Christchurch and the New Zealand Wars

Brett Graham The Great Replacement 2022. Yellow cedar. Courtesy of the artist

It is often assumed that the nineteenth-century New Zealand Wars fought between the Crown and various groups of Māori were exclusively a Te Ika-a-Māui North Island story. But in addition to the violent clash that took place at Wairau, Marlborough, in June 1843, there is a much deeper, if largely unknown, history of southern engagement with these conflicts. Military settlers were recruited from Te Waipounamu South Island goldfields to fight in the Waikato and elsewhere during the 1860s in return for a share of the confiscated lands, and Ōtautahi Christchurch politicians such as Henry Sewell and James Edward FitzGerald were members of colonial governments that were responsible for directing the later military campaigns and land takings, even while they expressed doubts about the justice of what was unfolding.

There is another aspect to this story with a particular focus on Taranaki. Beginning at Waitara in March 1860, Taranaki Māori were subjected to a relentless series of invasions and attacks that continued to play out more than two decades later. As successive governments sought to implement a policy of “creeping confiscation”, it was at different points considered useful to remove Māori from the area.1 The Chatham Islands had previously been used to imprison Māori from the Tairāwhiti (East Coast) region. When it came to Taranaki Māori, Te Waipounamu was selected instead.

In November 1869 a group of seventy-four men from the Pakakohi tribe in Taranaki, convicted of treason for resisting the confiscation of their lands under the leadership of the prophet Riwha Tītokowaru, were sent to Ōtepoti Dunedin. They were sentenced to hard labour and put to work constructing roads, school playing fields, and even improvements to the Octagon, but in the harsh and unfamiliar climate many of the group became ill; eighteen men had died during their captivity in the south before the government finally agreed to commute the sentences of the survivors in 1872. Returning north again aboard the government steamer Luna in March of that year, the party made a stopover at Ōhinehau Lyttelton. More than fifty of their number travelled by train to Christchurch, where their appearance was said to have startled several shopkeepers and “caused considerable speculation amongst the citizens”, despite their “modern civilian attire”.2

John Patrick Ward Tohu and Te Whiti 1883. From John P. Ward, Wanderings with the Maori

Prophets Te Whiti and Tohu ... from their arrival in Christchurch in April 1882 until their return to Parihaka in March 1882, Nelson, Bond, Finney & Co., 1883. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/23012974; /records/23110535

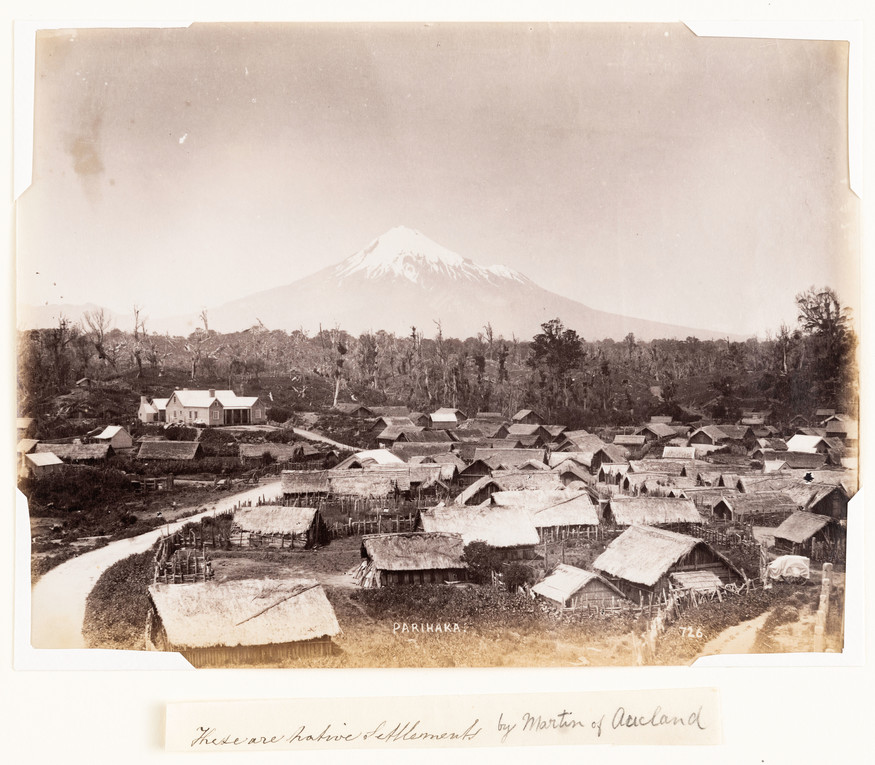

Seven years later, another group of Māori political prisoners from Taranaki was sent south. In 1879 the government pushed through with a survey of lands that had been nominally subject to confiscation fourteen years earlier, but were in practice occupied and used by Māori. That May, the people of Parihaka began ploughing up surveyed lands in the area in an act of non-violent resistance led by prophets Te Whiti-o-Rongomai and Tohu Kākahi. They had founded the settlement of Parihaka in the 1860s as a place of refuge for all those affected by war and confiscation and soon attracted supporters from Taranaki and beyond. But the actions of the Parihaka ploughmen drew an angry response from settlers in the area and by June the government began arresting them. Denied trials, the prisoners were instead sent to Dunedin.

The people of Parihaka remained undeterred. By June 1880 the ploughmen had been replaced by fencers. They, too, were promptly arrested and imprisoned in the South Island without trial. This time there were too many to send to Dunedin alone. While some were taken south to Otago, around forty were imprisoned at Hokitika. And in September 1880 approximately 160 of the prisoners were taken to Whakaraupō Lyttelton Harbour and imprisoned on the small island of Ripapa. In December it was reported that many of the prisoners had been punished for being “unruly and defiant” by having their daily rations reduced to bread and water.3 Meanwhile, within weeks of their arrival, at least one local firm was advertising special excursion trips down the harbour designed to “afford persons an excellent opportunity of viewing the Maori prisoners at Ripa Island”.4 Māori misery had become a Pākehā spectator sport: price 1 shilling and 6 pence per passenger.

Josiah Martin Parihaka c. 1880. Albumen silver photograph. Collection of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased 1997

It is not known exactly how many Taranaki prisoners died during their captivity on Ripapa Island. Buried on Ōtamahua Quail Island, where there were hospital facilities, they were later reinterred at Rāpaki by members of local Ngāi Tahu hapū Ngāti Wheke.5 For them, Ripapa Island (which had been used by the government as a quarantine station since 1873) was a wāhi tapu because of the many people killed there during the Musket Wars of the 1830s. In January 1881 the remaining 149 prisoners were moved from Ripapa to Lyttelton Gaol in order to “subject them to more rigid restriction”.6 Small groups of prisoners were released in batches over the following months and by June the last of them had been freed.

Back home at Parihaka, prophets Te Whiti and Tohu were no more willing to end their campaign of non-violent resistance to the confiscation of 1.2 million acres of Taranaki lands. The Crown’s response came on 5 November 1881 when, led by Native Minister John Bryce riding a white charger, nearly 1,600 members of the armed constabulary and volunteers (including some from Christchurch) invaded the settlement. One journalist who witnessed proceedings reported that “The whole spectacle was saddening in the extreme; it was an industrious, law-abiding, moral and hospitable community calmly awaiting the approach of the men sent to rob them of everything dear to them”.7 Te Whiti, Tohu and several others were seized without resistance and the remainder of the population forcibly dispersed. Many women were raped and the settlement was pillaged and destroyed.

After an inconclusive trial in Ngāmotu New Plymouth, where Te Whiti and Tohu were accused of “wickedly, maliciously, and seditiously contriving and intending to disturb the peace”, it was decided to send the prophets south to Christchurch.8 Theyarrived at Lyttelton on 26 April 1882 to a large crowd of spectators, and were immediately transferred to Addington Gaol, where they were held in the women’s section. Plans to put the prophets on trial again in Christchurch were soon jettisoned. Instead, the pair were held under what one historian describes as “a form of honourable restraint” and another as “a gentlemanly kind of house arrest”.9

Brett Graham Maungārongo ki te Whenua, Maungārongo ki te Tangata 2020. Wood, paint and graphite; Brett Graham O’Pioneer 2020. Wood and plaster. Both courtesy of the artist

An Australian-born Irishman named John P. Ward, who had served in some of the most brutal campaigns in Taranaki and picked up some ability in te reo Māori during his time in the north, was appointed as interpreter and personal jailer to Te Whiti and Tohu (though he never told them of his military service). Ward subsequently wrote Wanderings with the Maori Prophets, a colourful if unreliable narrative of the eleven months he spent accompanying the two men before they were finally permitted to return home to Taranaki in March 1883.

Accompanied by Ward, Te Whiti and Tohu were taken to multiple sites across Christchurch and Canterbury, each designed to impress upon them the wonders of western civilisation. One of the first places visited was Canterbury Museum, where the prophets were met by curator Julius von Haast. From there, they travelled across to Christ Church Cathedral, ascending the tower as far as the bells to take in a panoramic view of the settlement below them. Both men were said to have gazed longingly towards the sea visible at a distance. Visits to the Kaiapoi woollen factory, to the theatre, Addington railway workshops, Hagley Park and elsewhere followed.10 Later asked to name a favourite place visited, Te Whiti opted for somewhere simpler, calling the Ōtākaro Avon River the highlight of his stay.

Te Whiti and Tohu happened to be in Christchurch during the International Exhibition, a three-month long showcase of science, technology, commerce, art and civilisation that attracted an estimated 226,000 visitors. There and elsewhere in their travels, the pair attracted a large and often admiring crowd of their own, many following the men as they inspected the art gallery, waxworks, ‘Ladies Court’, ‘Maori Court’ and other exhibits.11 At least one report noted that some of those who had turned out to see the rangatira were Māori.12 The warm reception they were receiving prompted the New Zealand Herald to complain that “Christchurch people are having the gratification of lionising Te Whiti and Tohu, all at the Government expense”.13

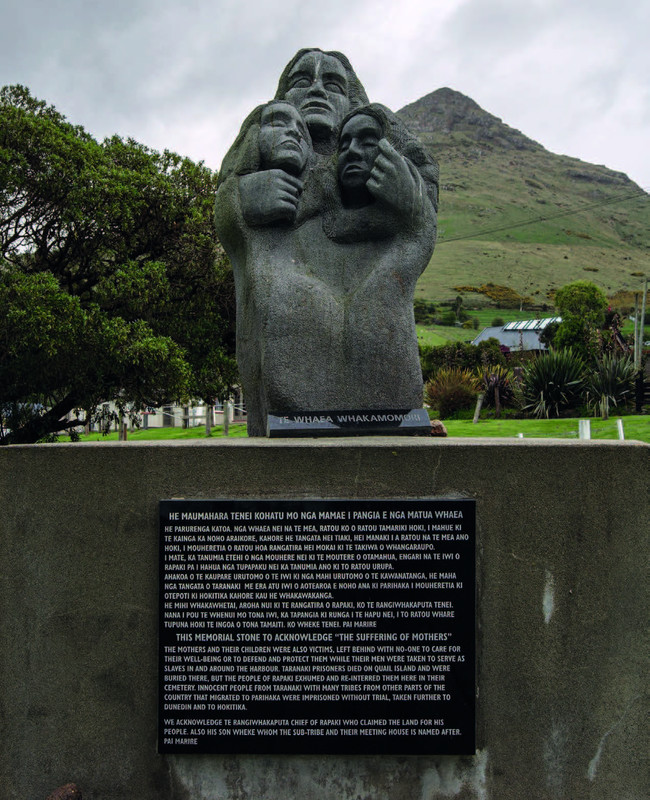

The two Māori prophets travelled much further afield during their stay in the South Island – including journeys to Hakatere Ashburton, Temuka, Timaru, Oamaru, Dunedin, Tāhuna Queenstown, Waihōpai Invercargill, and around to Te Tai o Poutini the West Coast on steamer, followed by six months housed in Whakatū Nelson. But it seems doubtful if Te Whiti and Tohu came away from their extended stay in Te Waipounamu with any sense of the supposed superiority of Pākehā culture. Upon their return to Parihaka the two men immediately threw themselves into rebuilding the settlement into the vibrant and thriving place it had once been, prior to te rā o te pāhua (‘the day of the plunder’) in November 1881. Te Whiti and Tohu had never rejected Western technology or ideas – Parihaka went on to become one of the first settlements in New Zealand with electricity and street lighting – and in this respect their detention in Christchurch and elsewhere in the South Island had not fundamentally altered their outlooks. But it was a compelling chapter in the story of the New Zealand Wars in Te Waipounamu. Today those connections are acknowledged by Ngāti Wheke and the wider community with annual remembrance services at Rāpaki each 5 November, close to a memorial to those held and imprisoned on nearby Ripapa that was unveiled in March 2000, when a 300-strong hīkoi from Taranaki travelled to the settlement.

The Parihaka monument at Rāpaki urupā