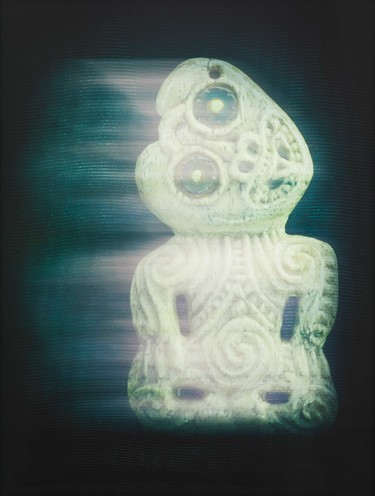

Fiona Pardington A220848 2019. Pigment inks on Hahnemühle Photo Rag. Courtesy the artist and Starkwhite. With thanks to Wellcome Collection | Science Museum Group

Wellcome to Māoriland

London’s Wellcome Collection was founded by Sir Henry Solomon Wellcome (1853–1936) in the year he died. An incredibly successful US-born, British pharmaceutical entrepreneur, Wellcome had a penchant for collecting medical and health-related artefacts, which formed the basis of the Collection. He didn’t restrict himself to the more obvious examples of early medical technology, however, but also collected in the area of folk remedies and indigenous cultural objects, which were largely acquired through London auction houses. Browsing the Wellcome Collection’s online catalogue, Aotearoa New Zealand photographer Fiona Pardington (Kāi Tahu, Kāti Mamoe, Ngāti Kahungunu, Clan Cameron) encountered what at first glance looked to be a number of heitiki; however, on closer inspection they did not seem quite right.

They sit in the uncanny valley between familiar expectations and wrongness. Some are very crudely formed; some are carved from bone rather than pounamu; others bear carving that resembles Celtic knotwork rather than koru and pitau forms; still others appear to sport beards and spectacles. It would be wrong to dismiss them all as forgeries, although some almost certainly are. All borrow the forms of heitiki – the distinctive foetus-like adornment that emerged late in the phase of Māori artistic development that Sir Hirini Moko Mead calls Te Tipunga, “the growing”, of roughly 1,300–1,500 CE. None are heitiki in the true sense of having the mana of being carved by a tohunga whakairo, although some of them may have been carved by tangata whenua for the Pākehā and European markets. Call them ‘tiki’ like you would the plastic ones mass-manufactured for the tourism market. But why were they made and where do they come from?

Fiona Pardington A69170 2019. Pigment inks on Hahnemühle Photo Rag. Courtesy the artist and Starkwhite. With thanks to Wellcome Collection | Science Museum Group

We can probably pin them down to a span of a few decades at the height of the colonisation of New Zealand. In his book Galleries of Maoriland: Artists, Collectors and the Māori World, 1880–1910 (2018), the late Roger Blackley identifies the period as a “curio economy”. During this time Pākehā were attempting to appropriate Māori imagery and cultural property out of a combination of nascent nationalism, exotic fetishism, greed and remorseful salvage; Māori were desperately trying to gain some kind of autonomous control over how they were represented at large, and fending off the theft of their taonga and their relegation to a tourist attraction. This was the time of Gottfried Lindauer and C.F. Goldie, of the founding of provincial museum collections, and a lucrative international trade in indigenous artefacts.

“Maoriland” was the poetic romantic fiction the Victorians came up with for it. Similar to the Celtic Twilight, it appealed to the idea of a “Better Britain” and postcard fantasies of smoothing the pillow of a dying race. Heitiki were an attractive currency in this climate of theft, exploitation and exchange, but they were in limited supply. Early Pākehā souvenir touts and Māori feeling the sting of giving taonga as koha to every important visiting dignitary and celebrity alike, commissioned tiki from the famous lapidary workshops of the German Rhineland. Pākehā of the educated elite were keen to present themselves as connoisseurs of Māori taonga and provided a ready and not particularly discerning (knowingly and unknowingly) market for Māori and Pākehā chancers to knock off something that looked about right. These collections found their way into museum collections. There are, for example, things in the Mair Collection at Auckland’s War Memorial Museum that are no longer displayed for that reason.

Researching the phenomenon reveals a cast of fascinating characters. Renowned Te Āti Awa carver Jacob Heberley (1849–1906) of Petone was a prolific maker in bone for the Pākehā market. And then there was James Frank Robieson (1879–1966). Born in Masterton, he lived in Rotorua for a period then emigrated to Britain in around 1920. He made a career out of forging Māori taonga from materials he had brought with him, before eventually returning to New Zealand to be buried in the town of his birth. In British museum-based anthropology there is a whole subset of scholarship dedicated to distinguishing Robieson’s forgeries from those of another infamous faker, James Edward Little (1876–1953), who never visited the Pacific at all and confined his copying to what he could steal from British museums. Puke Ariki in New Plymouth has some examples of his work.

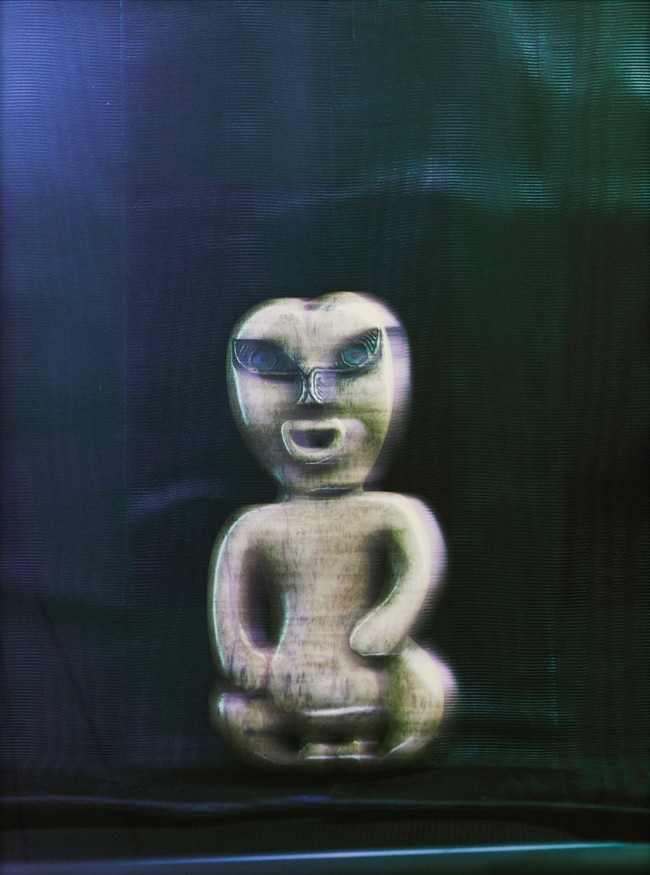

Fiona Pardington A33118 2019. Pigment inks on Hahnemühle Photo Rag. Courtesy the artist and Starkwhite. With thanks to Wellcome Collection | Science Museum Group

The Wellcome tiki are likely a motley mixture of these sources. We don’t know who made them, and the intentions behind their creation are lost in the homogenising vicissitudes of time. They are born out of what the philosopher Bruno Latour calls iconoclash – the uncertainty of the good or bad nature of an image’s degradation or destruction. Pardington, given her own emotional quest to strike a balance in her whakapapa between her Māori and Pākehā-Scottish lines of descent and identity, feels an empathy for these objects.

“The tiki were irresistible, inevitable,” Pardington says. “That’s how I know a particular subject matter is show-worthy. Seemingly adulterated by the crossings of cultures, conquest and capital, anomalous tiki people collections worldwide. Some are hidden away, others which in all likelihood are bastard, souvenir or imposter are contumaciously displayed as legitimate heitiki. Others may be the mahi of junior carvers or earnest but disinformed hobbyists. Were they imagined by sailors with time on their hands or whalers between whales perhaps? A stained ivory tiki that looks like a surprised imp, one a squat elemental or another an elegantly lanky being with two too many fingers (heitiki should have three). Some have eyes like a spinning carousel at night. Each tiki is exclusive unto itself, a melange of astonishment and bewilderment. How could one not photograph within the Wellcome Collection?”1

Pardington’s present project relates to two other bodies of work. The photographer approaches the tiki in a similar spirit to the way she did taonga in museums, using the unspoken contract between the realism of the camera and a visual manifestation of their mana and mauri through lighting and her aesthetic. The result is another taonga, the metaphorical image of an ancestor and an atua rather than merely an artefact gathering dust in a glass vitrine. This process is paralleled in her exploration and self-discovery of her Māori self. We may also look at Pardington’s The Pressure of Sunlight Falling (2011), in which she photographed busts of indigenous people, cast from life by scientist and phrenologist Pierre Dumoutier on French explorer Jules Dumont d’Urville’s 1837–40 South Pacific voyage. By photographing them in a beautiful way, Pardington re-appropriated the busts and rehabilitated them from European science and pseudoscience, and the unpleasant associations of their creation, to reposition them once more in a Pacific discourse.

Fiona Pardington A76460 2019. Pigment inks on Hahnemühle Photo Rag. Courtesy the artist and Starkwhite. With thanks to Wellcome Collection | Science Museum Group

In her book Reparative Aesthetics: Witnessing in Contemporary Art Photography (2016), Dr Susan Best of the University of Queensland groups Pardington’s approach with that of other female southern hemisphere photographers Anne Ferran of Australia, Rosângela Rennó of Brazil and Milagros de la Torre of Peru. Reparative aesthetics is Best’s application of the theories of affect psychotherapy and aesthetics, where artists sugar their challenging political messages with beauty to seduce the viewer into a dialogue feedback loop with the work and message. In Pardington’s case this is heavily mediated by an animistic and pantheistic sensibility, which the Eurocentric art establishment is only now beginning to rediscover, and which German curator Anselm Franke describes as an “undisciplined” form of knowledge. Colonialist capitalism treats persons as things. Animism treats things as persons. Such an approach may be the only way civilisation can heal its rift with the environment and history. Pardington is, to use a word from Guy Debord and the Situationist International, détourning them, repurposing them from popular culture for political purpose.

Fiona Pardington A39559 2019. Pigment inks on Hahnemühle Photo Rag. Courtesy the artist and Starkwhite. With thanks to Wellcome Collection | Science Museum Group

“They want us to know about their present,” says Pardington, “which for us is at best our present reckoning of their previous lives, buffered against the welcome we can genuinely afford their occluded histories. The combined truths of their past experiences are immanent. They speak of the rare and previously unheeded blend of cultural complexities they possess in the face of our inevitable demise and forgetting. They come to us, pass beside us and overtake us. In their status as fugitive beings they call to us, we can anticipate them, experience them fleetingly, remember them as best we can, but they’re impossible to gain the sum of. We can feel their trajectory as we retreat in to the past and they move into a future we can’t populate. We have a given time they are not subject to, though they are not immutable.”2

These tiki might not have mauri and atua in the purest sense, usually understood in terms of tikanga and Māoritanga, but they have a compelling presence, a personality and a being of some kind. Noa rather than tapu, they did not demand to be created, though they demand our attention. Their creation had purpose, intention and some degree of care, and to that end they deserve a degree of respect for their dignity. This is Pardington’s gift to them and to us.

Fiona Pardington A108713 2019. Pigment inks on Hahnemühle Photo Rag. Courtesy the artist and Starkwhite. With thanks to Wellcome Collection | Science Museum Group

This article was amended in October 2020 to correctly represent Jacob Heberley’s iwi as Te Āti Awa. Heberley was misrepresented in the uncorrected article, and we apologise for any offence caused to his descendants.