Zero Degrees of Separation

The New Zealand art world is an intimate place but my connection to Jenny Harper runs deeper than the usual bonds of a small community. Admitting this is a necessary disclaimer. I’m not an objective commentator; Jenny is family, literally. And professionally, I owe her plenty. What follows are some personal recollections about the Jenny I know through the associations we share, on the occasion of her imminent departure from the Christchurch Art Gallery, where she has been director since October 2006, making this the longest role in her distinguished career.

'Jenny has the unique ability to throw herself into a new situation and to make it her total focus, then to rally her troops to realise her vision.'

My mother’s father, John Loughnan, was the grandson of Robert and Frances (née Barnes) Loughnan, who settled in Christchurch in 1868, brought up nine children, and quickly became doyens within the nascent city’s social hierarchy. John’s father, Frank, was one of their offspring; and Agnes, his sister, another. Agnes married George Harper, a son of the first Bishop of Christchurch and she is Jenny’s great-grandmother. According to an online ‘cousin calculator’, that makes us third cousins. Having grown up in England with parents who gravitated towards our ‘British’ relatives, I had little knowledge of my New Zealand forebears, until I was a student at the University of Canterbury in the mid 1970s and my mother suggested I connect with her family still based there. I made only one contact, with Katrine Brown (a second cousin once removed) and her American husband, who kindly invited me for a meal one Sunday evening. I didn’t know it then, but Katrine (who had attended my parents’ wedding in England in 1950) was Jenny’s favourite older relation, someone who took her to art openings and studios in Christchurch, sowing the seeds of her interest in art history in the wake of the horrible accident that left her permanently scarred.

All this came out years later, I’m not even sure why or how, but certainly well after I had started working with Jenny in 1992. Since then, our family ties have become something of an in-joke, a reminder of just how close people can be on these islands we share. But, these ties have also helped me understand those attributes Jenny inherited: old-fashioned manners, social ease, pedantry about ‘good’ grammar, fearlessness in facing challenges, a wicked laugh. I know what it means to say she’s very ‘Christchurch’. That said, she’s not one to play the silver spoon. Instead, she is fiercely independent, driven even, and totally committed to whatever job she is in. As she says, she and her sisters were never going to inherit the farm, so they had to make it on their own. And Jenny’s done that in spades.

The other joke Jenny loves to tease me about is the fact that she has had the dubious honour of appointing me to three of my four ‘proper’ jobs. As final director of the National Art Gallery, Jenny was on the selection panel that appointed me to be curator of contemporary art, a post I took up in January 1992. Several in the art world thought this a poisoned chalice, compromised as it was going to be by the forthcoming merger foisted on it that saw it subsumed into the newly-minted Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, a ‘super-museum’ in which art had to jostle for space and resources alongside other ‘departments’.

In fact, at first, the job was better than I had been led to anticipate. I found Jenny to be an enabler, supporting my plans for shows and encouraging acquisitions, including sending me to Canberra to meet Imants Tillers to seal a deal she had initiated to acquire his multipart masterpiece, Diaspora (1992). Looking back, I see this as an early indication of her ambition to bring major works by international artists into local collections – think Bridget Riley, Martin Creed and Ron Mueck. By then, Jenny had been a staff member for six years, joining as curator of international art in 1986 – after working in Australia as assistant curator of international prints at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra (1983) and curator of European art at Queensland Art Gallery – and assuming the role of director on Luit Bieringa’s departure in 1990. She was enough of a believer in the new museum to not only make the transition but to help steer it into existence.

But there was a tipping point when, under Cheryll Sotheran’s leadership, the Museum set its course to become ‘Te Papa’ and staff were strong-armed to focus exclusively on the opening of the new waterfront building and on what the leadership team called ‘Day One’. Jenny elegantly stepped out of her role as director of ‘museum projects’ to become the inaugural head of Art History at Victoria University at the end of 1994. Within six months I had joined her as a lecturer, a role Jenny offered me after the panel’s first choice turned them down. The next five years were exhilarating. Jenny has the unique ability to throw herself into a new situation and to make it her total focus, then to rally her troops to realise her vision. She turned a blind-eye to the cruel remarks from academic colleagues that she was brought in by the university because of her ‘managerial’ credentials, a sign of intellectual decline (according to them) in an era of economic rationalism. If managerial meant using the university’s strategic plan to our advantage, fostering key alliances with senior leaders, understanding the value of a ‘product’ that had coherence and focus, then creating opportunities to extend beyond ‘core business’ and position Victoria as the leading art-history programme in New Zealand, then I don’t think anyone should complain.

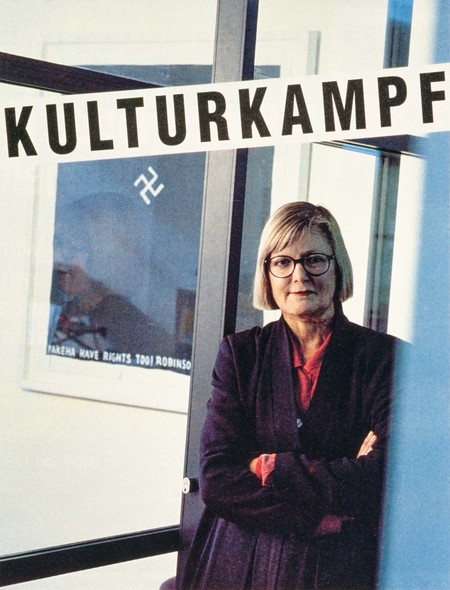

Jenny Harper, as pictured in the New Zealand Listener (5 Sep 1998; v.165 n.3043:p.38-40) with Peter Robinson’s Pakeha have rights too! (1996). This work hung in Jenny’s office at Victoria University, where she staunchly defended its controversial iconography in face of robust criticism from several students and staff who disapproved of the work’s prominent swastika and seemingly racist sentiments. (See Tessa Laird: http://www.physicsroom.org.nz/archive/2cents/hasty.htm)

In those five short years Jenny made some clever appointments (Peter Brunt and then Roger Blackley joined the programme after me) to encourage a focus on art history in our region. She galvanised us to develop a coherent programme of courses from first year through to Honours, and we began to offer masters, then PhDs. Jenny was not a scholar in any deep sense, but she brought her personal experiences to bear in her teaching to grant the subject relevance and loved to play against type by donning silly glasses and reading a Hugo Ball poem at the start of her lecture on Dada in her Modernism paper. She also kept us well-connected to the wider scene, facilitating visits by leading scholars (Michael-Ann Holly and her husband Keith Moxey, David Carrier, John C. Welchman, John O’Brian, and René Block were all memorably hosted, sometimes with catered dinners in our tiny departmental library), and keeping in touch with the museum world through consultancy and curatorial work that extended the department’s reach and secured Jenny’s continued visibility.1

Her other major achievement at Victoria was to realise the Adam Art Gallery, the institution I now direct, in a position I applied for and was appointed to by Jenny (amongst others), who by then had moved up the administrative chain to her final position at Victoria: assistant vice-chancellor (academic). It was perhaps one of her last responsibilities before setting off to direct Christchurch Art Gallery in October that year. I had the privilege of working closely with Jenny on the Adam and saw her powers of persuasion at work at every level. Its existence can be put down to an unbeatable combination of vision, determination, good timing and generosity. Jenny was certainly responsible for the first two; the University’s centenary celebrations provided a focus for fundraising and account for the third, and the beneficence of Denis and Verna Adam in offering a million-dollar challenge donation was the final vital ingredient. A steering committee oversaw the project, but really, I think the Adam was Jenny’s achievement.2 She secured the University’s support, brought donors on board, chose the architect and saw the building through to opening in September 1999, supporting my idea for the inaugural exhibition: a suite of mini-shows each revolving around a key work in Victoria’s art collection, before appointing the first director (Zara Stanhope) and playing her part in the institution’s nascent governance structure.

Yet, probably what is better remembered than this extraordinary achievement (realised for a little over $2million), was the notorious sale of McCahon’s Storm Warning (1981) – a gift to the university art collection from the artist – to cover a small shortfall in the budget, with the remainder invested for the collection’s future development. Despite the collective decision – made before the collection was protected by any formal policies and with the approval of McCahon’s Wellington dealer, Peter McLeavey; Tim Beaglehole, the collection’s de facto guardian; and senior University leaders including the vice-chancellor – Jenny wore the controversy, facing the media, and doing her best to explain the decision. She took the full brunt of the collective outrage this decision caused on campus and its wider ripples, and never passed the buck. I’m not sure how I would have dealt with such heat, but she weathered it, and moved on.

I admire that tough streak, and have seen it in action before and since. It certainly stood her in good stead in Christchurch after the fateful earthquakes of September 2010 and February 2011. Jenny has always been success oriented, so to see her institution stopped in its tracks for five years must have been heart-breaking. I admire how she did not give up, how she (again) galvanised her team, made the Gallery a cultural rallying point through a programme of offsite, online, and in-print projects that kept artists and audiences engaged, fought for resources to see the Gallery strengthened and reopened, and led a campaign to secure funds for a handful of legacy acquisitions. It’s what I’ve come to expect and shall always respect about her way of working. After twelve years at the helm, I think she deserves a rest. I don’t imagine this will see her bowing out, nor even necessarily slowing down, especially when the cultural values she upholds need to be reinforced and defended; that task is in her bones.

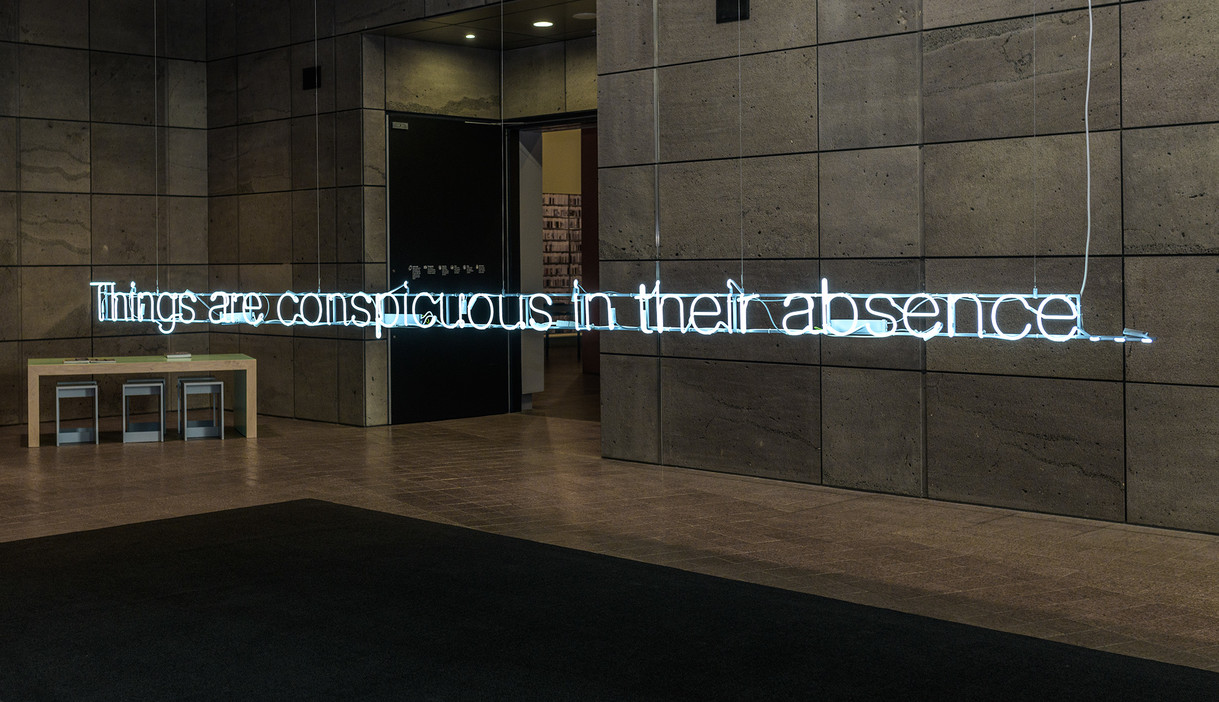

Martin Creed Work No. 2314 2015. Neon. Commissioned by the Christchurch Art Gallery Foundation, gift of Neil Graham (Grumps) 2015