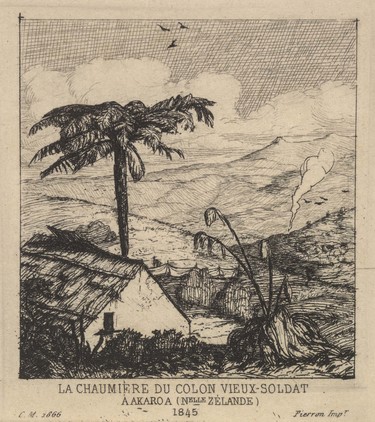

Charles Meryon La Chaumière du Colon Vieux-Soldat Akaroa 1845 1866. Etching. Collection of Canterbury Museum

Charles Meryon: Etcher of Banks Peninsula

French explorers, natural historians, whalers and Catholic missionaries were increasingly present in the south-west Pacific from the mid-eighteenth century, but there was also a political thread in this activity. During the 1820s some in France saw New Zealand as a potential penal colony, and the project that saw a handful of French colonists settle on Banks Peninsula in 1840 made an official French presence in the region even more appropriate. This took the form of a French naval base, the ‘New Zealand station’, established at Akaroa in 1840.

The execution of France’s complex political-commercial-religious policy in New Zealand and its region depended on a succession of ships, including the Rhin, commanded by Captain Auguste Bérard. It left France in August 1842 and reached Akaroa in February 1843. During the time it was based here the Rhin made several voyages around New Zealand, visiting Port Nicholson, Auckland and the Bay of Islands, and, further afield, New South Wales, Chile, the Marquesas, Tahiti and several other groups in Polynesia, Micronesia and Melanesia, before returning to France in the second half of 1846.

Charles Meryon (1821–1868), the Paris-born son of an English doctor and a French dancer, was among those who sailed on the Rhin. As a teenager he had dreamed of entering the navy, and a spirit of adventure and a desire for foreign travel coloured his ambitions. He had already received training in drawing and watercolour before he left France as a naval cadet, 1st class. He was promoted to the rank of ensign in mid-July 1844.

So he was an inadvertent participant in, and observer of, the process of European colonial expansion. The sophistication of Hobart and Sydney (and the surprising progress made by the settlers at Auckland and Port Nicholson in so short a time) demonstrated one aspect of this, and he also observed interactions between Europeans and indigenous communities. In another register, he could see international politics in action even in Akaroa, as rival authorities negotiated the resolution of French land claims.

Meryon returned to France with a store of memories and drawings which he exploited after resigning from the navy to follow a career in the fine arts. His earliest projects belonged to the conventions of history painting, but it was after he turned to etching and took Paris itself as his principal subject that his originality as an artist really began to flower. Moreover, his perception of Paris, and his expression of that perception, were influenced by his experiences in the Pacific, and in the 1860s he returned to that region for new subject matter, which he expressed most accessibly in his Pacific Set.

Meryon’s images of the Pacific fall into three groups – the drawings he made during the voyage of the Rhin; his recollections of the Pacific incorporated in a group of curious ‘hybrid’ etchings, some with predominantly Parisian content; and finally the prints illustrating subjects from Oceania. Banks Peninsula has its place in all three.

In the first group, the drawings he made in and near Akaroa can be set alongside those made there by other French visitors – Louis Le Breton in April 1840, an unidentified draughtsman later in the same year, and Jean-Jacques Jagerschmidt from November 1841 to January 1842. Some of their images are footnotes to the history of French exploration in the Pacific and others document the beginnings of French colonial expansion in the southern hemisphere.

Many of Meryon’s prints of the ancient heart of Paris were antiquarian undertakings, but Paris was more than memories of a glorious past: in the present it was also home to crime, disease and human misery, as exemplified in his 1854 study of a sordid medieval street, the Rue des Mauvais Garçons (The Street of the Bad Boys). That etching has explanatory verses integrated into the image.

What mortal lived in this dark dwelling? Who hid there in the night and in the shadow? Was it poor, silent Virtue? Crime you will say – or some evil soul perhaps... Oh!, in faith I do not know; if you wish to know, oh curious one, go and see. There is still time.

The second group of Meryon’s Pacific etchings, his hybrid images, challenge the viewer by their puzzling juxtaposition of Paris buildings or allusions to contemporary figures and events – the unhappy ‘here and now’ in which Meryon was trapped – with images taken from his experiences in the Pacific – the ideal ‘there and then’.

The most celebrated of these are Collège Henri IV (ou Lycée Napoléon) (Henry IV College, or Napoleon Lycée) of 1863–4, in which a Pacific seascape complete with canoes washes over part of the Left Bank, and Le Ministère de la Marine (The Admiralty) of 1865–6, in which diverse figures and objects, including a Māori canoe, fly through the sky. Neither of those etchings makes any specific allusion to Banks Peninsula, but relevant glimpses can be found elsewhere. In the elaborate frame for a portrait made in 1862 – Projet d’Encadrement, pour le portrait d’Armand Guéraud (Project for a Frame, for the Portrait of Armand Guéraud) – the blockhouse built in 1845 to protect the Akaroa settlers from a possible Māori attack, can be recognised in the upper-right corner; and a rebus, or word puzzle, known as the Morny Rebus (1866), incorporates views of a pā at Port Levy and what is perhaps a cliff at the entrance to Akaroa harbour.

Charles Meryon Le Malingre Cryptogame, 1845 1860. Etching. Collection of Canterbury Museum

Finally, there are five literal recollections of Akaroa itself etched from 1860 to 1866. In these prints Meryon expressed a personal yearning more clearly than he had in those hybrid images. He once told a friend that he hoped to return to the Pacific and end his days here, and even suggested that his elderly father, living in retirement in London, and his half-sister Eugenia, should emigrate and settle on Stewart Island!

The most curious of these is Le Malingre Cryptogame (The sickly cryptogamia) of 1860. It falls far short of idyllic, exotic dreams, and the transformation of a small natural history study into a carefully executed etching appears intrinsically eccentric, but Meryon himself made clear that he saw it as an exemplary object. One day while out walking, he saw ‘this poor little fungus’ which ‘seemed to me to personify that misfortune, that bizarre twist of fate which presides over incomplete, sickly creations.’1 The logic which gave it a place in his etchings of Pacific subjects is perhaps an autobiographical one, and the deformed, unfortunate fungus could perhaps be interpreted as a wry self-portrait.

The 1860 print titled Greniers indigènes et habitations (Native storehouses and dwellings) appears at first sight to be an unproblematic record of a peaceful, exotic scene, and if the gestures of the Māori are interpreted as welcoming, this is an illustration of friendly intercultural contact. However, reading those gestures as subservient introduces undertones of colonial dominance into the picture.

The etching begun in 1863 but completed only in 1866, given a wordy title that can be conveniently abbreviated to Pointe dite des Charbonniers, à Akaroa (Charcoal Burners’ Point at Akaroa), is perhaps the masterpiece of the Pacific set. The broad, still harbour replete with a few small craft, the fishermen and incongruous strollers enlivening the subject, the distant hills and a summer’s sky with dramatic but non-threatening clouds, all add up to an image of peace and calm. It provides a powerful contrast to the narrow, oppressive Paris streets with their hidden dangers of disease and crime that Meryon was etching in the same period.

A general view of the village etched in 1864 was called the État de la petite colonie française à Akaroa, vers 1845 (State of the little French colony at Akaroa, about 1845). Although the mood of this image is one of quiet industry in a peaceful landscape, the title itself, and the inclusion of the blockhouse, give the print a subtle political subtext. Meryon singled it out in a letter written in December 1866 as being, despite its modest size, of particular importance ‘at the present time […] when the country needs suitable and healthy colonies’.

In the last of this group, La Chaumière du colon vieux-soldat à Akaroa, 1845 (Cottage of the ex-soldier settler at Akaroa, 1845) made in 1866, Meryon continues to document life in the raw settlement as he knew it in the 1840s, but by narrowing his focus to concentrate on one man he emphasises the personal dimension of the life that may be led by humble settlers, in a cottage such as this, beneath a tree fern, or surrogate palm tree. ‘It represents’, he wrote to the Minister of Fine Arts to whom he sent an impression in May 1866, ‘a sanctuary of rest and well-being, in conformity with the wishes most of us have for our old age, after an honourable and active life.’ Added resonance is given to this plate by the identification of the ‘former soldier’ as François Rousselot (1801–1862), who had fought at Waterloo thirty years before and whose new life as a settler was far removed in space, time and emotional climate from the dramas of his youth.

But as well as being the embodiment of a personal message this group of prints was also an oblique ‘pamphlet’ in support of colonial expansion and emigration from Europe, with colonies in general and the Pacific in particular, offering possible solutions to some social problems in France. Among Meryon’s friends, associates and supporters in the 1850s and 1860s was Armand Rochoux, an art dealer, print publisher and author, whose 1848 book Organisation du travail. Solution présente. combines social comment and economic theories. In it Rochoux expressed views on immigration into France, but also suggested that emigration could be a cure for unemployment and a way to reduce domestic social pressures. This book foreshadows some ideas Meryon explored in the 1860s.

Charles Meryon Nouvelle-Zélande, Greniers Indigènes et Habitations à Akaroa (Presqu’île de Banks, 1845) 1860. Etching. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1972

Many of his Parisian images sought to express a moral message, and so too did his Pacific etchings. On 7 October 1866 Meryon made two attempts to draft an explanatory text to put this point across. In the more developed version, he claimed that this series had artistic and moral value and that it was particularly relevant to the social and political aspect of exploration and colonisation.

Those cryptic remarks had already been clarified in May 1866, in a letter written to the Minister of the Imperial Household and the Fine Arts: the development of colonies could counteract the spread of vice in large urban centres and provide, in cottages such as the one represented in the Chaumière print, an ‘asylum of rest and well-being’.

Indeed, Meryon saw his Pacific prints as playing an almost polemical role and himself as something of a prophet. Early in 1865 he had written to the Minister of the Imperial Household and of Fine Arts to explain his motivation.

[...] placed in the impossibility, despite my perseverance, my good will, my vehement wish to serve what is for me the obvious good cause; to plead for it, with truth, by exact and conscientious images, in this art which I had adopted, in which I had faith; in which I saw a salutary support against the ills of this world; I would propose to express once again, with God’s help, within the limits of my strength, this sincere theory which I have developed concerning the laws according to which our existence on this earth must be rationally conducted.FTN-2

Thus we can see that personal concerns were joined in Meryon’s mind with a duty to serve humankind, and from September 1861 to August 1866 he made numerous attempts to find support for the publication of his prints and the ideas they embodied. However, neither the Naval and Colonial Ministry, nor a former fellow-officer who was now an admiral, nor the Minister of the Imperial Household and Fine Arts, nor a Paris print seller he approached in 1866, was willing or able to help him.

As an active proponent of colonial expansion Meryon’s was a lost voice, but as an idealist for whom the South Pacific had revealed an alternative to the social hell of a great European city, his vision was distinctive and original.