Barbara Brooke: The Woman Behind Ascent

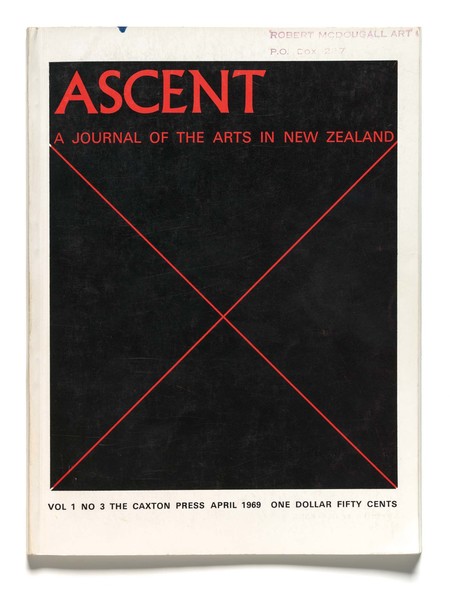

Ascent: A Journal of the Arts in New Zealand, vol.1, no.3, April 1969, The Caxton Press, Christchurch

The 1960s brought television, youth culture, jet aircraft and The Beatles to New Zealand. It also saw the emergence of the professional contemporary artist. Dealer galleries were on the rise across the country, devoted to the promotion and sale of contemporary artists’ work, particularly through solo shows, and with them came the possibility of an acknowledged career with the objective of full-time practice. Artists were producing work with a general sense of confidence and this lively art community needed to be documented.

Ascent: A Journal of the Arts in New Zealand, vol.1, no.3, April 1969, The Caxton Press, Christchurch

In 1965 Christchurch’s Caxton Press was approached by the Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council (now Creative New Zealand), who asserted that New Zealand needed an arts journal.1 A quarterly publication was deemed ideal – the kind of document found on coffee-tables in private lounges and offices. The periodical that would eventually become Ascent: A Journal of the Visual Arts in New Zealand was part of a comprehensive plan by central government to nurture contemporary art practice in New Zealand. The goal was to increase the awareness of, and demand for, New Zealand art both here and overseas.2

Enter Barbara Brooke – a woman deserving of our attention when it comes to recalling those who anticipated and worked for the needs of New Zealand artists. Barbara was born in 1925 and grew up in the Christchurch suburb of Belfast, where her parents Alexander and Mary Anne Brown owned a grocery store. In 1945 she married André Brooke, a modernist artist and self-taught architect from Hungary. Together Barbara and André opened the first contemporary art dealer gallery in Christchurch in 1959 – Gallery 91. Barbara’s passionate support for contemporary New Zealand art never left her, and she went on to sustain a twenty-year career as an arts advocate.

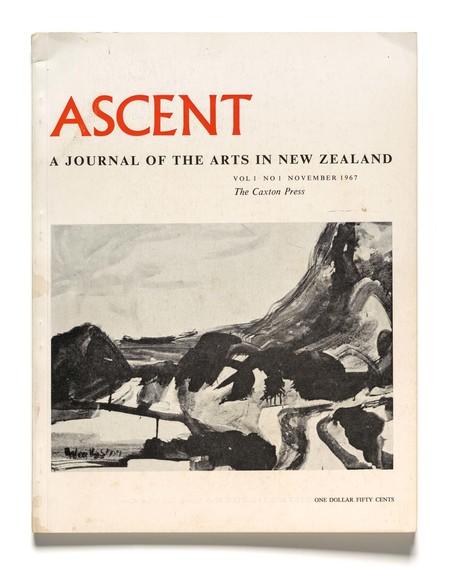

In 1966 Brooke was employed part-time at Caxton as editor of the New Zealand Local Government Magazine, but her role became full-time when she and Leo Bensemann launched Ascent in 1967. They provided subscribers with knowledgeable, informative and, importantly, critical art writing; high-quality reproductions of artworks were coupled with stylish typography and design. Ascent ran for just five issues, being published between 1967 and 1969 only.

There were other arts periodicals, such as the Auckland City Art Gallery’s The Gallery Quarterly and Arts and Community, published by Harland Baker Publishing; in the late 1960s The Gallery Quarterly had a plain format, generally with one informative article, and Arts and Community covered the arts broadly with a community focus – it was more of a national ‘newsletter’ for the arts.3 Ascent also differed from Caxton’s literary magazine, Landfall: it was a larger publication, with a new layout, new typeface, and the added aesthetic enhancement of images on high-quality paper – some of which were in colour.

Ascent: A Journal of the Arts in New Zealand, vol.1, no.1, November 1967, The Caxton Press, Christchurch

Ascent was an early attempt to record a functioning national art community, providing context so that artists no longer practised in a vacuum. As Peter Tomory, former director of the Auckland City Art Gallery, noted in 1969, in New Zealand ‘everyone interested in the arts knows everyone interested in the arts’.4 This interconnected nature of the New Zealand art community was cleverly utilised and then reported on by Brooke and Bensemann.

The absence of professional arts criticism and commentary in the country had been described by Tomory as obstructing the development of artists’ practice. In 1958 he wrote: ‘Serious art can flourish only if there is strong, informed criticism to sweep away the dross and explore what is good.’5 Ascent was an attempt to rectify this. It was an elitist academic magazine of its time and Brooke and Bensemann carefully selected their contributors. Before the first issue was published Bensemann confided in his overseer Charles Brasch: ‘I may be foolish in imagining it’s possible to make the issue visually sound – but at the same time I must restrict it in view of costs involved … God only knows what sort of response I’d get for articles – it makes me tremble.’6 The writers chosen to fill the columns of Ascent included academics, current and former public gallery directors, artists, poets and playwrights.

Brooke’s determination to support contemporary New Zealand artists is made all the more remarkable when seen in context of the decade in which Ascent was published. The year Brooke was employed at Caxton, just thirteen per cent of New Zealand women held positions that were then considered ‘new for females’.7 As the first female editor at Caxton8 she broke new ground in a working environment that was male dominated and likely to be chauvinistic.9

Ascent was propelled by Brooke’s leadership and expertise. She was the perfect person to edit a New Zealand art magazine: she was already travelling for Caxton with the local government magazine, and her previous roles meant she had connections with artists throughout New Zealand, and knowledge of contemporary art and its practice. Ascent’s editorial was primarily Brooke’s responsibility and her contributions were complemented by Bensemann’s own knowledge of New Zealand art, typography and design.

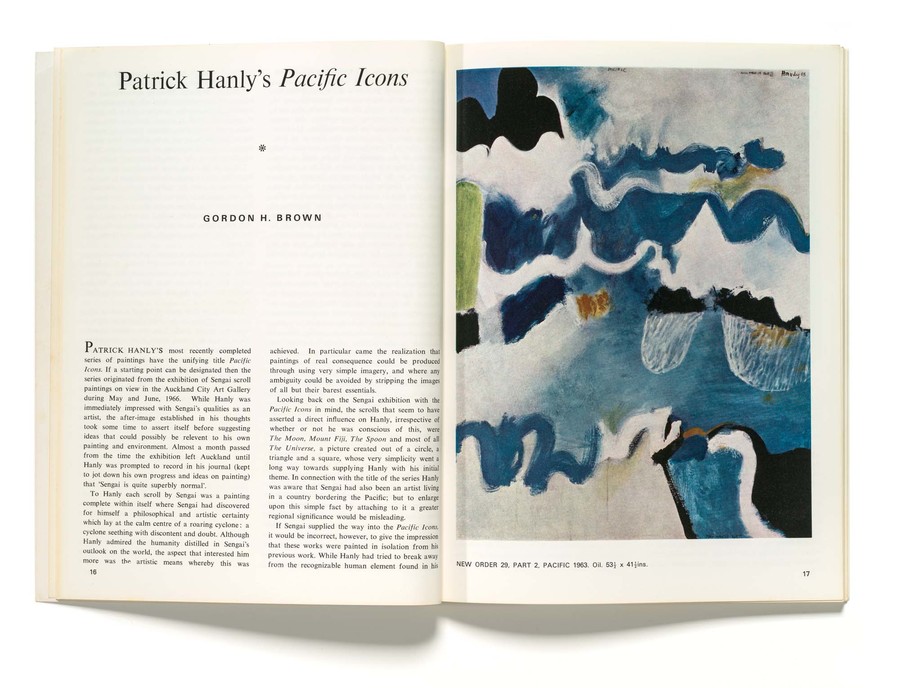

Brooke’s devotion to contemporary artists was fundamental for their exposure in Ascent. She included artists that Bensemann was reluctant to profile – he was not a supporter of New Zealand modernism. His disdain is captured in a letter to Brooke in the late 1970s: ‘the McDougall [Art Gallery] is stuffed full of … Hotere, who must be showing at least 500 large [paintings] of crosses … covered with crudely stencilled messages … They are boringly repetitive.’10 Equally, Bensemann was known for having little time for Tomory.11 So it is an illustration of the esteem in which Brooke was held by her colleagues that Tomory still wrote for Ascent and Ralph Hotere’s work featured on the cover of Ascent no.3 – which also included a review of his recent exhibition. Indeed, alongside the work of Hotere, Ascent contained non-figurative artworks by Shay Docking, John Drawbridge, Roy Good, Patrick Hanly, Colin McCahon, Milan Mrkusich and Gordon Walters.

Sales, however, were slow, and promises for funding from the Arts Council unfulfilled. Publishing Ascent was a struggle. Brooke helped meet costs with a creative idea that ensured the journal could afford coloured images. She wrote to public art galleries throughout the country asking for sponsorship of colour blocks in return for printing 200 gift cards of the image for the sponsor’s own use.

Indeed, Brooke’s innovation sparked support from the Robert McDougall’s early director, William Baverstock – and while his support was not surprising, the reproduction he agreed to sponsor was. In the late 1940s Baverstock had been a key figure in the Canterbury Society of Arts’ decision not to purchase Frances Hodgkins’s Pleasure Garden (1933). It was a conservative rejection of modernism that was only overruled in 1951 when the watercolour was finally accepted into the McDougall’s collection. Astonishingly, in a letter dated days after his farewell as director, Baverstock consented to sponsor a reproduction of the same painting and have the colour cards produced.12 This decision possibly marked a change of heart on his retirement, perhaps prompted by the last exhibition he oversaw as director – The Origins of Frances Hodgkins in 1969.13

Pleasure Garden featured in the fifth and final issue of Ascent, which was a tribute to the centennial of Hodgkins’s birth, published in 1969. Brooke’s former colleague Robin Alborn recalled: ‘the Queen Elizabeth Arts Council … had their feathers clipped on spending … Ascent and New Zealand Local Government ... we pulled the rug on it all about the same time.’14 The loss of such an art magazine left a void, but led the way for magazines such as the Bulletin of New Zealand Art History (later the Journal of New Zealand Art History) which began in 1972, and Art New Zealand, which was launched in 1976.

Brooke devoted her life to supporting New Zealand’s contemporary artists. When it was still early for women to hold managerial positions, Brooke had already managed a dealer gallery and an Arts Society. She was tireless in her efforts. In addition to opening Gallery 91 and her work with the Canterbury Society of Arts and the Caxton Press, she started the first craft market in Christchurch – the Mollett Street Market – with three friends in the early 1970s,15 then she opened the Brooke Gifford Gallery with Judith Gifford in 1975. Brooke lost her life to cancer only five years later. Bensemann wrote to her mother: ‘I only hope that the respect and high regard in which she was held by the art community throughout New Zealand may be of some comfort to you. … [P]eople of her ability and brilliant personality are rare indeed.’16