Wurms Rule

The work of Jess Johnson

As I write this I’m listening to Grimes. Jess Johnson likes Grimes. It’s the kind of music you might hear playing in her studio as she sits creating her complex drawings of alternate realities, line by meticulous line. A quiet achiever with numerous accomplishments under her belt, Johnson’s work ends up in all sorts of places – from the walls of Australia and New Zealand’s major institutions to the backs of some of pop culture’s coolest figures. Back in 2016 she collaborated with Australian fashion designers Romance Was Born on a range of clothes, some of which ended up being worn by Grimes herself. Not that you’d necessarily hear about this from Johnson, who is remarkably modest.

As I write this I’m listening to Grimes. Jess Johnson likes Grimes. It’s the kind of music you might hear playing in her studio as she sits creating her complex drawings of alternate realities, line by meticulous line. A quiet achiever with numerous accomplishments under her belt, Johnson’s work ends up in all sorts of places – from the walls of Australia and New Zealand’s major institutions to the backs of some of pop culture’s coolest figures. Back in 2016 she collaborated with Australian fashion designers Romance Was Born on a range of clothes, some of which ended up being worn by Grimes herself. Not that you’d necessarily hear about this from Johnson, who is remarkably modest.

Hers is a largely solitary practice; locked away in her tiny New York studio she concentrates on creating her own world (typically realised through drawings and increasingly the moving image). Perhaps this is the legacy of a quiet upbringing in pre-internet Tauranga, where Johnson immersed herself in science fiction, devouring books by Octavia E. Butler, Ursula K. Le Guin, Ray Bradbury and Frank Herbert. To this day, some of her favourite images are sci-fi book covers from the 1960s and 1970s. Johnson uses sci-fi as a convenient umbrella term for expressing interests that aren’t easily articulated in language. But the alternate realities that proliferate in the genre are key. Johnson’s relationship with reality is complex, she sees it as fluid, rather than fixed; “Probably like a lot of kids I had this idea that there was more to the world than what was being revealed to me, and if only I discovered the right access points a door would open in the air and I would enter the world of the ‘really real’. The place beyond reality, where reality is made.”1 These teenage preoccupations grew in Johnson’s art student days at Ilam in Christchurch where she painted “hyperreal futuristic cityscapes populated with indeterminate looking cyborgs. They were bald back then too. Lots of squares and flat planes connected with snaky machinery tubes.”2 Even at these early stages she was assembling the building blocks for her universe.

Twelve years in Melbourne followed, where from 2008 until 2011 Johnson also co-founded and programmed the popular inner-city project space, Hell Gallery, with her then-partner and fellow artist Jordan Marani. Constructed with detritus from institutions including the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art where the couple worked as art installers, Hell was situated quite literally on the ground floor of Johnson and Marani’s Richmond home. The unconventional gallery spaces (including the tiny “Hell Toupee”, which had to be entered on all fours) were complemented by live bands and barbeques, evidence of Johnson’s belief that providing a relaxed and friendly context for engaging with art could playfully upstage the antiseptic, “please do not touch” environment of the white cube gallery. Hell’s intimate scale and casual approach permitted artists to take risks, develop new work and test it out on eager audiences.

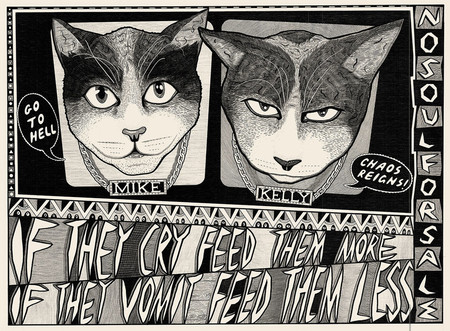

Jess Johnson If They Cry Feed Them More 2010. Pen, fibre-tipped markers on paper

An extension of her own practice, Hell was a time of experimentation for Johnson too. Of particular significance were the hand-drawn posters she photocopied and distributed around town for each exhibition, which allowed her drawing style to develop with absolute freedom. She channelled her love of comics, sci-fi, horror, collage and the DIY music scene into them; “I wasn’t editing myself or being concerned about making serious, important artwork. By doing these posters I reconnected with this really genuine, unfiltered enjoyment of drawing, which was really close to how I’d felt about drawing as a teenager before I went to art school and had it drummed out of me.”3 As well as being deeply personal, (take 2010’s If They Cry Feed Them More for example, featuring Johnson’s cats Mike and Kelly in pride of place, complete with feeding instructions and quotes from Lars von Trier’s film Antichrist) these posters also reveal Johnson’s interests in pattern-making, the use of text as a compositional element and popular culture.

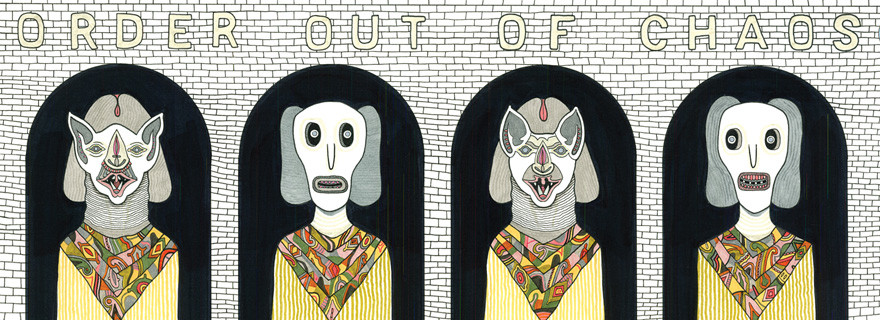

With the close of Hell in 2011, Johnson began to develop her drawing practice intensively, also stopping work as an art installer to concentrate on her own work full-time. Accordingly, her world continued to reveal itself in more intricate ways. Her drawings matured to include a number of key recurring features: towering architecture, complex patterns and a growing community of cryptic symbols including genderless automatons and entanglements of writhing worms. Worms have long occupied Johnson’s thoughts (she recently recovered old school projects containing elaborate borders composed of worms, created aged eleven). A respite for both creator and viewer, Johnson’s “wurms” break the rigid geometries of her austere landscapes and provide an organic entry point into the drawings. She says; “I’ve always considered the wurms to be the brain and compulsion system of the world. The geometry and pattern is kind of mindless. It’s like the world needed a battery (or a brain?) and that’s what the wurms represent. They represent the physical manifestation of knowledge or data.”4

Jess Johnson and Simon Ward Terminus 2018. 5 x Virtual Reality experiences, floor map, structures, drawings, 4 channel projection

Johnson often creates elaborate environments (including elements like patterned wallpaper and tessellated flooring that reflect the patterns in her work) to act as entry points into her drawings. However, her relationship to these environments has changed dramatically with her move into virtual reality, in which drawings are converted into immersive 360° environments utilising Oculus Rift technology, realised through her collaboration with video maker Simon Ward. Reflecting on her earlier installations, Johnson observed: “I think I was always reaching for something, like I was trying to create a portal into this other world and was using these really ineffective tools of sticks and paint to do so.”5 VR made her traditional installations “instantly redundant, but opened up this incredible world of possibility. It was the most exciting thing that has happened to me as an artist.”6

Johnson’s moving image work has expanded the realms of her world significantly and Ward (along with sound designer Andrew Clark and animator Kenny Smith) is instrumental in bringing these visions to life. In contrast to Johnson’s drawing practice, her moving image works are deeply collaborative. Ward has access to her entire archive, transforming and expanding her drawings into a three-dimensional world using the games program Unity; “She sets up the look and I inject more of the time-based aspects – how those designs work in time.”7

Johnson and Ward met through friends and in 2014 created their first moving image work, the hypnotic Mnemonic Pulse – a first-person journey that simulates the experience of walking through one of Johnson’s drawings. It was during the development of this work that the pair first discussed utilising VR, which resulted in Ixian Gate (2015) and more recently in the suite of five new works included in Terminus, their solo exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra earlier this year.

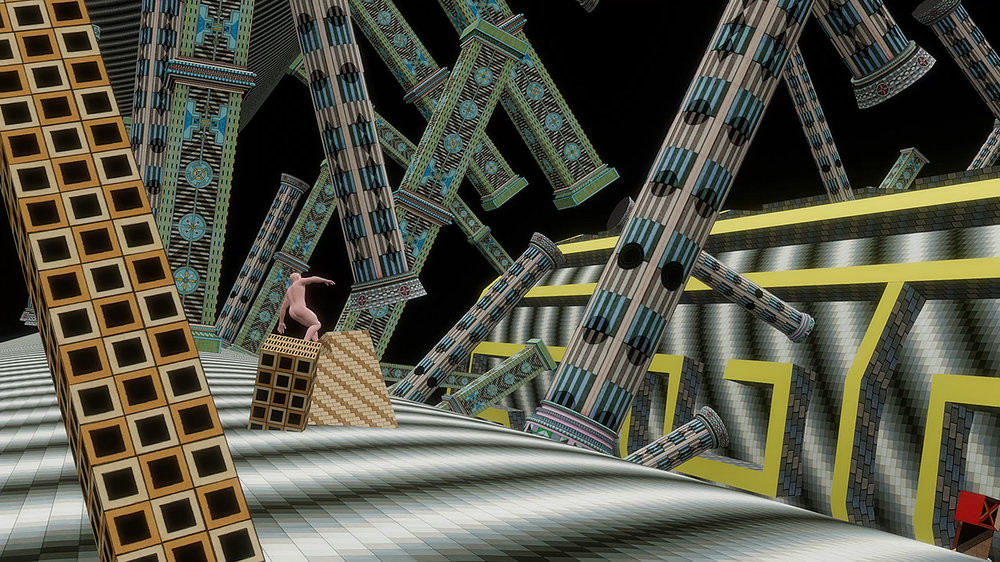

Like Johnson’s drawings, the duo’s VR works are not easily articulated in language. Rather, they are profoundly insular experiences that are unsettlingly like mainlining directly into Johnson’s brain. This effect is not lost on the artist, who is delighted that her visions are seared onto the minds of others. The journey through these spaces is tightly controlled by the universe’s creators, as we are propelled through virtual space magic-carpet-style by unseen forces. Flitting between moments of profound beauty and terror, these journeys take you to the edge (quite literally, when you find yourself teetering on the very brink of a world that is rapidly rotating beneath your feet) but never beyond it. When traversing through the soaring architecture of Scumm Engine (2018) I was so overwhelmed by the enormity and beauty of the world that I was moved to tears, succumbing completely to the experience as the real world slipped away. Johnson is often asked whether viewers will one day have the autonomy to forge their own way through this virtual world but the answer is a resolute no – she rules this universe; you encounter it on her terms alone.

Jess Johnson and Simon Ward Scumm Engine (VR still) 2018. Virtual Reality animation with audio, 5:35. Developer: Kenny Smith; sound: Andrew Clarke

Johnson’s world, which continues to grow in complexity and ambition, is a constant. The context in which it is created however is not. Despite now living permanently in New York, Johnson manages to get home to New Zealand often, bunkering down with her parents in Whangarei Heads a couple of times a year. For Johnson, moving between the two reflects her constant state of imbalance or discontent. She says “The discontent is like an engine or a generator... swinging between the two is the state that is actually productive.” There’s a kinship here with how her practice shifts between the physical and the virtual. She has to keep moving. As Johnson observes; “I’ve always liked that analogy of how sharks have to always keep swimming facing the current. And if they stop swimming they’ll drown.”8