Touching Sight

Conor Clarke, Emma Fitts, Oliver Perkins

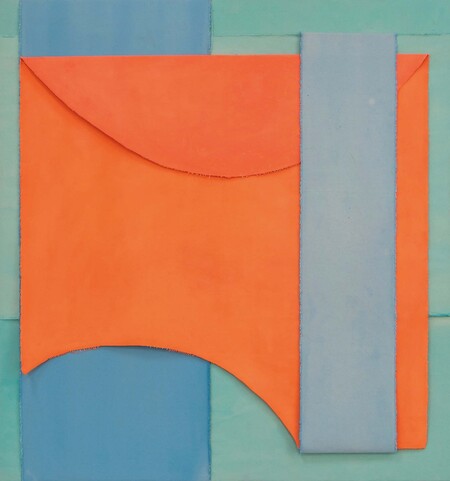

Emma Fitts Chequered / Scooped (detail) 2020. Acrylic and Flashe on canvas. Courtesy of the artist and The National, Christchurch. Photo: Sarah Rowlands

Working in photography, textiles and painting, Conor Clarke (Ngāi Tahu), Emma Fitts and Oliver Perkins explore ideas of perception, both how we gain awareness through our senses, and the way in which something is interpreted or understood. Bulletin invited three writers to respond to the work in progress, to consider the materials and ways of making that each artist utilises. The resulting texts from Abby Cunnane, Fayen d’Evie and Chloe Lane are exploratory themselves, and offer us new ways of thinking about the works they relate to – as sensory items, as skins, as lichen.

Perceiving Nature: Conor Clarke

Conor Clarke Huka Falls (Described by Steve Delaney) 2020. C-type print, braille (PVC, UV ink). Courtesy of the artist and Two Rooms, Auckland

Conor Clarke is troubled by photography that claims too much. Increasingly sceptical of photography’s alliance with documentary objectivity, Clarke has been drawn towards the ambiguities and distortions of sight, and the cultural and aesthetic associations that influence how we perceive and value nature. In one recent work, Waterfall on the Grid (Māngere) 2017, Clarke pointed to the habit of valuing utilitarian landscape features like storm-water overflows as less scenic than apparently untamed nature. State and commercial tourism operators reinforce this cultural doctrine, by endorsing and marketing certain landscapes as emblematic of the nation’s natural beauty. Through Google image searches, Clarke noticed that visitors to such flagship destinations will often capture personal photographic mementos that are near identical to those of the scores of visitors who have preceded them. This is not coincidental. There is a certain satisfaction and sense of belonging that comes with re-performing the trope, in acquiring documentary proof that an individual has been present in a location of collective desire. For a photographer as skilled as Clarke, her conundrum is not technical, but conceptual. How might photography be deployed to provoke audiences to contemplate their natural and built surroundings beyond worn scenic tropes?

In her new body of work, Clarke experiments with a method of producing photographic images from her intuitive response to conversations with blind and low vision collaborators. To de-privilege visuality as the usual source of imagery, Clarke invited her collaborators to describe an experience in nature, as if addressing another blind friend. Steve Delaney recalled a spontaneous memory of a visit to Huka Falls: “Imagine you are under the shower, but the shower has the force of ten thousand showers. The energy is so cold and immense that you cannot survive beneath it. It overwhelms you…” Delaney’s sensorial description punctures the illusion that a scenic snapshot can convey all that is essential to an embodied memory of a particular place.

There is an ingrained cultural meta-narrative that equates blindness with ignorance, demonstrated by ubiquitous metaphors like ‘blind spot’ or ‘blind drunk’. Frustratingly, this pejorative treatment of blindness is also littered throughout art discourse. Consider art historian Michael Fried’s renowned critical text Absorption and Theatricality, which is grounded in an analysis of eighteenth-century Parisian paintings of Blind Belisarius Receiving Alms. Fried concludes that “Belisarius’s blindness, which rendered him unaware of being beheld… could be perceived as an exemplary mode of obliviousness.” Embedded here is the absurd assumption that without sight, a person has no awareness of their surroundings. This false logic merely demonstrates the obliviousness of those who privilege sight to sounds, smells, temperature variations and a myriad of other sensory perceptions that allow social dynamics and landscapes to be read without vision.

As Delaney’s description of the tumbling water of Huka Falls demonstrates, blindness can invite impressions of nature that are nuanced and visceral. Think of a summer breeze whispering at the back of your neck, a southerly squall drenching your body, a mist dampening your face as you walk along a forest track. Of course Tāwhirimātea, god of all the winds and rain and fog, was so angered by his brothers’ collusion to separate their parents Ranginui and Papatūānuku, that he tore his eyes out and cast them into the heavens, where they became the stars of Matariki, Ngā Mata o te Ariki o Tāwhirimātea. These forces of nature are by legend blind, and powerful.

With her collaborators’ descriptions as provocations, Clarke walked nearby her home, allowing intuitive associations to guide her choices of site and subject. She used a pinhole camera with no viewfinder, a choice that diminished her ability to control how content was framed and focused, introducing room for guesswork and happenstance. In past exhibitions, Clarke has drawn on blurring and veils to heighten ambiguity. But here Clarke has resisted aesthetic strategies that might be confused for simulating visual impairment. The resulting photographs are crisp and visually alluring. Yet, due to their clarity, her images cannot be confused for literal representations of the sites described by her blind collaborators, which play within the exhibition space as an audio narration. Clarke thus establishes distance between what might be seen and what might be heard, inviting reflection and trans-sensorial conversation about how we each subjectively experience and interpret the world around us.

Fayen d’Evie is an artist and writer, born in Malaysia, raised in Aotearoa New Zealand, and now living in the bushlands of unceded Dja Dja Wurrung country, Australia.

Lichen is a Contract: Emma Fitts

Emma Fitts Chequered / Scooped 2020. Acrylic and Flashe on canvas. Courtesy of the artist and The National, Christchurch. Photo: Sarah Rowlands

Lichen is a contract. That is, it exists as the result of a relationship between organisms from two, sometimes three different ‘kingdoms’.1 I picture it like this. Kingdom Fungi: slow moving and damp, breathing whiffs of mushroom, compost and yeast from its planty tissue. Kingdom Algae: a loose textile of restless, glinting filaments of light, the air itself turning slightly green as it comes into contact. Sometimes there is bacteria too, Kingdom Monera: single-celled organisms that have no membrane, are almost just a pore, a process. The fungi structure protects the more vulnerable algae – the fungi is what you see when you identify lichen. The algae cells, nested within, do the work of photosynthesis, producing carbohydrates to sustain the whole.2

I spoke to Emma Fitts about her new works in August, and wrote about them,3 mainly the loose canvases photographed along the Port Hills crater rim, Ngā Kōhatu Whakarekareka o Tamatea Pōkai Whenua.4 These works were something like lichen I thought. Lichens are what the bone-hard rock shoulders up there wear – or, they wear each other, the microorganism and the terrain, who is to say?5 The lichen may be wearing the rocks, the rocks wearing the light, which is in turn held close by the photosynthetic lichen. The lichen metaphor, the co-reliant organism, still rests well in my mind – Fitts’s new works too could be thought of as a kind of contract. In the making process, the Flashe and acrylic solution saturates the canvas, holding and bending the light, like algae, so that it emerges acidic and luminous in some works, muted in others. The canvas holds the weight of that process, drying pigment-loaded, a layered or folded structure, starchy as lichen. For weeks now I have seen lichen everywhere, like there is a filter on my eyes.

There is a point when a metaphor changes though, becomes something that you wake up with and can feel on your skin, becomes a garment itself. This is not the first time these works have been thought about as something to be worn. A series of works (initially developed from research while Fitts was resident at McCahon House, Titirangi, in 2017) reference a backstrap loom, which is worn on the body while the weaver works. ‘Worn’ is only an approximate word for this relationship – leaning into the loom backstrap, the weaver’s backbone and chest, at least, are the loom, along with two wooden poles between which the warp is stretched. In Touching Sight, hung from wooden poles, these works still remember the movements of the working body, the twist of a torso and resistance of bone. The slack fall of cotton rope seems ready to be stepped into, become taut again with the working of the maker’s back and arms.

Then there are a series of ‘envelope’ works, referencing the garments of French designer Madeleine Vionnet (1876–1975). Vionnet’s dresses were cut on the bias – following the shape of the body and making redundant undergarments like corsets. Bias cut dresses were easy to get in and out of and to move in, loose envelopes for the body’s structure, which in turn lent them support, volume, blood-warmth. These works seem to rest against the wall, answering only to the diagonal seams and the points at which they are fixed for their form. It’s not that they ‘clothe’ the wall. Rather, the walls and the works lean on each other. Look closely; the air around them almost shivers with that equilibrium.

I’ve never actually been in the same room with this work though, seen it on the walls. Lockdown and the distance between Tāmaki Makaurau and Ōtautahi mean that I have seen it in emailed jpegs only. Maybe this is why the metaphors have been so real to me, as if seeing alone is not, this time, enough. I open up the images of Fitts’s work on my laptop again, zoom in until I find the grain of the canvas and its chalky pigment, in contrast to the gleam of the screen. There is another contract at play. If I angle the light on the screen just right, at the correct diagonal, it’s like the canvases are wet again, soaked in the light from the window by my desk.

Abby Cunnane is a writer and curator based in Tāmaki Makaurau. With artist Amy Howden-Chapman, she is co-editor of The Distance Plan, a journal and exhibition platform focusing on contemporary art and climate change.

Harvest: Oliver Perkins

Oliver Perkins Pots (4) 2020. Ink and size on canvas. Courtesy of the artist, Michael Lett, Auckland and Jonathan Smart, Christchurch

My sister-in-law is a plastic surgeon. One of the things she does is help people grow back their skin after severe burns, traumas, the removal of cancers. “You can pretty much harvest skin from anywhere,” she said. “When you first harvest from the scalp it seems very wrong.”

When she told me this I involuntarily touched my hand to my head. We were sitting in her living room. I thought about how strange it must be to have a part of your body sectioned out, removed with a tool like a large vegetable peeler, and then stitched, stapled or glued on to another part of your body. And what a gift it was to be able to think about the strangeness of this, to be healthy enough to ponder my skin, its potential for redistribution, realignment.

Sometimes she uses cadaver skin. If a patient is burned over 80% of their body, you can’t graft that much body with only 20% undamaged skin. It’s an impossible equation. A lot of the cadaver skins come from outside New Zealand. Often the skin colour match isn’t quite right. But that skin, though it might be imperfect, is there to help the patient heal, to make them whole. It’s always a long process, she explained. The wounds are tended to regularly. If a graft doesn’t take, maybe the wound has healed enough to be simply dressed. Or maybe a new graft is needed. Or maybe a temporary skin replacement, a synthetic polymer, is used instead. The surface of the human body becomes a work in progress.

I wanted to know if she always had an end result in mind, or if the job required her to just take one step at a time and feel it out?

While she talked I looked at the line of thin scraggly plants sitting on the coffee table. Coriander, basil, oregano, mint. The soil dry and hard, lifting away from the edge of the black plastic pots. How many supermarket herbs have I seen in this state, barely clinging to life? It’s something about their roots being too shallow, the pots too small. There’s no room for them to breathe.

“Today,” she said, “I had a skin cancer list where I did skin graft after skin graft. I went into automatic mode and didn’t even think about the process really. If I was doing a trauma case though, I would typically debride the wound, see what’s left at the base and decide how the wound could be reconstructed. It may just need a skin graft. Or more complex operations – flaps, that’s a whole other thing – and I would use the graft for parts of the areas it would take. In this case I have skin graft in my back pocket and use it if needed.”

Though what she is does is very precise and considered, dependent on many years of training, it’s still a mystery, a wonderful kind of magic to me. A skin graft in her back pocket. To be used if needed. Can you imagine?

Chloe Lane is a writer based in Ōtautahi. Her debut novel The Swimmers is out now with Victoria University Press. She has recently had essays published in Pantograph Punch, Contemporary HUM, The Spinoff and Newsroom. She is the founding publisher and editor of Hue+Cry Press.