John Simpson

A Generous Gift

Early in 2017, Professor John Simpson, the former head of the School of Fine Arts at the University of Canterbury, approached the Gallery’s then director, Jenny Harper, with a proposition: he had been considering the future of the art collection he had accumulated over the past six decades, and wished to know whether the Gallery would be interested in selecting a group of works for a gift. My colleague Ken Hall and I visited John one afternoon in March. It quickly became apparent to us that the collection was significant and that the offer was particularly generous. Interestingly, we discovered that the works variously represented John’s own artistic interests and his national and international artworld connections. As such, they told a story of art and art history that usefully expanded the local account.

John Simpson arrived in New Zealand in 1958, appointed as a senior lecturer in design at the University of Canterbury. A notable silversmith (one of only six invited to make work for the Festival of Britain in 1950), he’d been lecturing at the College of Industrial Design in Newcastle upon Tyne, where he had a hand in developing one of the first courses in Britain for industrial design. He’d been trained in traditional silversmithing techniques in order to make prototypes for objects designed for mass production. Interviewed by a selection board at the University of London that included the pre-eminent art critic Herbert Read, he was appointed to the position and sailed to Christchurch first class with his wife Ming, on board the S.S. Gothic.

He was more than a little horrified when he arrived at the School of Fine Arts, then housed in the re-purposed Okeover buildings out at the Ilam campus. (Famously, the art school was one of the first departments to move from town to Ilam, and one of the last to get its own building.) In fact, he described the buildings and facilities as “woefully inadequate”, and spent the first three months in the job over the summer making tools so that he could actually teach silversmithing the following academic year. The art school itself, he commented, was typical of a British art school of thirty years earlier, still teaching under the influence of the Victorian South Kensington system. He changed that as soon as he could, instigating group projects to “promote a sense of family” among the students.

When the head of the school, Colin Lovell-Smith, died unexpectedly, Simpson applied for the job. He was in two minds about his application; before leaving Britain, he had been promised a lectureship at the prestigious, progressive Central School of Art in London in three years’ time, and had intended to stay in New Zealand only that long. He was also concerned that his wife, who was an identical twin and close to her sister, would be missing family in England. In the end Ming Simpson encouraged him to apply for the role. The chances of him being appointed as the chair of an English art school were low, she said, and this represented a significant opportunity for him. Three candidates were brought out from Europe to be interviewed for the position. “It came as a very big surprise when they appointed me,” he said.

As head of school and the first professor of fine arts at Canterbury from 1961 until his retirement in 1990, Simpson did much to modernise the art school and to raise its profile and status among other university departments. He was a fierce advocate for the student body, and employed many high-profile practising artists as lecturers, including Don Peebles and Doris Lusk. He arranged for the teaching staff to have a day off a week to work on their own studio practices, and forged links with other university departments, in particular psychology, which was developing experiments into visual perception.

Privately, he collected works by New Zealand artists he admired and wished to support, including Lusk, Vivian Lynn and his colleague Maurice Askew, who taught film at the art school. He has an ongoing interest in historical British printmaking, acquiring significant works by Hogarth and Rowlandson over the years. When we visited John, he encouraged Ken and me to make a list of all the works we thought could find a useful home in the city’s collection. We followed his instructions, and were astounded – and very moved – to find that John and his family had approved the gift of everything on the list, including John’s own early designs in silver and two significant eighteenth-century silver pieces, among them the only known work by Hester Bateman in New Zealand. John was keen that a piece of this calibre remain in Christchurch for later generations to be able to see at first hand. The collection was given to Christchurch Art Gallery by the Simpson family in memory of their late wife and mother Ming Simpson, who passed away in 2012. We’ll be using these works often in our future exhibitions.

Hester Bateman, Silver Coffee Pot, 1779

It’s a remarkable coffee pot, in such perfect condition. I’ve got an idea it’s been put away in a drawer for donkey’s years, and hardly ever used, because the engraving on it is as sharp as if it were done yesterday. I came across it in North Canterbury, when I was doing assessments for insurance. I said I would need to get corroboration that it was genuine, because the mark was slightly effaced. I sent high-resolution photos of the mark to the V&A, to a friend who was then keeper of metals there. He was prepared to write a letter of authentication that it was a genuine mark. I was toying for a while recently with the idea of selling it through Sotheby’s in New York. But in the end I thought it would be nice to have something of that quality in a public collection in Christchurch.

Vivian Lynn, Clouded Bay, 1965

This is a lovely landscape, a beautiful painting. A mixture of oil and wax. It’s a luscious painting, almost liquid, with a dry-brush skating across the surface. The landscape is Cloudy Bay. It hung in my bedroom for years, and I never got tired of it. Every morning I’d wake up and see something different in it. I purchased it from one of the Hay’s Prizes. At that time I was writing for the Press, and I featured it in my review, and then backed my opinion by buying it! Vivian was a marvellous person, a stalwart, defending the rights of women.

John Simpson, Teapot, 1950

I made the teapot for the Festival of Britain in 1950. I don’t quite know how it happened, but I became known for making teapots. I had a series of commissions, and then I was invited by the Tea Council to advise them on the design of teapots. They had a building in Lower Regent Street in London… their job was to make sure people had reliable information about tea. A lot of myths had grown up about tea in Britain. For example, people had been advised never to stir tea. In the eighteenth century it was believed that a large part of the enjoyment of tea was due to the supernatant oils, which gave it its fragrance. Stirring would have drowned these oils and the fragrance would be lost. When something new came out, the Tea Council would invite me to review it, from a design perspective. So I became almost by accident a person who could be consulted about teapots.

I was invited to make a teapot for the Festival of Britain on the Southbank. And because it was going to be seen by literally hundreds of thousands of visitors, I engraved my name on top of the teapot. Free advertising!

At that time I did quite a lot of research into pouring. And I eventually hit upon a shape for a spout where it was impossible to get the liquid on to the wrong side of the pot. It was a matter of trial and error, gradually approaching a form that was 100%. After that, I got more orders than I could handle. If you’re really good, you can make a pot in about ten days. You can’t make one any quicker

John Simpson, Coffee Pot, 1951

I made the coffee pot a year later, in 1951. I’d like to think it represents a slight advance – me being another year older, and exposed to more influence and development. It’s just a little bit better in its design. It was exhibited at the V&A at one stage, on temporary loan for a year.

The Latin inscription translates roughly as: After a day’s exertion, it’s sweet to sit in front of the hearth, enjoying the warmth of the fire.

I didn’t hallmark the either the coffee pot or the teapot because I never intended to sell them. You can’t sell silver in Britain without a hallmark. It’s an offence. I knew they were good, and I wanted to keep them in the family.

Thomas Rowlandson, Bachelor’s Fare, or Bread, Cheese, and Kisses, 1813

The entire drawing is done with brush only using watercolour pigments and it is without question a tour de force of brush technique. It is said he got

an engraver to run off a large number of prints. Of course the prints were a right-to-left inversion. The prints sold like hotcakes because people believed it featured the Duke of Kent, who was well known for disappearing from State

occasions and ending up in the kitchens, flirting with the kitchen maids. The print was taken up by less than scrupulous engravers, who borrowed the image and sold it under their own names. This led to a large number of such prints in circulation. But the watercolour brush drawing is the genesis of them all.

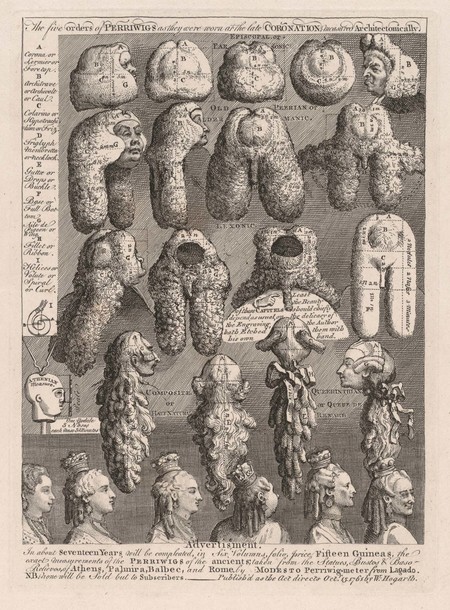

William Hogarth, The Five Orders of Periwigs, 1761

I acquired three particularly interesting prints by Hogarth from an antiquarian print and booksellers in Gower Street in London. They came from the estate of Mary Hogarth – Hogarth’s wife. The Five Orders of Periwigs is a lovely skit on the pageantry of the legal system, the various wigs worn by different grades of judges – all done very tongue-in-cheek, lampooning the hierarchy. It would have been perfect to include in the Gallery’s recent Bad Hair Day exhibition!

Doris Lusk, Church Road, Kaitaia, 1967

Doris was a colleague of mine – and a wonderful person. I often purchased work from her exhibitions. This is a very loose and expressionistic painting. It was auctioned at the CSA – as it was in those days – and contested by Miles Warren and myself, bidding against each other. I stuck it out, and won!