Te Aue Davis (Ngati Maniapoto, Ngati Uekaha) Kakahu (detail) c. 1980. Whito (muka), feathers from kiwi and pukeko. Collection of Ta Tipene O’Regan

Te Puna Waiora

Aligning the Threads of Kāhui Whiritoi

In the Māori worldview, context is vital. Knowledge is not disembodied information but part of a living matrix of encounters and relationships, past and present, natural and spiritual.1

Te Puna Waiora is the most significant showcase of Māori weaving to be displayed in Christchurch since the Gallery hosted the homecoming of a major international touring exhibition early in 2007. That exhibition, Toi Māori: The Eternal Thread / Te Aho Mutunga Kore, was the first of its kind and had returned from touring in the United States to great acclaim, reaching audiences of over 50,000 people as well as capturing the interest of the US media. It celebrated the changing art of Māori weaving, featuring traditional and contemporary work by more than forty leading Māori weavers, some of whom are still weaving today.

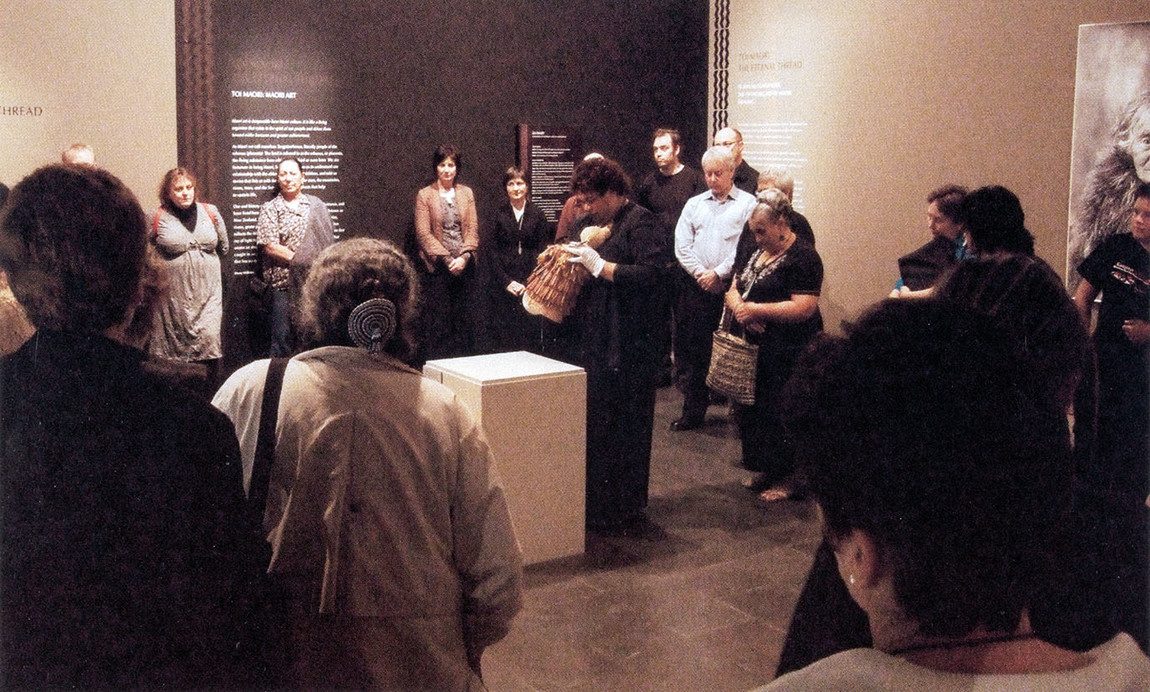

It was an emotionally charged moment of the Eternal Thread closing ceremony on 27 May 2007, when Puamiria Parata-Goodall uplifted the late Cath Brown's Kaikaranga figure, as Cath had been a key planner of the exhibition from its initial concept.

Some of the Aotearoa weavers who responded to a call from Norfolk Island weavers in 1994. At left: Te Aue Davis, from centre to right: Cath Brown, Emily Schuster, with Lydia Smith beside kaumatua Canon Rua Anderson, with four other supporters. The group travelled to Norfolk where they held workshops, demonstrations, talks and an exhibition. Image: Aotearoa Moana Nui a Kiwa Weavers. July 1994, No.20, ISSN 1171-3593

To truly appreciate the new exhibition, Te Puna Waiora, it is essential to have some understanding of the process of Māori weaving; of its devastating decline during nineteenth-century colonisation, and its eventual recovery. Further to this is the need to understand that, for Māori, knowledge is inseparable from its context.For generations, all the basic daily requirements of the Māori people – food, clothing and shelter – were met through their close working relationship with the land and its resources. Working with harakeke (Phormium tenax), now commonly known as ‘flax’, was a key factor in this. The weaving practices of whiri (twisting fibres), whatu (twining) and raranga (weaving/ interweaving) were acknowledged taonga (treasures) received from the ancestors. Expert kairaranga (weavers) were valued members of their communities. Every settlement had a nearby pā harakeke, for its uses were many and varied. What use is a fishhook without a line? Who can build a house or a waka without an adze? How do you make an adze without cordage to lash the blade to the haft? What do you use for raincapes? How do you carry foodstuffs? Māori not only grew a variety of different cultivars for the diverse properties of their leaves, such as strength, softness, colour and fibre content, but they also identified multiple uses for virtually all parts of the plant – flowers, stalks, gum, rhizomes and more.

Small wonder then that flax became the most important fibre plant to Māori in New Zealand. When William Colenso (1811–1899) told Māori chiefs that harakeke did not grow in England, their responses were telling: “How is it possible to live there without it?” and “I would not dwell in such a land as that.”2 However, with the coming of missionaries, settlers and colonial governance, a cash economy and significant loss of their lands, the nineteenth century brought massive changes to the Māori way of life; before the century had ended, Europeans were fully anticipating the demise of the Māori race. Time-consuming arts such as traditional weaving fell by the wayside.

Weavers gather for the powhiri of the biennial National Hui at Maraenui in 2007. Photo: Patricia Te Arapo Wallace

Despite this, and after two world wars and escalating Māori urban migration, by the mid-twentieth century things were beginning to change again. Māori and Pākehā began to learn more about each other as a new generation of urban Māori, educated and articulate young individuals, began to raise public awareness of Māori issues for the first time in a century. The 1970s saw the beginning of a Māori renaissance that included the revival of te reo Māori, the land-focused Māori protest movement, increased interaction with other indigenous peoples, and the critical Te Māori art exhibition (1984–87). This watershed exhibition of Māori taonga was the first occasion on which Māori art was shown internationally as art; it incorporated practices and values guided by traditional tikanga. Opening in New York, it toured St Louis, Chicago and San Francisco before returning to tour New Zealand. It was a huge success and an enormous source of Māori pride, and it awakened New Zealand’s own media to the nation’s unique Māori point of difference.3 In retrospect, it is seen as a milestone of the Māori cultural renaissance.

Although no woven taonga were included in the Te Māori exhibition (textile artefacts being notoriously fragile), it was against the background of exhibition preparation that moves to ensure the renaissance of woven arts were proceeding. In 1983 the Māori and Pacific Island Arts Council (MASPAC),4 invited ten women to meet in Rotorua to consider the needs of weavers in Aotearoa. They formed a steering committee, with New Zealand Māori Arts and Crafts Institute (NZMACI) weaving tutor Emily Schuster (1927–1997) as convener. It was unanimously agreed that a hui would enable weavers to develop their ideas; another well-known renaissance leader Ngoi Pēwhairangi (1921–1985) offered to host such an event at Pākirikiri Marae, Tokomaru Bay. MASPAC funding enabled weavers from around the country to attend; 160 were anticipated, but more than 400 came. This was the beginning of Aotearoa Moana-Nui-a-Kiwa Weavers. Over the next ten years, the sharing of techniques and ideas at regular hui saw the group become a major force in the development of Māori art. But in 1989, the Craft Panel of the Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council gave financial assistance for two particularly significant hui. The first, at Rapahoe, north of Greymouth, was for invited members, experts in their field who were often so occupied with teaching others that they had little chance to sit and work with their peers. The second, held at Waiariki Polytechnic in Rotorua, focused on contemporary weaving, giving weavers opportunities to experiment in ways they may not have attempted previously.

Te Aue Davis (Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Uekaha) Te Aroha o Te Aue Davis 2010. Whito (muka),

feathers from kiwi and weka. Collection of Ta Mark Solomon

Weavers continue to learn from members of Kāhui Whiritoi who work among them at the National Hui in 2005. Photo: Patricia Te Arapo Wallace

In 1994, arts council restructuring saw changes of funding occur. Consequently, Māori and Pacific weaving groups parted, and a new Māori weavers’ collective evolved – Te Roopu Raranga Whatu o Aotearoa (TRRWOA). The Roopu’s national hui held biennially over Labour Weekend at different marae around the country became an important part of the group’s growth and achievement, but that success brought its own problems. The enthusiasm of less experienced weavers again precluded opportunities for master weavers to work together, as they had done at Rapahoe.5

It was not until 2005 that Edna Pahewa was able to fulfill the longstanding wish of her mother, Emily Schuster, to acknowledge the mana of our master weavers appropriately. In her joint capacities as chair of TRRWOA at the time, and tumu raranga (head of weaving) at NZMACI, she oversaw the inauguration of a new group, the Kāhui Whiritoi. Members are required to have contributed to Māori weaving locally and or nationally for forty years or more; appointments continue to be made by the NZMACI tumu raranga, and the chairperson of TRRWOA.

Learning continues at the National Hui in 2007. Photo: Patricia Te Arapo Wallace

The initial Kāhui Whiritoi members were Saana Murray (1925–2011), Diggeress Te Kanawa (1920–2009), Riria Smith (1935–2012), Whero Bailey (1936–2016), Te Aue Davis (1925–2010), Waana Davis (d.2019) and Eddie Maxwell (1939–2009). Founding members who passed away before the group was formed, Emily Schuster and Cath Brown (1933–2004) are also acknowledged. Current members are Matekino Lawless, Toi Te Rito Maihi, Ranui Ngarimu, Reihana Parata, Connie Pewhairangi-Potae, Mere Walker, Sonia Snowden, Pareaute Nathan and Christina Wirihana.

So now the threads are aligned, and we have come full circle, because although there are currently many weavers and weaving groups around the country, and the skills are no longer at risk, these special kairaranga link us inextricably to the weavers of the past. Most of them learned ‘the old way’ (or learned from weavers who had) – starting their day with karakia, setting off to harvest harakeke for whanau needs, watching and learning from whānau members, and working together. All are utterly grounded in te ao Māori, in tikanga Māori, and in the broader needs of whānau, hapu and iwi. More than just weavers, they are environmentalists, historians, artists, teachers. They inspire and share their knowledge with others. And invariably, all are incredibly humble.

Te Punga kua tau, e mau ai te Aho. The anchor is settled, holding fast the thread.

The anchor represents our ancestral weavers, whose spiritual presence moves among us although they have gone, and who return to rest in peace, knowing that the threads (i.e., the next generation) are well secured.6

Current members of Kāhui Whiritoi (from left): Sonia Snowden, Connie Pewhairangi, Reihana Parata, Matekino Lawless, Ranui Ngarimu, Toi Te Rito Maihi, Christina Hurihia Wirihana, (absent: Pare Nathan). Te Puia, Rotorua, 2020. Photo: Toi Māori Aotearoa