The Art of the Heist

In early August of 1977, two students from the University of Canterbury School of Art walked into the Robert McDougall Art Gallery, took a painting off the wall, and walked out the front door. After lunch, the director Brian Muir noticed a 7 by 9 inch painting was missing.

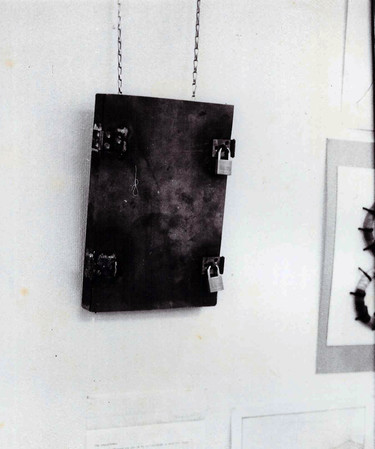

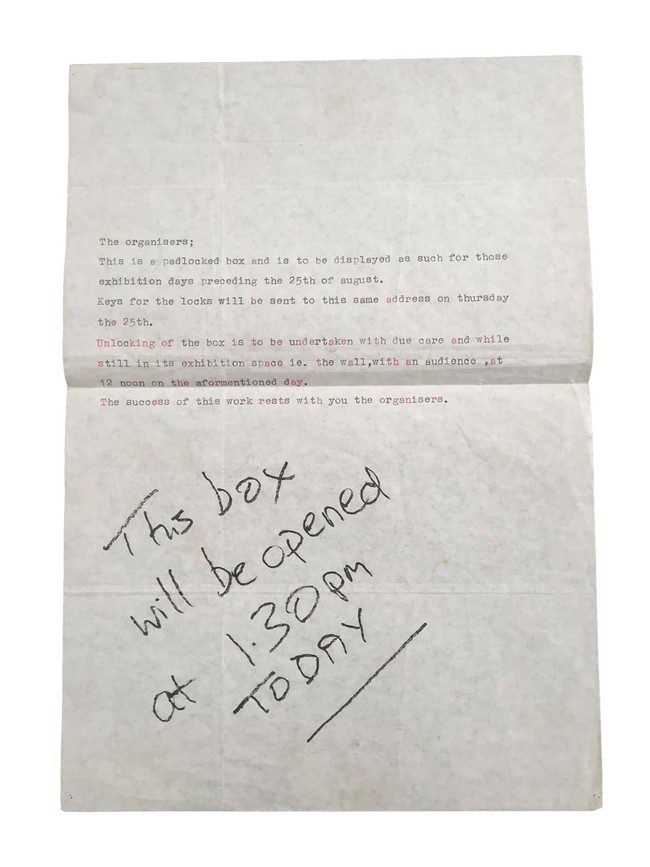

Shortly afterwards, at the National Art Gallery (NAG) in Wellington where I was the exhibitions curator, I received a phone call from Muir informing me that Raymond McIntyre’s painting Suzette had been stolen and asking me to be on the lookout for it. The theft had not been made public. Two days later, I received a small wooden crate in the mail. Inside was a custom-made, 8 by 10 metal box. There was a note on the box with instructions – the artists who had constructed the box would reveal its contents at the opening of the A4 Show in a gallery on Willis Street.

The 1977 Students Arts Festival

John Davis was the director of the 1977 Students Arts Festival. He had invited Andrew Drummond, then education curator at NAG, and me to run the visual arts programme for the festival. John was the quintessentially charismatic student leader and he gave us enough money and freedom to do what we wanted. Andrew and I approached our director Melvin (Pat) Day, who readily agreed to loan us out. Pat always stood by us and encouraged our non-traditional approach to the arts. A graduate of the Courtauld Institute of Art at the University of London, Pat was old school; he wore perfectly hand-tied bow ties, told charming and witty anecdotes and was a sound art history scholar. He died last year at the age of 92, doing what he loved most, painting.

We organised several events around the Arts Festival. A video store on Lambton Quay was rented and crammed with borrowed video equipment that students could take on location to explore new technology with big clunky cameras and tape recorders. They then presented their grainy black and white videotape at the store. A performance space in a gallery on Willis Street showcased student artists and their installations; Bruce Barber, Brian McNeil and Arthur Baysting’s persona Neville Purvis performed there. The Elva Bett Gallery on Cuba Street hosted a photo/documentary exhibition called Closed Coal Camp Island by Yuji Saiga and there were other exhibits around Wellington, including a show of Jos Carlin’s dance photography at the Memorial Theatre.

Then there was a national student open invitational called the A4 Show. Any student could submit anything the size of an A4 sheet – 210 x 297mm, or about 8 by 10 inches.

In 1976, I had organised an exhibition called Art in the Mail that was launched at the Manawatu Art Gallery by Luit Bieringa. The show toured ten major galleries in New Zealand with Arts Council funding, then went on tour in Australia. For all I know, it is still touring somewhere. The show upset an extraordinary number of people and generated record crowds. The idea was to remove the curator from the art show and allow artists the freedom to show their work, uncensored. Long before the internet, Art in the Mail allowed for open unfiltered communication through the postal system. The A4 Show worked on a similar principle.

So, the day before the deadline for submissions, we received this mysterious metal box at the NAG. We had to show the work as it fulfilled the requirements for entry. The box had special padlocks but no key. The submitting students would be present at the opening of the show and unlock the box.

The Curator’s Dilemma

I had my suspicions about the contents of the box. Could it be the painting? I had to find out. I called a locksmith to come to the NAG after hours, and in one minute he had picked the two locks.

When he left, Andrew and I lifted the lid and there, encased in bubble wrap, was a beautiful little oil by a leading expatriate New Zealand artist. Painted around 1914, Suzette captured a young woman in a black hat, leaning on a table, her pinkie between her sensual lips, her eyes gazing into the distance, pensive but evocative. If you had seen her at a bar in London or Paris you would have known she was both alluring and trouble, but now, sixty-three years later at the National Art Gallery, she was our trouble.

What to do with the stolen painting? Would we respect the wishes of the artists or the ethics of a curator? Should we help a director who could lose his job over the theft or further the careers of two art students?

And what would the painter have thought? Raymond McIntyre (1879–1933) had travelled to England in 1909. He was from Christchurch and had taught at the Canterbury College School of Art. Would he have been amused? Maybe he would think this a kick in the pants to the conservative art scene? At least he would have admired the craftsmanship of the metal box and the daring of the heist.

Behind the hardwood painting was an envelope. A series of Polaroids showed the painting on the gallery wall; the painting being lifted off the wall by a student dressed in a trench coat, dark glasses and fedora; and the empty space on the wall where the painting once hung. The last shot was of the student walking out of the gallery, the painting under his coat.

I picked up the phone and called Brian Muir in Christchurch. It was an understatement to say he was relieved. I then called our gallery photographer who was instructed to produce an exact copy of the painting and mount it on similar board. Muir arrived the next day and took possession of the painting. He admired the photographic reproduction compared to the real painting. He agreed not to prosecute the two students, and not to display the painting until after the A4 Show had closed.

The Opening of the A4 Show

The two students from Christchurch arrived at the opening. I took the key from them and walked to the back of the gallery where the padlocked metal box was displayed on an easel. The gallery was packed, standing room only, and the two art thieves were forced to remain at a distance. Andrew operated a large video camera (on loan from our video store) to document the proceedings.

I don’t think the audience was as interested in my ‘curator as art rat speech’ as they were in what was in the metal box. When I finally unlocked it and held up the colour reproduction, the two students at the back did not realise they had been victims of a switch. Suzette gazed out into the crowd, nonchalant at being a reproduction. She still looked original. The metal box with the reproduction inside and the Polaroids remained on display and attracted a lot of interest and debate.

Later Andrew and I talked to the two ‘art thieves’, who finally understood they had themselves been victims of a heist and that we had, in fact, protected them. They had planned to return the painting to the Gallery after the show; the fact that we would have displayed a known stolen painting, that the painting would have been recovered, and that they would have been prosecuted for theft, were details they had not thought through.

The entire heist was part of their graduate submission and their lecturer at Ilam, Tom Taylor, was in possession of a sealed letter to be opened in case of their arrest. The presiding magistrate would not have appreciated their attempt to involve an early twentieth-century New Zealand masterpiece in an extended performance piece. The colour reproduction and the metal box were given back to the students, who needed it for their submission. They graduated with honours.

Raymond McIntyre Suzette c.1914. Oil on wood panel. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, presented by Mrs M. Good, London 1975