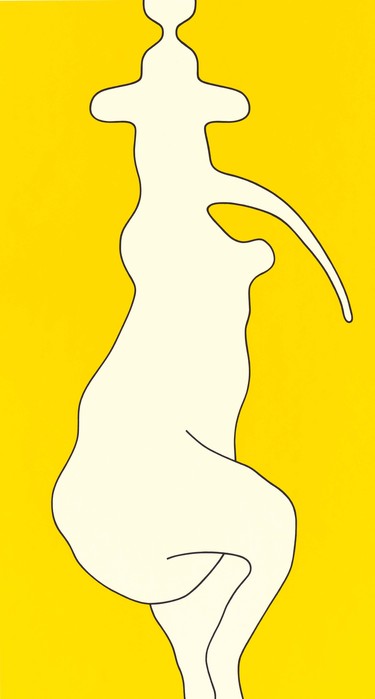

Brent Harris On Becoming (Yellow no. 3) 1996. Colour screenprint. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of the artist, 2018

Appalling Moments and Abstract Elegies

Brent Harris is an Australian artist, well known for a practice that explores the productive tension between abstraction and figuration. By locating emotional content in figures that he develops from automatic drawing, his works frequently express an uneasy human subjectivity. But while his imagery deals with intense psychological states, it is often also darkly funny: monsters of the subconscious, both grotesque and ridiculous, rise to the surface in a process of emotional identification and gradual refinement.

Over thirty-five years of practice he has continually challenged himself, alert to the creative possibilities of chance and intuition. His prints and paintings have been collected by all major Australian public galleries, while significant holdings of his graphic works have been acquired by the British Museum. In 2018, he gifted nearly seventy works on paper to Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū. I’ve been visiting him in his Melbourne studio over the past couple of years, and the Gallery’s first exhibition of his work, Towards the Swamp, opened here in November.

Harris is a New Zealander by birth. Born in 1956, he grew up in Palmerston North and took up a carpentry apprenticeship when he left school; he became interested in art as a possible career after fitting out a small local art gallery. He read voraciously; he met other artists; he produced a portfolio, and left for Melbourne in 1981, graduating from the Victorian College of the Arts in 1984. As an art student, Harris was given regular behind-the-scenes access to the treasures of the National Gallery of Victoria, and spent a great deal of time in the Prints and Drawings Room, studying works by Rembrandt and Edvard Munch, among others. He’s been a regular visitor ever since. His deep knowledge of art history informs his practice: his works are frequently in conversation with those by other artists, across time and place. Munch’s Towards the Forest II (1915) has been a particular touchstone in his practice, as has another work dealing with an intimate relationship, Colin McCahon’s The Family (1947) which he first saw at the Manawatu Art Gallery in the mid-1970s.

Harris completed his first major suite of graphic works, The Stations, in 1989. He was aware of McCahon’s 1966 Fourteen Stations of the Cross series (his early works speak directly to McCahon’s), but his primary point of reference was Barnett Newman’s austere cycle of canvases, The Stations of the Cross: Lema Sabachthani (1958–66). Like Newman, Harris uses the religious story of Christ’s final day on earth before his crucifixion as a means of secular political commentary: at the time, his friends and acquaintances were dying of AIDS. We carry each other, and are diminished by each other’s loss, he suggests. Harris’s Stations, and the related paintings, are elegiac and contemplative works of abstraction with a heavy emotional freight. He was thirty-three when he made them – the same age as Jesus at Calvary. Three decades later, he’s about to begin work on a second Stations series.

Ideas make themselves known at different points, and have different rates of gestation. A figure that surfaces in one work might reappear years later. But new ways of working can produce watershed moments and unexpected results. Harris made an important breakthrough following a residency in Paris in 1993, when, increasingly dissatisfied with geometric abstraction, he began experimenting with curvilinear biomorphic shapes. His frustration culminated in an accidental drawing of an elephant, something he later referred to – along with a series of absurd drawings of wigs, moustaches and masks – as “undignified figuration”. Harris is the kind of artist – and indeed person – who goes towards things that make him uncomfortable or uneasy, rather than shying away from them. He referred to the series as “appalling moments”, the elephant as “troubled”, and saw the possibility of personal signification in their unease. The production of these naïve figures, outside the boundaries of conventional artworld taste, was profoundly freeing for him.

At much the same time Harris was experimenting with organic drip forms in two blue-and-white paintings, Territory (1993) and a related study. Like Rorschach inkblots, Harris set up a confusion between figure and field which results in the eye searching the painting for meaningful form: these works anticipate his later interest in exploring negative and positive space. The drips themselves would return later in the decade with the first of the important Swamp works (2000–01), in which vertiginous falls of fluid form themselves into and out of bodies.

In Harris’s practice, each new series of work develops as a response to a new input – perhaps an international residency that brings him into contact with other artists’ works, or an opportunity to work with a new printmaking process – or is otherwise the product of late-night experimentation in the studio, in which a mixture of tiredness and automatic drawing enables an accidental image to emerge. The Drift series of prints (1998) was the immediate precursor to the Swamp works, and is unusual in his practice in that he usually works on both paintings and prints in a given series; there are no Drift paintings. In this series chance marks and impressions afforded by the intaglio print processes suggested imagery to Harris – and a small yellow bird motif, which had appeared the year before when he was working in New York and encountered Martin Kippenberger’s work – flew back into the picture. He came to see it as a representation of himself. In other images, a diminutive figure with a hat takes its place.

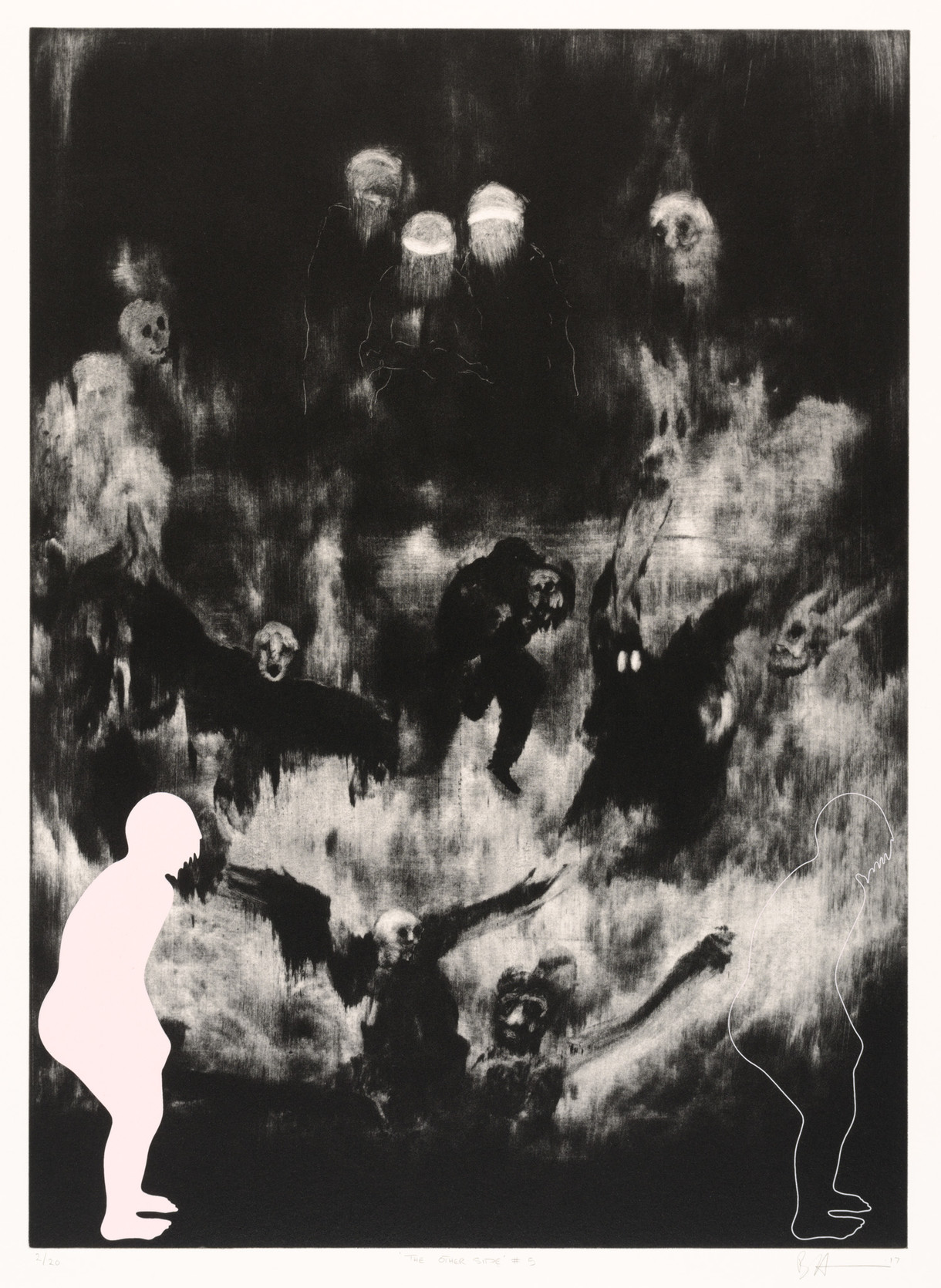

Another radical shift in Harris’s practice came in 2009, while on a three-month residency in Rome, in response to the intense colours of frescoes by Michelangelo, Raphael and Pontormo. He began to create imagery during the process of painting rather, than developing images he had formed through earlier drawings. The new process involved adding and subtracting areas of colour in dabs and washes until form begins to emerge. He’s still making these works – a numbered series of small oils on board – and transfers the imagery at times to larger paintings. The coloured boards also heralded a series of monotypes in which faces and figures well-up from an inky darkness, literally wiped from the surface of the image. Christchurch Art Gallery has The Other Side (2017), a suite of photopolymer gravure prints in which Harris overlaid graphic figures on deeply brushy backgrounds, collapsing together two registers of image-making which are usually kept well apart. His continual experimentation with process and his utter fearlessness in regards to orthodoxies of taste have become hallmarks of his practice.

As much as Harris’s works are the result of a uniquely creative process, they are also themselves about the process of creativity. In his images, form is always in the process of coming into view, and figures are a constant state of becoming. He is never prescriptive about the meaning of his works, although over time he recognises aspects of his own biography in them. In Harris’s compelling and deeply engaging practice, images are formed from the ferment of memory and bodily experience and observation; from the great soup of art history and the exigencies of daily life. Narrative in the images develops out a process of emotional recognition by the artist or his viewer, revealing itself slowly over time spent looking.

The Stations, 1989

“It was 1989, and I had a two-year studio residency at 200 Gertrude Street, a studio and Gallery complex in Fitzroy at the time. I was making prints, drawings and paintings – and sometimes the print came before the painting. The Stations paintings and the prints were exhibited at 13 Verity Street in 1989. But I’d made two prints with John Loane in 1988. One was called Land’s End, a chine-collé, and the other was called Lux – it had a shard on it, very Barnett Newman, and is in the collection of the MCA in Sydney. The title Land’s End: it was touching on mortality, moving into another state. If land ends, what’s beyond it? The more recent work of the same title, that’s about a journey from one state into another. A journey in which you lose your footing.

“The text I used for Stations is the same as the text Barnett Newman used for his Stations; McCahon used a different version for his. I was aware of McCahon’s Stations, of course, and now I look at them there might be a reference to the abstract imagery of McCahon in mine – but it’s Newman’s zip that I was relating to. I’m interested in spirituality; I learned transcendental meditation when I was young. I’m not a religious person, but I do reserve the right to be religious! The other night, we were talking about McCahon’s statement that he wasn’t a religious person, and you said you thought he quite probably was, but perhaps he had more doubt than he had faith. I liked that. I’m going to keep that in mind when I make the next set of Stations.

“Back in 1989, the Stations show sold out before it opened. The Stations of the Cross is a narrative showing a thirty-three-year-old man going from life to death in the same day. I was thirty-three myself at the time, and friends were dying of AIDS around me. The Stations of the Cross is the passage of life before death. Christ goes before Pilate, he’s judged, and then he takes the cross. It’s like: first you become HIV positive. The first fall, the second fall, the third fall. My reading of it psychologically is that each time he falls, his ego is being weakened. So when they finally nail him up, he’s not quite as resistant. Whereas an old person going to death may be more resigned. Well, no one likes the idea of it, me included. Each time Christ stumbles, his ego is crushed a little bit, and yet he has to carry on. So that interested me.

“Number five, Simon Helps to Carry the Cross – well, we all help to carry the burden of each other’s death. The Disrobing related to a Rembrandt etching, The Deposition: he’s being lowered and there’s a beautiful cloth – the NGV owns a glorious facsimile of it. The crucifixion itself came from a memory of driving with my parents to Whanganui as a child: we parked around the back of the Sarjeant Art Gallery. There was an old church hall there; one of the windows had been broken, and one of the white horizontal bars had been snapped off, leaving something that looked like a road sign. It stuck in my mind. That’s what I used – a white cross on black. I flipped it for my Station no.11, a broken black cross on white.”

Appalling Moments, 1995

“I had a studio in Paris for six months, from October 1993 to February or March 1994. Six months was too long. I wanted to get back into making big paintings; I had a reasonable-sized studio in Paris, but I had to get the materials to it, and I had to get the works back home. Four months would have been long enough. I just wanted to get home and get on with it. But there were interesting exhibitions to visit. The Barnes collection was travelling; a big show of Art & Language at the Jeu de Paume; a dealer show of Mike Kelley’s – I started to kick into Kelley, the rubbish drawings, and I was reading as much as I could find on him. But most of the interesting stuff in Paris was historical.

“I was really irritated by the good taste in Paris. It got under my skin. I was making abstract paintings. They were – if not quite polite – tasteful. Then I saw Kelley, who was sticking it to everything! The elephant thing happened after that. First a charcoal drawing, which I sold, so I decided to make a print. I was dealing with these dots, and I was extending these dotted shapes from a painting I’d made, called Caught. I extended the line, which suggested the elephant. I chased it out, but in the end I let it survive. And I identified that as my appalling moment – it was appalling that I should let it enter the abstraction I was doing. I started following that moment. It started to open up faciality for me. It was the moment that created the possibility for anything to happen. Once I allowed that in, it just opened things up.”

Drift and After Drift, 1998

“Apart from the bird, these images were formed in the making of the prints. I had the drawings I’d made in New York with me, and that bird that first appeared in On Becoming (Yellow no.3) (1996) then becomes me on this journey – a symbol of the artist. This Drift series is a precursor of Swamp and To the Forest.”

All quotes taken from an interview with Brent Harris by Lara Strongman, Melbourne, 26 August 2018.