Everythingism

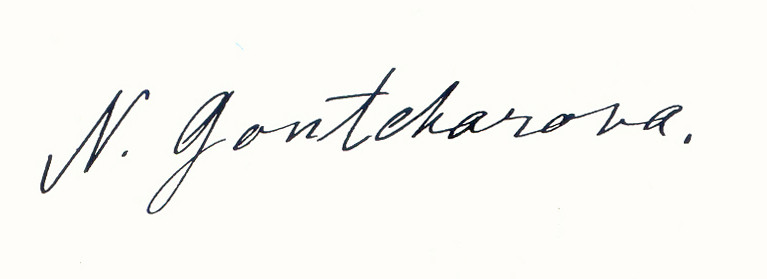

In 2019, the Tate Modern staged a solo exhibition of the work of Russian artist Natalia Goncharova. It was the first time the artist had had a major retrospective in the UK, and the exhibition included her paintings, prints, costume designs and textiles. The exhibition presented reviewers with a twinned challenge: how to talk about an artist who was so little known in the UK, and one who was a woman?

Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov on the background scenery for the opera-ballet The Golden Cockerel in the workshops of the Bolshoi Theatre, Moscow, 1913. Anonymous photographer from the Russian Empire (before 1917). Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

A quick google of reviews of the show reveals the rhetoric that we can expect when the art historical canon celebrates female artists. There is a lot of writing about her relationship to cubism, to fauvism and to futurism – the familiar structures of Western modernism. The show was a “resurrection of Goncharova’s genius”, wrote the Guardian, and Goncharova was, “ripe for rediscovery and reappraisal”, said the reviewer in Apollo Magazine. Artdesk.com effused, “at last the achievements of great women are being acknowledged and celebrated”, and Artsy.net said that the show, “seeks to reinstate Goncharova as the leader of the Russian and international avant-garde”.

I didn’t see the show, so I can’t speak as to whether this was the curators’ intention, or if these reviews were off the mark, but the discussion is familiar, as women artists are now regularly being ‘rediscovered’ and ‘reappraised’ in galleries with exhibition histories and programmes long dominated by men. This rediscovery often falls back on the art historical paradigms of leadership, centring and artistic influence that, to me, always feels unsatisfactory or reductive when discussing women artists in the male-dominated twentieth century, and further back in time.

Would Natalia Goncharova have wanted to be a “leader of the Russian and international avant-garde”? Perhaps. She had the confidence and sense of purpose to flout the societal conventions expected of women in Russian society, even in the tumultuous years of the early twentieth century. In 1913, when she was only thirty-two, she exhibited over 800 of her works in a huge exhibition at the Mikhailova Art Salon in Moscow, and she and her friends at the Moscow College of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture caused a sensation when they paraded in the streets with painted faces and wild costumes to advertise the show.

Goncharova had come to the Moscow College by way of a childhood spent on her family’s country estate in the Tula province, southwest of Moscow. She was born there in 1881 into an aristocratic family whose money came from textile production, though their fortune had been significantly reduced by the late nineteenth century.1 Her family moved to Moscow when she was eleven, and when she was twenty she started taking classes in painting and sculpture at the Moscow College. Here, she met another student, Mikhail Larionov, who became her partner in work and in life, and a strident promoter of her work.

As a student, Goncharova quickly began exhibiting in Moscow’s salons, picking up and discarding interesting ideas from her artistic contemporaries, both in Russia and Europe more widely. Modernism is notoriously obsessed with the new – the next thing, the first one, the major breakthrough – but Goncharova always looked back in time too, using the bold outlines and compositional elements of traditional Russian icon painting and lubok, religious woodblock prints, in her painting and design.

Léonide Massine, Natalia Goncharova, Mikhail Larionov, Igor Stravinsky, Leon Bakst. Ouchy, Switzerland, 1915

Radical avant-garde sensibilities did not make Goncharova and Larionov immune to the politics of Europe in the early twentieth century. Larionov served early in WWI, but was severely injured and spent three months recovering in hospital before he was discharged, to be cared for by Goncharova, who was at the time working for the Red Cross’s war effort.2 In 1915, the pair left Russia for Switzerland to work with Serge Diaghilev and Igor Stravinksy on costume and set design for the Ballets Russes, and early in 1916 Goncharova went with the troupe to Spain, to work on the design for two ballets, España and Triana.3

These ballets were never staged – they remain unseen projects, explored by artists amidst the maelstrom of Europe at war. They had an impact on Goncharova’s career, however, as she was inspired and intrigued by the forms, colours, and movements of Spanish dance and culture, and went on to make many works based on the motifs she saw. It’s at this moment, in Spain, working on two unrealised ballets, that Goncharova’s story begins to intersect with the collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū.

Art collections really are weird things. They assume a veneer of neutrality hanging on the gallery wall, when really they are assembled through the foibles and interests and grudges of fickle humans – they travel through relationships, off-the-cuff decisions and serendipitous encounters, and speak to places and experiences far away.

So, how did this collection of Goncharova’s prints find their way to Ōtautahi Christchurch? Goncharova and Larionov moved to Paris, where they became permanent émigrés after the 1917 revolution meant they couldn’t return to Moscow. In Paris after the war, they staged an exhibition of their work for the theatre, L’Art Décoratif Théâtral Moderne, which included a portfolio of prints, produced in an edition of 500, of which 100 were signed.4 One of these signed collections was given to a young Russian friend of the artists, Valdemar Muling.

Muling and his wife Anita later lived in Manchuria and then, displaced by the Chinese Communist Revolution, moved to Christchurch in 1949. In 1979, Anita Muling gifted the collection of prints by Goncharova and Larionov to the Robert McDougall Art Gallery.5

These aren’t the only works by Goncharova to have made their way into an art collection in Aotearoa; Te Papa also has a number of her paintings. Several years ago I was wandering in a collection exhibition there and I walked past Goncharova’s Scene in an Orchard (c. 1908). I couldn’t stop looking at it. I loved its heavy outlines and wild colours. Goncharova’s work is in Te Papa because of the acuity of Mary Chamot, a Russian-born art historian and assistant keeper at the Tate Gallery, who, between 1965 and 1975, advised the National Art Gallery in Aotearoa on the purchase of European art. This was mostly British art, but, in the 1970s, Chamot, who would go on to write several books on Goncharova (then almost entirely unknown in England) organised for three early works by the artist to be given to the Gallery, and later, gave four more from her own collection.6

These moments in art history always catch my eye: when women are interested in the art of other women, and manage to slip them into the channels of discussion and dissemination; it feels like a gift, a trick of the hand, a potent offering to the future. There’s something compelling and powerful to me in this moment of appraisal, between artist and curator, or artist and viewer, because it’s not a ‘reappraisal’ or a ‘rediscovery’ or a ‘resurrection’, as we have come to understand these words in contemporary curating. I want to know what it was like, in those moments, just to look at a painting, and know that it was good, and important, and created by a woman.

I wonder what Goncharova would make of her works being exhibited in Aotearoa? I like to think she’d be pleased and interested. She was always a strident nationalist and maintained her interest in the traditional arts of Russia, but like other modernists, she was also excited and inspired by the possibilities of the future. After her huge 1913 exhibition in Moscow, the term ‘everythingism’ was coined (in Russian, vsechestvo), to try and describe the ambition and range of her work, and its voracious movement across set design, painting, prints, fashion and illustration.

The vibrant print Costume Espagnole (1919) in Christchurch Art Gallery’s collection captures something of this restless movement. This work began in the mantillas and dresses of Spanish dancers that captivated Goncharova while she was working on ballet designs for Diaghilev. It started in a dance, and was preparation and research for costumes for ballerinas, and then became a print, which then, in turn, became a large oil painting, Espagnole (c. 1916). Goncharova’s work won’t settle down, and from the print’s inception it has been on the move, across time and space, to be here, in the Gallery’s collection today.