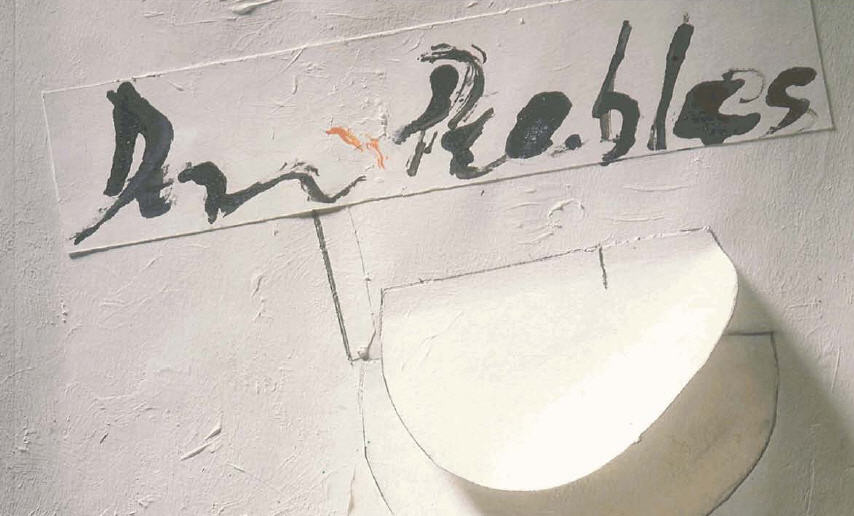

Don Peebles Relief Construction No.3 1972. Enamel on wood with plastic. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1973

Don Peebles: A Free Sense of Order

There’s a wonderful film on Don Peebles in the Gallery’s archive that provides a fascinating insight into the artist’s practice.1 Produced around 1980, it shows Peebles working in his studio and walking through his garden, past the fruit trees to his shed down the back, with an audio interview overdubbed. My favourite scene shows the artist in the shed with a box full of various wooden shapes that he has collected over the years, which he takes out and loosely assembles on a small sheet of plywood – a free sense of order created out of these seemingly random pieces.

As an art history student in Christchurch during the 1990s I saw several exhibitions at the Robert McDougall Art Gallery that I still carry around with me, among them the excellent Don Peebles survey Harmony of Opposites. It was the artist’s relief constructions from the 1960s that really captivated me and repeatedly pulled me back to the Gallery for more.

I never got to know Peebles – my experience is limited to a single conversation with him and Barry Cleavin at an opening in town one night. The pair were in full flight, which was something to behold, both extremely articulate and with a wicked sense of humour – they obviously enjoyed each other’s company immensely. Fortunately for the art historian, Peebles was very comfortable talking and writing about his art. He knew what he wanted to say and could express himself with clarity and precision.

Peebles’s interest in art was given a boost when, in 1945, having served with the New Zealand Army in the Pacific and Italian campaigns of World War II, he was able to study briefly in Florence before returning to New Zealand. He continued his studies at home, both at the Wellington Technical College Art School and the Julian Ashton Art School in Sydney, and by the late 1950s his work had evolved from Cézannesque landscapes to a more distinctive abstract style. Features of the landscape, such as the grey concrete metropolis of his Wellington series, seemingly dissolve out of focus in thick layers of paint, which is applied with a palette knife in a manner reminiscent of the post-war Tachisme style.

In 1960 Peebles was the first abstract artist to be awarded the Association of New Zealand Art Societies Fellowship Award. The fellowship enabled him to leave his job at the Post Office in Wellington and to travel to England to study and make art full-time. Prior to the trip, Peebles married Prue Corkill, his constant companion and supporter for the remainder of his life. It was an event which he summed up in a characteristically succinct manner: ‘I proposed on a Friday, we got married the next Tuesday, and sailed for England on the Wednesday.’2

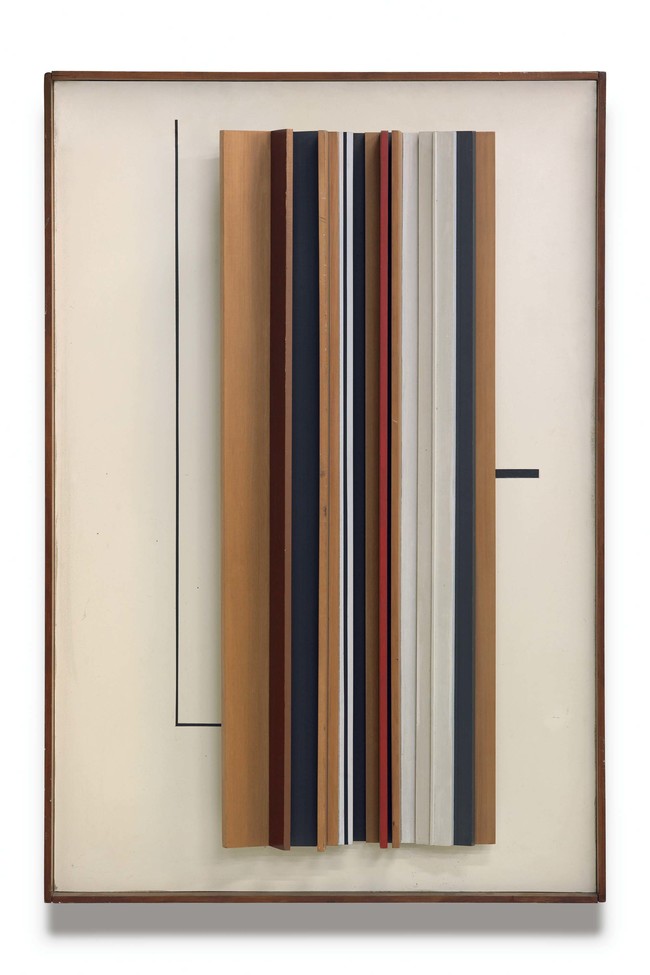

Don Peebles Relief Construction: yellow and black 1966. Painted wood on panel. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased 1966

One of the good things that happened when I got to London, was the realisation that I was there to learn. I told myself that I should try, as much as possible, to drop the attitudes and the ways of working I had pursued back in New Zealand. It was time in which I could let myself go. Experiment.3

Shortly after his arrival in London Peebles fortuitously came across an article by Victor Pasmore, one England’s leading abstract artists of the post-war period, titled ‘What is abstract art?’4 Pasmore argued that for abstract artists to develop their art fully they ‘must move from the two-dimensional medium of painting to the three-dimensional world of sculpture, “construction” or pure architecture.’5 Pasmore’s art appealed to Peebles:

[Here] were works that made no obvious reference to visual reality as we would normally understand the term. They were very, very logical but highly inventive images […] totally abstract and yet at the same time there was a familiarity about them. That and also the lack of decorative incident, the clear direct and overt sort of way in which these works activated the space around them without any attention being given to triviality.6

One cannot underestimate the effect of Pasmore’s article on Peebles and his art – he himself described it as being ‘like a kick in the guts’. His work headed in a brave new direction, canvas was replaced with hardboard, and timber and Perspex were cut and assembled on the surface.

I enjoyed what [Pasmore] had to say so much that I wrote to him, and he responded by sending an invitation to the opening.FTN-7 That was how I met him. Later I occasionally took work around to show him at his Blackheath studio. The whole three dimensional thing was very exciting to me – that’s really how I got into making the reliefs and constructions I did during that time. The whole time I was in England I did drawings and reliefs, I hardly painted at all. I was totally absorbed in this constructive process, and yet it was something I don’t think would have happened if I’d stayed in New Zealand.8

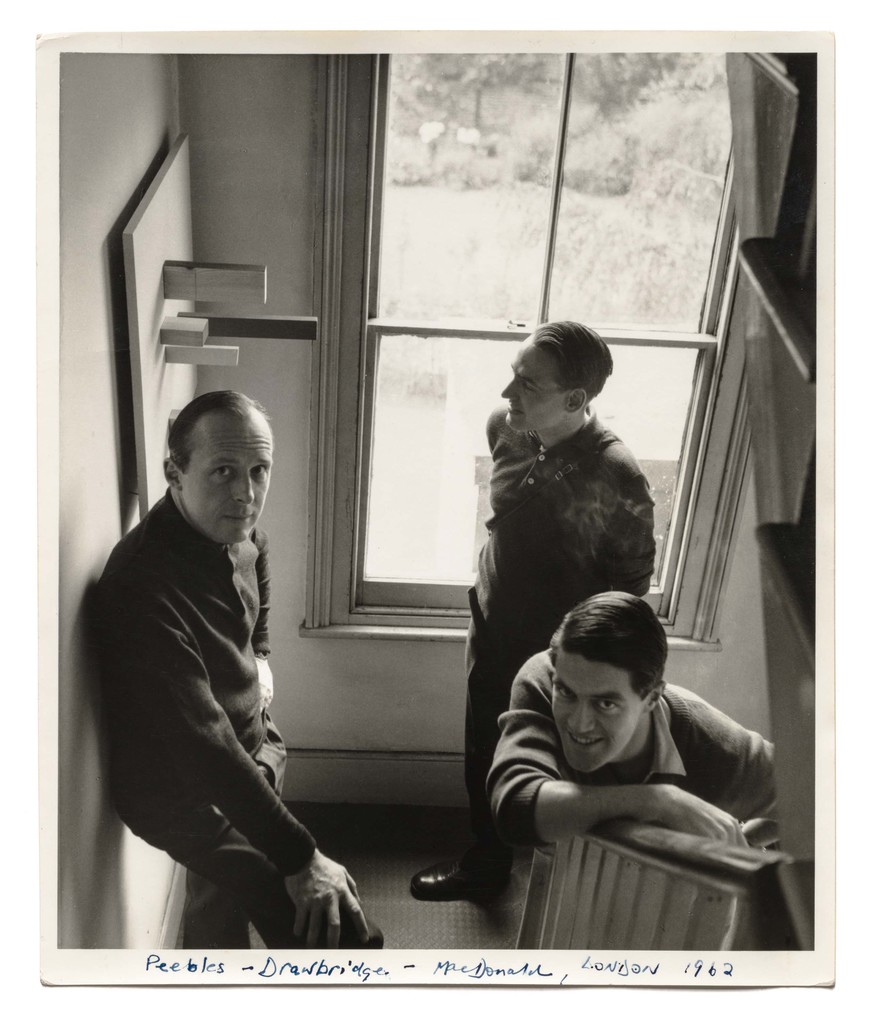

The artist’s new relief constructions formed part of a lineage stretching back beyond Pasmore to an earlier generation with an interest in constructivism, including Ben Nicholson and László Moholy-Nagy. But more important was his immediate contact with Pasmore and experiencing relief constructions by his British contemporaries such as Anthony Hill and Mary Martin. Indeed, Pasmore invited Peebles to participate in an exhibition of constructions and collages with artists including Hill at the Aldeburgh Festival in 1962.

Don Peebles, Robert MacDonald and John Drawbridge at 5 Nugent Tce, St John’s Wood, London, 1962. Photo: Alex Starkey, FRPS

Much of Peebles’s work did not return with Don and Prue when they made the trip back to New Zealand in 1962, but the artist immediately set to work creating new relief constructions. One of his first exhibitions back in New Zealand was held at Wellington’s Centre Gallery in 1964. Some visitors to the show felt that Peebles was making a false start with the construction reliefs but his close friend Don McKenzie rose to his defence in Landfall 70: ‘In view of his constant concern for structural relations and his trend towards even greater simplicity (allied appeal of colour) Mr Peebles inevitably began to paint in the tradition descending from Mondrian.’ McKenzie argued that the difference between Peebles’s relief constructions and his earlier paintings lay ‘only in the gradual but consistent paring away of incidental effects and outworn problems, and in greater concentration on the fundamental challenge to create new life in accordance with the logic that does not correspond to the visually familiar but to an internal dynamic brought into being almost at the very moment the materials are chosen. At this point of refinement, abstraction ceases and construction begins.’9

For the next decade Peebles explored the endless possibilities presented in assembling his relief constructions. Alongside these he continued painting on canvas, producing works including the rigid and geometric Canterbury and Linear series, but it is the relief constructions that, for me, were most successful and continue to resonate. The construction reliefs had become more and more refined by the time of his large survey exhibition at the Canterbury Society of Arts Gallery in 1973. This point is highlighted by examples such as the Gallery’s Relief Construction No.3 (1972) and its companion work from the Dowse Art Museum’s collection Relief 1 (1972). These works have an intensely austere, measured quality – a flat field of white, evenly spaced plastic strips and precisely painted black lines.

Peebles wrote an ‘artist’s comment’ to accompany the Canterbury Society of Arts exhibition:

Construction, for me, is not a style but simply a method. Neither my reliefs nor my paintings derive from any strict mathematical basis but are assembled with a free sense of order, more characteristic of the painter, than of the function-influenced architect or designer. The narrative aspects of art are of less interest to me than the more purely visual and private impulses – if such elements as colour, light, line, form, mass, volume are intimately experienced, they too can result in a very personal statement.10

Don Peebles Relief Construction 1966. Painted wooden assemblage. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, gift of the artist, 1991

Discussing abstract art can be a fraught affair because, as Peebles mentions above, it is such a personal and private response. One often cannot be sure of the artist’s intent – Peebles once commented: ‘I was once asked by a person at an exhibition of mine what my works meant? And I said “I do them, I don’t accompany them.”’11 But personally, what I find so appealing about Peebles’s relief constructions is the profound sense of order and calm they provide amongst the chaos of nature and life. I like the quietness that gently reverberates from these works, the way they step out off the wall – not just two- or three-dimensional but, as Don McKenzie pointed out, even four when they cast shadows.12

Perhaps it was this quietness, this orderliness, that brought about a change in the artist’s work from the mid 1970s. His relief constructions began moving away from the flat, defined areas of colour and exposed plywood he had been using for the previous decade to feature more expressive paint work as he reconnected with the painting process. By the late 1970s he had begun painting the multifaceted canvas reliefs for which he is best-known today. Peebles stated that he felt a need for change – his construction reliefs had become increasingly distilled until he felt he had refined the guts out of the idea, he needed to return to his ‘painterly interests and the use of colour and now these canvas reliefs in a way seem to bring together the constructive 3-D element and the painterly colouristic … negative and positive project from an assembly and so forth.’13

Never one to sit still, Peebles was continually striving to develop his art, constantly looking at ways of challenging himself, just as he did when he first arrived in London in 1960. As he once said ‘I want to be almost totally out of my depth all the time … swimming to the surface, not floating on top and gradually sinking.’14