of Elizabeth’s birds were thus reworked as lithographs in two self-published ornithological folios, The Feathered Game of Hindostan (1828) and Oriental Ornithology (1829), produced by Charles and Smith. Smith, however, was solely credited for the birds and Charles for the backgrounds. The Behar Lithographic Press ran with the help of Indian assistants including the artist Jairam Das. Further publications included Indian Sports (1829), Costumes of India (1830) and Sketches of the New Road in a Journey from Calcutta to Gyah (1830).

In 1832 The D’Oylys took a year’s leave at the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa, where Charles continued his art. From 1833 to 1838 they were again in Calcutta, Charles as senior member of the board of customs, salt and opium, and of the marine board, holding this post until his retirement due to ill-health in 1838. Relocating firstly to London, by late 1840 they were settled at the villa Casino Pecori overlooking the Arno in Florence, Italy. Charles was knighted in November 1843 for his work in Bengal as a civil servant and contributions to the field of art, and died in Tuscany in 1845 at Ardenza, near Livorno. Lady D’Oyly, as she now was, returned to England, settling at Iwerne Minster in Dorset. She took up composing Gaelic songs in her later years and died in 1875.

Elizabeth and Charles D’Oyly’s fascinating album provides a rare glimpse into a unique artistic partnership, and a chance to reflect on a chapter of global history that is often hidden. It will be displayed in Out of Time for six months from September 2023, with pages changed every few weeks and full contents viewable on a small screen. We are grateful to the album’s owners for enabling us to appreciate its extraordinary contents.