A Fireside Whodunnit

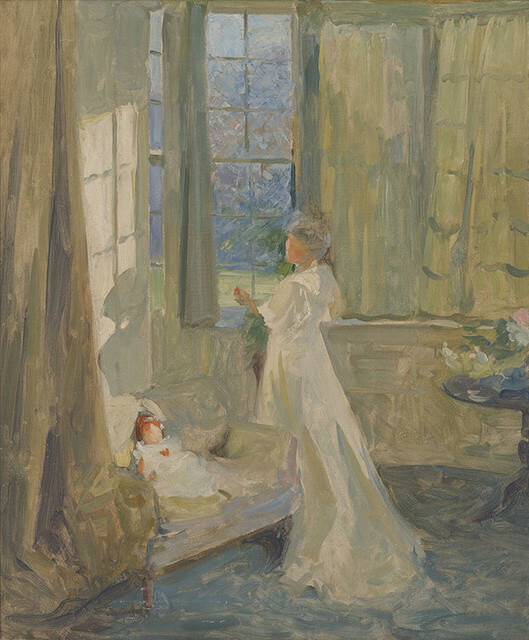

Elizabeth Graham Chalmers Father’s Tea (detail) 1891. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of Caroline Cameron, granddaughter of the artist, 2020

Father’s Tea entered the collection as an unexpected and welcome gift in 2020, together with a small portrait sketch and a larger interior scene by the same artist, both signed ‘EC’. Given by the granddaughter of artist Elizabeth Graham Chalmers (1870–1951), the paintings were old and well-travelled, needing the kind of care that galleries can provide. Father’s Tea also presented an intriguing puzzle around authorship, which has only recently been firmly re-established. As our research continued into 2021, local conservator Olivia Pitts undertook cleaning and repairs in preparation for its inclusion in the 2021–22 exhibition Leaving for Work. This included the removal of old varnish, infilling, and repainting areas of loss, and saw its strength vibrantly reinstated. Completing the restoration was the expert repair and re-gilding of the original ‘Watts profile’ frame by framing conservator Anne-Sophie Ninino.

The lead actor in this charming composition is the girl kneeling in profile by the coal range, a compact study in tones of salmon pink and chocolate brown, her auburn hair offsetting the burning coals. Petite hands on the bellows encourage the glow, subtly reflected in the warming teapot; nestled in front of it is a black kitten whose skewed likeness also appears in the glazing. With the overall composition dividing into bold, near equal halves of light and dark, a dusty kettle emerges from the darkness at left, set to boil on the cast iron stove. Father is evidently nearby. In the subtle still-life arrangement of white on white behind the girl are two teacups, large and small, as well as saucer, sugar bowl and china milk jug, merging with the tablecloth into the pale blue-tinged wall. Father’s Tea is a highly skilled and complex work that seems to open a window into everyday domestic life. It also holds concealed tales of family connections.

There appeared at first two possible contenders for the maker of this work, and acceptable reasons to question the inscription at bottom right, ‘Elizabeth Graham’, as a signature. One was that this painting was unlike any known examples of the work of Elizabeth Graham Chalmers, who had painted sporadically across several decades, held her first solo exhibition in 1928 aged fifty-eight, and became best known as a flower (and occasional London society portrait) painter from that time on. The painting is late Victorian and indicated experience – it seemed difficult to envisage Elizabeth developing such a skill by her late teens or early twenties only then to keep it largely hidden. The painting also strongly resembled the work of Elizabeth’s brother-in-law, leading Newlyn School painter Frank Bramley (1857–1915), who first met the Graham family in Cornwall sometime between 1884 and 1887.1

Elizabeth Graham Chalmers Father’s Tea (detail) 1891. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of Caroline Cameron, granddaughter of the artist, 2020

Elizabeth Graham Chalmers The Oboe c. 1916. Oil on canvas. Gift of Caroline Cameron, granddaughter of the artist, 2020

Elizabeth was born in 1870, so it seemed plausible that this was a painting of her at about fourteen by Frank, painted soon after he reached Newlyn from Italy in the winter of 1884/85, thereby making the inscription an identifying title. It emerged that her parents John and Jane Graham enjoyed commissioning artworks. And the practice of inscribing a sitter’s name was not anomalous in this period: Frank added a similar inscription to a portrait of his wife Katharine – Elizabeth’s sister – in 1896. The handwriting was also similar to his: it was possible to check it against his signature on the large 1908 painting of Elizabeth and her daughter, Helen Graham Chalmers and her Mother, given to the Gallery by bequest from the same family in 1990.2 But why no signature on this one?

The thought that this was Frank’s grew stronger when comparing it with works he painted in Newlyn from 1885 on, evidently in the same room. His Primrose Day (1885) includes what appears to be the same white china jug, with a similar sense of composition and distinctive square brush treatment, and the same technique of merging dark into light between figure and wall. Another painting, Winter (1885), pictures what looks like the same cast iron coal range with identical fireside trivet teapot holder, and bellows hanging on a wall.3 The coal range reappears in Every One His Own Tale (1885), a picture of Cornish fishermen and a young girl seated by a hearth.4 Frank’s Domino! (1886) shows two young women seated at a table playing the eponymous game and has a similar approach to arranging and dividing space in the use of verticals, horizontals, angles and foreground treatments.5 In common with all of these, the hearthside painting carries the sense of psychological weight and interior space – even sense of melancholy – found in Frank’s early Newlyn works. Two well-known paintings – Saved (1889) and For of such is the Kingdom of Heaven (1891) – also include a similar looking young girl with auburn hair in profile, appearing almost a leitmotif.6

All of this seemed to point to Frank, as did comparison with other examples of Elizabeth’s work, including the other newly gifted painting, The Oboe (1916). This attractive work, also needing conservation, pictures a private musical performance in an upper–middle–class interior, and includes the bright young face of Elizabeth’s daughter Helen, who later moved to New Zealand.7 It also displays a different, more free-flowing, painterly technique, closer to that seen in her later flower paintings. The paint treatment is thinner, much of it single layered, sometimes overlapping, and its overall psychological tone and approach to using space are different.

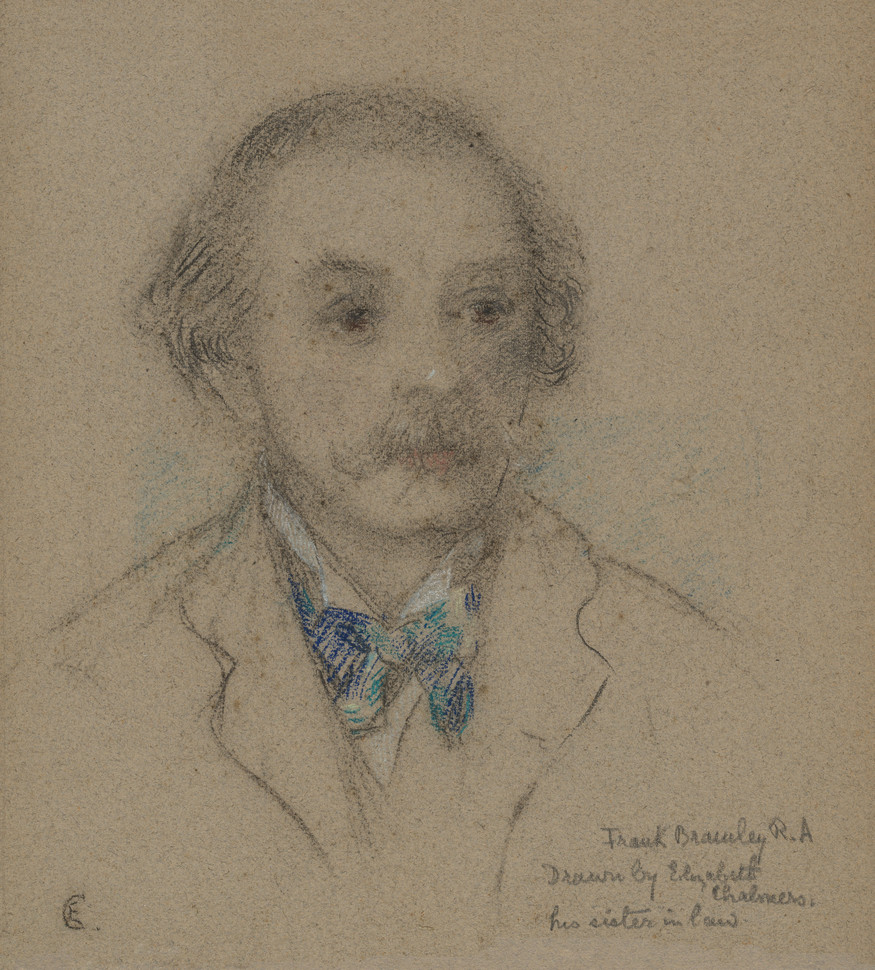

Elizabeth Graham Chalmers Portrait of Frank Bramley c. 1911. Pencil and pastel on paper. Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of Caroline Cameron, granddaughter of the artist, 2020

Frank Bramley Elizabeth Graham Chalmers 1908. Charcoal and pastel. Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, Mr D. M. R. and Mrs H. Cameron Bequest, 1990

Elizabeth’s apparently modest early output also seemed to weigh against her. In 1900 she had married Charles Chalmers, a Scottish paper manufacturer who was knighted by George VI in 1918 and died in 1924. Lady Chalmers’s 1928 exhibition catalogue, from her first professional show, disclosed that “in her 24 years of very happy family life in Scotland, she only painted by fits and starts, often letting years pass without touching a brush,” and lightly mentioned her earlier spending “a winter in Paris studying in one of the Julian studios”.8 The brief essay mentioned that “Frank Bramley R. A. was her brother-in-law and he always encouraged her and thought she ought to take her painting more seriously; until now opportunity was lacking.” It also mentioned that she had “very occasionally exhibited portraits at the Edinburgh Academy, where her work has been very well hung.”

Taking this late cue from the 1928 catalogue, it was necessary to check the Scottish Royal Academy’s exhibition records. Three entries down from Marc Chagall, we find that Lady Elizabeth Chalmers had exhibited five works in total in 1904, 1907, 1924 and 1945 – not a prolific output. Before her marriage in 1900, Elizabeth Graham had shown three works, in 1891, 1895 and 1897. In 1891, her address was ‘Newlyn, Cornwall’, and the first work she exhibited was Father’s Tea.9 This was the twist we did not see coming; the turn that immediately dismantles the Frank Bramley argument. Of course, this painting had to have been exhibited somewhere, and what else could it have been called? Or testing this from another angle, for a moment not accepting it as hers: what would a work titled Father’s Tea, painted by Elizabeth Graham in Frank Bramley’s studio in Newlyn in 1891, look like? The answer is that it would likely look exactly like this, particularly if it was made under his personal instruction, encouragement and watchful eye, reflecting the kind of training he had earlier received in Europe.

While the painting reflects Frank’s influence, it is Elizabeth’s, painted in the period prior to Frank’s marriage to her sister Katharine Glenny Graham (1871–1936) – also said to have been studying to be a painter. Frank and Katharine married in October 1891 at St Pol de Léon’s Church, the parish church of Paul, half a mile from the Old Manor Farmhouse in Trungle where the Grahams were lodging with a local farmer on the night of the April 1891 census. This was the same time as Father’s Tea was exhibited in Edinburgh, and suggests that the family’s stay near Newlyn was prolonged. The young sitter in the painting was possibly the youngest Graham daughter Georgina Margaret (Madge), who later also became an artist.10

Frank Bramley Helen Graham Chalmers and her Mother 1908. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, Mr D. M. R. and Mrs H. Cameron Bequest, 1990

The direction of the encouragement given and taken shifted between Frank Bramley and Elizabeth Graham Chalmers in the years after her marriage. She and her husband became Frank’s major patrons, assisting him and Katharine through financially difficult years and commissioning many family portraits up until a few years before his death in 1915. These include the large Helen Graham Chalmers and her Mother, shown at the Royal Academy in 1908, and Helen, Daughter of Charles Chalmers Esq [also known as Flowers for Nanny], shown in London in 1910, another work awaiting conservation treatment.

Father’s Tea, painted when Elizabeth Graham Chalmers was twenty or twenty-one, is her earliest known exhibited work, from the beginning of an uncertain painting career. That she was an artist of potential was recognised by the Glasgow Herald art critic: “‘Father’s Tea’, (No.434), by Elizabeth Graham, while a trifle finicking and immature, is a picture of promise, in its careful detail and tenderness of feeling.”11 The identification and reattribution has been a vital part of the restoration process, and confirms its place as an exciting addition to the collection.12