Jonathan Mane-Wheoki: teacher

There are some teachers you remember all your life: extraordinary individuals who view learning as a boundless source of energy, both for themselves and their students. This sort of teacher has not only total command of their subject, but an infectious enthusiasm for it that transmits itself to the minds of others. Teachers like this create advocates for their subject. They impart knowledge, but more importantly they show you a way of being in the world. It's a rare teacher who teaches you how to learn, but Jonathan Mane-Wheoki was one such individual.

'No question is stupid if you want to know the answer'

Jonathan died recently in Auckland after a long illness. At his requiem mass, held at Holy Trinity Cathedral in Parnell, I looked around the many hundreds of people who had assembled for the occasion – and the range of prominent roles in the fields of art and culture they represented – and realised just how many had either been taught by Jonathan or had been lucky enough to be mentored by him. He taught on the art history programme at the University of Canterbury for thirty years, seeding the next generations of art historians, curators and writers; he assisted young Māori artists through his work with the Māori Education Foundation; and he was a role model and mentor for younger academics, particularly those of Māori and Pasifika descent. He was a person who would not only open doors for you, but give you a gentle push through if you needed it, and he continued to keep you within the ambit of his view for years to come.

He also had a long association with the Gallery, and one of my first acts as newly appointed senior curator was to arrange an interview with him for Bulletin. He had recently spoken about his life and faith on Radio New Zealand's Spiritual Outlook programme. He pronounced himself relaxed about his impending death ('What else could I be?') and described the joy he was taking in making arrangements for his requiem mass, and for the tangi at which he would be laid to rest beside his father at his marae, Piki Te Aroha at Rāhiri in Northland. Recalling that Ralph Hotere was transported on his final journey in a black Hummer, Jonathan said that he had arranged a rental van ('a modest people-mover') to take his body north. 1 When I went to see him in Auckland in early September, at the mid century house he shared with his partner Paul Bushnell, it was with the knowledge that there was not much time left.

'I don't regret one second of my years of teaching,' he told me. I mentioned his achievements as an academic – the change in scope of the two-year art history survey course from a Eurocentric focus to a global perspective, the establishment of a contemporary Māori art history paper, his appointment as dean of music and fine arts at the University of Canterbury and later head of Elam School of Fine Art in Auckland—but it was clear to me that it was the act of teaching itself that he most valued. Appalled by academics who hated teaching and dodged undergraduate lectures, he said that the best teachers should always teach from stage one, 'to encourage and captivate students and enthuse them about the subject'.

His own first teacher was Colin McCahon. When Jonathan's family moved to what E.H. McCormick described as the 'sylvan slums' of Titirangi, he became friends with the McCahon children, and vividly recalled McCahon painting the Northland Panels (1958) on the back deck of their house one summer afternoon. 2 He became an artist himself, studying first with McCahon in night classes taught in the attic of the Auckland Art Gallery during the 1950s, and secondly with Rudolf Gopas at the UC School of Fine Arts in the mid-1960s. 'Colin McCahon and Rudi Gopas opened me up to two very different worlds of art,' he told me. 'They were great teachers because of the example they set as painters. McCahon, though, said that the painter's life was exemplified by R.N. Field. Of course, many people later said the same about McCahon.'

While a student in Christchurch, Jonathan visited the Robert McDougall Art Gallery often to look at McCahon's Tomorrow will be the same but not as this is (1958–9). Painted at about the same time as the Northland Panels, it provided a tangible link to his own history as well as an ongoing metaphor for ideas about creation – both spiritual and artistic – through the cleaving of light from darkness. After graduating with a diploma in fine arts and a degree in English, he worked in 1971–2 as exhibitions officer/assistant to the director at the McDougall, developing programmes and organising film screenings that included pioneering New Zealand film-maker Rudall Hayward's feature Rewi's Last Stand (1925/40). When he left Christchurch for London to study at the Courtauld Institute of Art, he credited his experience talking to public visitors at the Gallery with his newfound 'surprising confidence' in academia: 'I was always so reticent at Canterbury.'3

Within the Gallery's archives is a large file of Jonathan's correspondence home to the McDougall's director, Brian Muir. 'Brian,' he writes not long after arriving in London, 'It strikes me that one or two items a year might strengthen certain sections of the McDougall's collections – in particular, graphics old and new. Valerie has a gorgeous stripey Bridget Riley screenprint and a super Alan Davie. I have been trying to con ex-Chch students in London into subscribing a small amount to a picture fund so you may be receiving gifts from time to time.'4

In a subsequent letter he provides a wish list of purchases for Christchurch, based on works that he has seen for sale.

Suppose I had a million dollars to spend on paintings for the McD Gallery: what would I buy? A modest Cézanne watercolour, a beautiful Monet, a super Roualt regions-landscape painting (absolutely fabulous!), a modest but typical Renoir, an early Kandinsky, and Breughel's 'The Four Seasons', plus 4 or 5 Goya etchings, a Pechstein lithograph, the Cranach ptg, the Corneille de Lyon, a Henry Moore sculpture (a small one), a Klee drawing. In many ways I wish I were still in Ch.ch so that I could get a fund going. It is going to be so important to have these works in Chch. When Art History is taught in the University. WHEN... 5

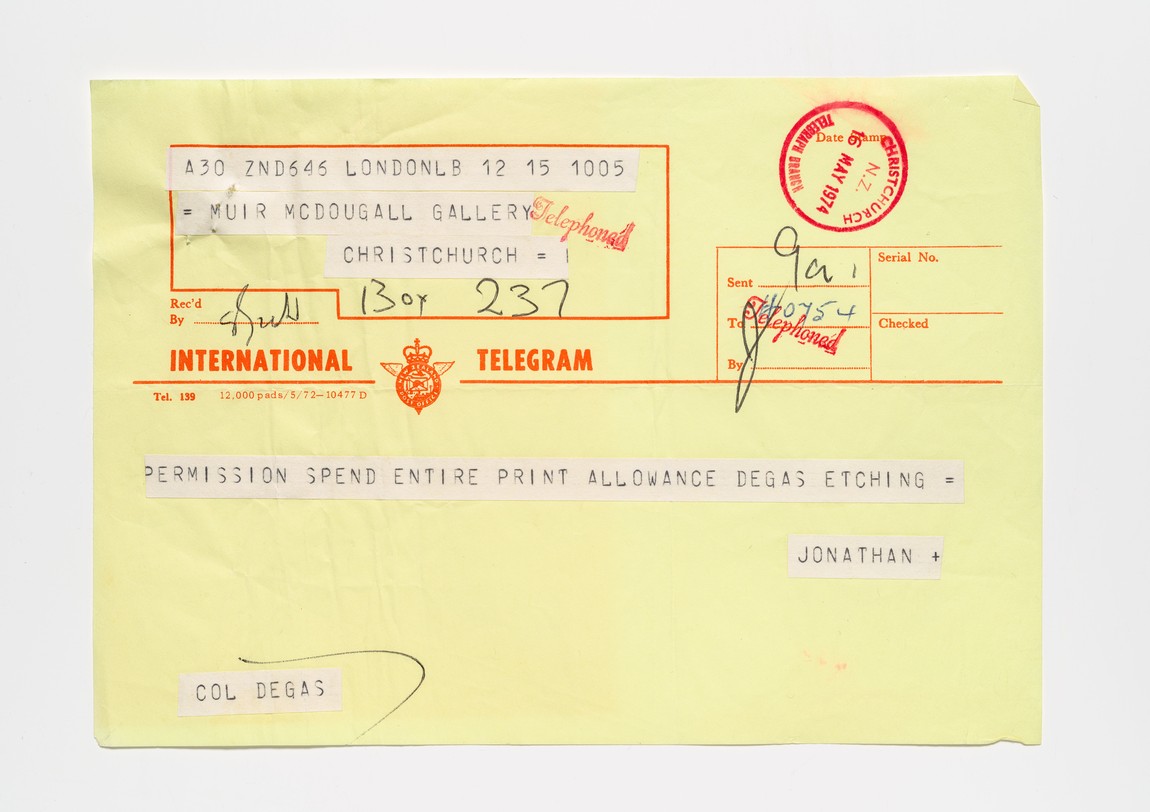

Brian Muir seized the opportunity to secure Jonathan's services as a London-based agent for the Gallery; provided with a budget and modest annual stipend, he located and recommended potential works for the collection. Many important acquisitions were made for the city by Jonathan over this period, including Andy Warhol's 1972 screenprint Mao Tse-Tung ('powerful, completely convincing, technically marvellous, a devastating image' 6 ), which he saw on a trip to Oxford and noted had also been selected for the British Arts Council's collection; Bridget Riley's Untitled (Elongated Triangles 4) (1971), and a version of Antoine Coypel's Venus and Adonis, as well as works on paper by Degas, Cézanne, Corot, Piranesi, Lucien Simon, Karel Appel and others. Within the archive is a telegram asking for urgent permission to spend the entire year's print budget on the Degas, which was granted.

At the Courtauld, Jonathan was taught by the eminent art historian and Keeper of the Queen's Pictures, Anthony Blunt, later exposed as a Russian spy, whom he remembered as a brilliant teacher; and by Alan Bowness who went on to become director of the Tate Gallery. 'They knew their subject and were passionate about it,' he told me, comparing them as teachers with McCahon and Gopas. 'You knew, as a student, that you were getting the real deal from them.' He did some teaching himself, and recounted to me one particularly resonant moment, with a group of students from Grinnell College at the University of Iowa:

Those kids gave me my basic precepts for teaching. Odd little things. I remember one day a student said to me:

'May I ask you a question?'

'Of course,' I said.

'I feel stupid because I don't know the answer,' she said.

'Well, do you want to know the answer?' I asked.

'Yes.'

'No question is stupid if you want to know the answer.'

In 1975 he returned to Christchurch as a lecturer on the recently-established art history programme at the University of Canterbury. His area of speciality was Victorian church art and architecture, the subject of his master's thesis. He had realised, to his surprise, in London that he was already familiar with the vocabulary of Victorian ecclesiastical architecture from the wooden colonial churches of New Zealand; teaching in Christchurch, he incorporated the Gothic Revival buildings of the South Island in his lectures and field trips.

A second transformative moment came in the early 1980s when his father Hetiraka died and Jonathan took his body home to the Far North.

I went through all that fantastic experience of the tangi and that changed me or released something in me that had been dormant. From that point onwards I began to feel that it was payback time for my ancestors. I began to develop my thinking about Māori art and that's what eventually led me to a huge involvement with Māori contemporary art. Little by little I've come round from being an internationalist in the European sense of an art historian to an unashamed regionalist art historian who's anchored in the Pacific, trying to make sense of the world from that perspective. 7

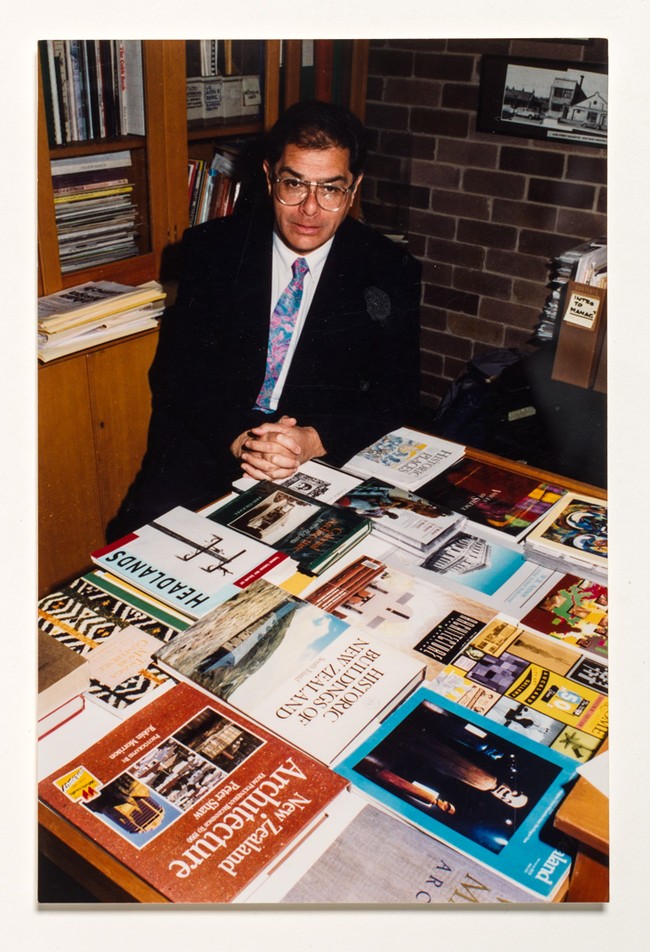

Teaching, then, as a process of making sense of the world, a process of creation for both the teacher and the student: teaching as a process of learning. Jonathan gradually began to incorporate an expanded world view into his academic teaching, developing new courses to deal with the problem of the acceleration of history and to explore indigenous art histories. In 1992 he was appointed as kaitiaki Māori/curator of Māori art at the Robert McDougall Art Gallery, a position he held until 2004 when he left the university to become director of art and collection services at Te Papa Tongarewa. He co-curated several exhibitions for Christchurch over these years, including Aoraki/Hikurangi (2004), HIKO! New Energies in Māori Art (1999), and Te Puawai o Ngai Tahu, to open the new Gallery building in 2003.

'You must love your students. You must love your subject. Without love, you can only hope for perfunctory results.'

Even before shifting out of the university environment, Jonathan developed a role as a public intellectual, moving back and forth between the academy and the broader realm of museums and art galleries. His research interests continued to range from Victorian colonial architecture to contemporary Māori and Pasifika art – but were always, in one way or another, concerned with the connection of people to place, the expression of identity and with the broader agency of art within our culture.

Head of the Elam School of Fine Arts at the University of Auckland from 2009 to 2012, in 2013 Jonathan returned to Te Papa to take up the position of head of arts and visual culture. He was made a Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to the arts in this year's Queen's Birthday Honours and in late September was awarded a medal as Companion of the Auckland War Memorial Museum. He was awarded the Pou Aronui Award from the Royal Society of New Zealand Te Apārangi in 2012 in recognition of his outstanding contribution to the development of the humanities in Aotearoa New Zealand. Beyond his contribution as a scholar, however, what might be counted as his ultimate legacy is his example to others: his daily demonstration of how to be an art historian, in a way which encouraged and inspired many others to join him.

I asked him, towards the close of our conversation, what made a good student.

'Constant questioning and self-criticism. Good students make a contribution to a dynamic environment. And are prepared to take risks, which includes not always agreeing with your teacher. Teachers need a degree of humility: students need a certain amount of arrogance. All within the bounds of good manners, of course.'

'What makes a good teacher?' I asked the best teacher I've ever had.

'You must love your students. You must love your subject. Without love, you can only hope for perfunctory results.'

Senior curator Lara Strongman talked to Jonathan Mane-Wheoki in Auckland in September 2014.

All photographs supplied. Archive documents are from the collection of Christchurch Art Gallery, Robert and Barbara Stewart Library and Archives. The texts that follow are the complete versions of the quotes found in the print version of Bulletin 178.

He altered my perception of Māori forever. Growing up and seeing images in the media of Māori as troublemakers in society, made me embarrassed about revealing my Māori heritage at school. That changed when as a student at UC, I heard a lecture by Jonathan. He was refined, intelligent and articulate, and what’s more, he oozed mana. I couldn't believe he was Māori. Later on I found out he was from the same tribe as me, this gave me a tremendous sense of pride... I was related to him somehow. That same year he called Kirsty Gregg and myself into his office to see how he could be of support to us. Since then I have experienced his kindness, warmth, wisdom, support and love. Ki aroha me te whakawhetai, Jonathan.

— Darryn George, artist

Many of my strongest memories of Jonathan remain my earliest. To a young student with very little knowledge of or background in art and its history he was a revelatory teacher – interested, encouraging, challenging and intellectually authoritative.

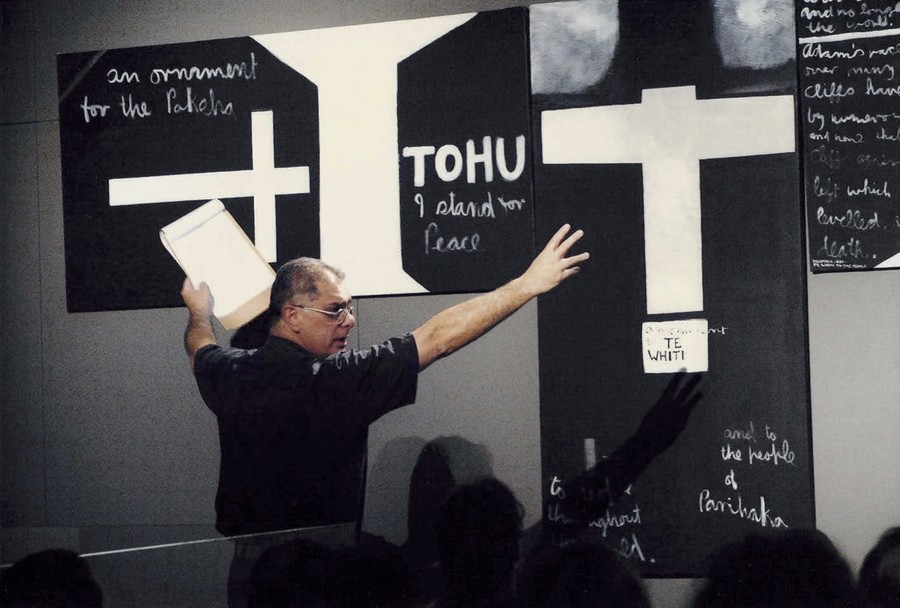

I’ve noticed in recent days how he was so often photographed, arms wide before an artwork, as if not only directing the attention of his audience but addressing the very heart of the work itself. These images reinforce the memory of his oratory presence as a teacher. But they also bring back to mind his clear, crucial exhortation to we his students to look. Look at the work in front of you. Look, think, discuss. And then always look again. Look long and hard and recognise that only through looking will pleasure, understanding and meaning form. And once you think you may have found some element of all three, and perhaps talked or written about it, return to the work and look yet once more in order to test those ideas, extend those experiences.

Jonathan was an extraordinarily disciplined art historian who instilled rigour and fostered a spirit of intellectual curiosity in his students. He began with the artwork, reached out to consider the peoples and cultures surrounding it, and then returned, always, to the art. That's the lesson I'll always remember – always take the time to look hard and never stray so far from the artwork as to lose that capacity to look.

— Blair French, assistant director of curatorial and digital, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney

When I arrived at Canterbury in July 1995, Jonathan had embraced his passion for contemporary indigenous arts in the region. He had already contributed to a growing scholarship on contemporary Māori artists, was a member of the Arts Board and Toi Māori, and had championed the idea of creating the Macmillan Brown Artist in Residence program. The Queensland Art Gallery had enlisted his services to curate New Zealand's contribution to their Asia Pacific Triennial, and he was very much involved with the almost complete Jean-Marie Tjibaou Centre Culturelle.

Shortly after my arrival in 1995, I was chatting with Jonathan in his office and he pointed to a box filled with newspaper clippings and suggested that 'there may be something there'... he had been following the beginnings of what I came to call the Pacific Art Movement in New Zealand. He also told me about an exhibition that was about to open and showed me a picture of Michel Tuffery's Povi. Jonathan planted the seed.

The following month, Bottled Ocean (the first major group show of contemporary Pasifika art) opened at the Robert McDougall Art Annex. I was amazed. This exhibition changed my academic career – Jonathan changed my academic career.

This story speaks of Jonathan's generosity. It was not only a box of newspaper clippings that he offered to me. Jonathan took me under his wing; he ensured that I became involved with the Artist in Residence program, he introduced me to the Pacific community; he introduced me to his many communities. We attended conferences and we chatted about issues and ideas. He opened doors. He paved my way as a newcomer into the art historical world of New Zealand.

Jonathan planted another seed as well. He suggested that the best way to start looking at the material he had gathered was to get to know the artists – to establish a community. Now second nature to me, the concept of this kind of 'community' was new to me. I had roughly equated it to networking, but it means more than that... there is a sense of social obligation associated with community – it is something you become a part of, not just something you are associated with. There is a sense of responsibility, a respect, a need to give back, a need to create connections. I have infused this concept, not only into my research and teaching, but into my way of being.

These interactions have helped to create the scholar, the teacher, and person that I have become. They have also had a huge impact on how I think about art in the Pacific, and in particular the importance of that indigenous voice. Looking back, it seems that I had little to do with career Jonathan created for me. I am not only grateful to him for that, but am grateful for the friendship we have developed – one that I will cherish forever. Aloha nui roa uncle Jonathan.

— Karen Stevenson, senior adjunct fellow in art history, University of Canterbury

The teacher shapes their material and creates the threads – lines that exist within a continuity. They also never know or see where these go, and that's just part of the deal. You offered great handfuls of shining threads – pieces to be held, weighed, studied, appreciated, seen. Your 'Worlds of Art' was a highlight of my University Art History 'starter pack', and you certainly knew where to find the threads. I've been surprised at how many of these have since woven themselves into a bigger picture, a larger, shifting pattern.

I'm thankful for your input. I arrived at the School of Fine Arts as an older student to study painting – a mad and risky move – taking on at the same time as many Art History papers as I could. Worlds of Art followed a different trajectory to most other papers – the traditional Western art history model – and also made great use of the resources on hand. How many students knew that an important early work by one of the original Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood stood (as it did) in the centre of our city? Your great use of the local: Roger Fyfe at Canterbury Museum showing West African, Hawaiian and Rapanui (Easter Island) art in their collection stores – truly extraordinary treasures that have stayed with me. A memorable tour of (your) St Michael and All Angels, then (with Jenny May) finding exquisite remnants of this city's once pervasive Venetian Gothic architecture on Cashel and High Streets (with not a clue of what would follow). Your input made the texture of this city far richer. I'd not expected to find so many pieces of your Worlds of Art right here, waiting to be found on our own doorstep.

– Ken Hall, curator, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū

Art is the expression of man's pleasure in labour

William Morris (preface to The Nature of Gothic by John Ruskin, 1892)

Championing Victorian art and architecture, Jonathan entered my life in year three art history. It was 1979 when art history stopped short at 1900 – there was no modern art at Canterbury, yet. But Jonathan's paper brought inspiration and relevance to the stone and brick buildings of Victorian Christchurch, and the galleries in Melbourne and Sydney on the first of the Australian trips. Kind and always energetic, Jonathan tended his art history flock – after all who had ever travelled so far? With an eye for detail and always context he led us through the art and out again to the Victorian buildings, then the interiors, furniture and stained glass. From Pugin and Ruskin to Morris, Jonathan preached the sacred past but also the present.

Years later, Te Papa became the present and it was there again that we met. Our champion for Art, he advocated unceasingly for the national collection, amidst the encyclopaedia of specimens and objects. Over barbeques and drinks and evening functions, he relayed the same message – love for work, for people and always for art.

– Justine Olsen, curator decorative art and design, Te Papa Tongarewa

We were at the McCahon House in French Bay last weekend, something we'd always meant to do and never quite managed until this blustery September morning. Squalls ripped across the harbour, chasing sun and shadows through the kauri on the hillside. And out of the purpose-built cupboards containing audio collages of people who knew McCahon and the house well came Jonathan's voice, talking about growing up along the road in Wood Bay. Almost forty years melted away and I was back in the dark of an art history lecture listening to that voice put words to the torrent of slides pouring off the big screen. I learned to look and to listen, to catch images and connections on the fly, and to write up the notes later, relying on quick mnemonic scribbles caught out of the flow.

In my third year at Canterbury, Jonathan ran his Victorian Art and Architecture course for the first time. We were a small class, maybe eight or nine willing guinea pigs drawn into the close-knit Art History Department near the old Ilam homestead. There was a dinner party at Marcy Bercusson's place in Merivale, for which we dressed up in Victorian costumes of greater and lesser authenticity. There are photos showing Jonathan resplendent in white tie and tails, dancing un-Victorianly in the later part of the evening. There was the field trip to Dunedin, that most coherent example of Victorian civic imagination. And there was the final project of the year, an investigation of the old buildings in Christchurch. Now it was our turn to locate and describe Victorian treasure. I don't remember what the others did, but I still have the portfolio of large format black and white photos of churches, bell towers, schools, municipal and commercial buildings we found and photographed, biking the length and breadth of the city over several weekends.

Most of the buildings will be gone now, lost in the earthquakes. But how vividly a voice issuing from a cupboard has restored them to memory, and thus into the world again. Salve Jonathan, master of the voiced image.

— Michele Leggott, professor of English, University of Auckland

Jonathan's Stage One lectures were lessons in presence as well as art history. Impeccably prepared, they were delivered as performances, complete with provocative assertions and dramatic pauses. Names of artists, works and movements – the trickier the better – were pronounced with relish and each new slide was clicked round with a flourish. His enthusiasm for art and delight in sharing it were infectious.

Later, working with him at the Robert McDougall Art Gallery and the Contemporary Annex, on exhibitions such as Hiko! New Energies in Māori Art and Te Puawai o Ngai Tahu, I was always happy to see the initials 'JMW' appear in my diary. His collaborative style was graceful and low key and he specialised in making perceptive connections – linking people with ideas, with works, with each other. As the Gallery's kaitiaki Māori, he gave his time and tactful, judicious advice freely, and was generous in smaller ways too – once placing his hand on my shoulder during an opening speech and pronouncing me to be 'unflappable', when he well knew I felt anything but.

Most vividly, I remember Jonathan's fabulous laugh, booming out of the Annex office and down the gallery space like a sonic wave, startling the punters and bringing smiles to the faces of the volunteers: reminding us all that art and fun needn't be mutually exclusive.

— Felicity Milburn, curator, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū

I was reminded of how much I enjoyed Jonathan's art history lectures at Ilam in the mid 1990s when I attended Te Papa's Remembering van der Velden Symposium in October, 2013. Jonathan was in his element, speaking on the themes of death and mourning found in the paintings of Colin McCahon and Petrus van der Velden. He always had such confidence and self assuredness when speaking publicly, a confidence that encouraged his audiences to listen and think – at least that was how I always responded. Given Jonathan's own condition at the time that experience at Te Papa was also very moving; having since listened to his recent interview on Radio New Zealand's Spiritual Outlook – Facing Death programme I am in awe of Jonathan's preparedness and acceptance of his own impending departure. His confidence and self assuredness shone through stronger than ever.

— Peter Vangioni, curator, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū

I've always been too lazy and feckless to do my own thinking, so it was lucky that Jonathan had the great idea to stir me along to research the British Art Exhibit at the New Zealand International Exhibition in Christchurch in 1906-7 for a research paper at master's level in 1983. He suggested that I write a letter to the editor of The Press asking for information about private sales giving the phone number of my flat in Papanui Road as the contact. As he predicted, a great many cups of tea in Fendalton and Merivale ensued. Most of the treasure had migrated around the original families who had bought it 75 years earlier, and Jonathan thrilled to the chase as I tracked down information on the peregrinations of The Light of the World and Royal Academy bronzes. The Victorians were his passion and I can still hear his beautiful rich voice enunciating the full names of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood as if he was chanting a mantra: William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

The paper he taught with Ian Lochhead on New Zealand architecture was the making of me: I felt I had found my niche with this kind of dogged research. As a class we were let loose to make an exhibition for the Robert McDougall Art Gallery out of a bunch of architectural drawings by William Barnett Armson that had been excavated from the offices of the practice. Lyndsay Knowles showed us how to carefully clean them, Peter Ireland helped us frame them, and, with Jonathan supervising, we were allowed to arrange how we wanted them to be hung. For the catalogue, we journeyed about to Hokitika and Dunedin, poking around in archives, hoping for tender notices and other meagre gleanings to flesh out our essays. It was evidence of hard won primary research that gained Jonathan's greatest approval.

That Armson essay is still the first item on my list of publications, and lacking any originality, I set exactly the same type of curatorial exercise for my classes now. When I was floundering about looking for a thesis topic a year later, Jonathan slid the slim grey volume of Plischke's On the Human Aspect in Modern Architecture silently across his desk at me with a knowing look.

Jonathan was the only lecturer I have ever known who would invite the whole postgraduate class to dinner at his flat in Papanui Road. I remember catching sight of a little McCahon landscape as soon as the door opened and being hugely impressed. Once, on the way to the bathroom, I dared to sneak a peek at the bedside reading – the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography in Māori on Jonathan's side and Out! on Paul's. Even in bed it seemed he was the model of the serious scholar.

Jonathan was generous about sharing his knowledge. Architectural field trips were a specialty and must have been a huge amount of work to research and organise. I went on every one I could. We dubbed them Jonathons, as the pace was unrelenting and running shoes the preferred footwear – in fact, he frowned if heels were worn. No nineteenth century edifice in the South Island was safe from our investigations, and once he took us to Melbourne. But it was in Timaru that I can remember opening the door of the motel unit at 2am to a furious and pyjama-clad Jonathan who could not get to sleep for the racket we were making with our raucous partying. I took a Continuing Education group to the Sydney Biennale earlier this year, and remembering how we liked to play up as students, made sure my room was on a different floor in the hotel.

— Linda Tyler, director, Centre for Art Studies, The University of Auckland

'What is Art History?' These were the first words of my first lecture for Stage 1 Art History at Canterbury University. They were delivered – or rather, they were intoned with considerable gravitas – by Jonathan Mane-Wheoki. This was the early 1980s, and while it was another two years before I would have Jonathan as a lecturer again (for Stage 3 Victorian Art and Architecture), I've had an association with Jonathan ever since. That's what Jonathan is like; he takes a keen interest in, and stays in touch with, all his students. And while some of us have worked more closely with him over the years (once I started working in galleries he became a regular guest speaker for public programmes and at one time I worked alongside him at Te Papa), no matter how close the connection he remembers us all.

Despite knowing him for more than thirty years now, I still cannot look at him without thinking of him standing in the doorway of the Farrys motel unit in Dunedin all those years ago, in his immaculate Pierre Cardin pyjamas, telling the rambunctious students to be quiet (it was our turn to host the evening party on that Victorian architecture inspired field trip). I'm pretty sure that my peer group's Victorian costume dinner held at a friend's house to celebrate the end of the academic year, which included a vicious rewriting of the exam paper (The Pre-Raphaelites suck. Please discuss), would have done nothing to dim the grim smile of satisfaction on his face early the next morning, when he led a by now somewhat 'fragile' group of students on a vigorous and hill peppered walking tour of the city's magnificent examples of Gothic Revival and Victorian vernacular buildings.

– Elizabeth Caldwell, director, City Gallery Wellington

It's not an exaggeration to say that my life changed when I studied Jonathan's 'Worlds of Art' course at the University of Canterbury in the 1990s. Everything I had been taught or presumed was turned upside down and reshuffled. I felt as though I could see clearly for the first time how New Zealand art – past and present – fitted into a global matrix. The Anglo-American viewpoint that I took for granted was exposed for what it was – a viewpoint, and only one way of seeing the world. It's somewhat embarrassing now to admit to having possessed such blinkered cultural vision, but necessary to acknowledge, to show what a revelation the 'Worlds of Art' course was for me at that time.

Jonathan and I have kept in contact over the years. One treasured memory is accompanying Jonathan and Paul to see Isaac Gilsemans's original illustrations of Mäori in Abel Tasman's journals at the Dutch National Archives. In July this year I found myself back in the Netherlands and visited the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. I was surprised, and delighted, that the very first art work I encountered was Peter Robinson's 1996 painting Operation: Can you speak Dutch (Dutch)? Two women were standing in front of me and one was bent over trying to read the text and view the well-known Amsterdam buildings that Peter had painted upside down. The work is an Antipodean artist's take on visiting the Netherlands. Past and present jostle together, a riotous mash-up of local and exotic cultural icons and the traveller's struggle to be understood. It looked right at home. I can't help but think if Jonathan had seen it, he might have considered the pairing of Peter's painting with the Gilsemans drawing as the opening slides to 'Worlds of Art'.

I owe a debt to Jonathan. He opened a door for me into those worlds and for that I am forever grateful.

– Sarah Farrar, acting senior curator art / curator contemporary art, Te Papa Tongarewa

Kimihi te kahurangi; ki te piko tou matenga, ki te maunga teitei

Seek above all that which is of highest value; if you bow, let it be to the highest mountain

The whakatauki I have used here speaks about choosing a higher goal and not being deterred by anything of lesser importance. For me I think it fits with an ethos to do with art and art history but also in relationship to something I would write about Jonathan Mane-Wheoki.

Jonathan's contribution to art and art history for me has been his work, writing and research on the first Māori artists to engage with international modern art and the recovery of that art history. Jonathan highlighted the significance of that first generation of contemporary Māori artists in various pieces of writing over the years. One though, that stood out for me and which I have quoted and drawn on for my own thinking and understanding of the Māori modernists (a name coined by Art Historian Damian Skinner ) was his essay Te Tai Tokerau and the contemporary Māori Art movement in the book Te Puna: Māori Art from Te Tai Tokerau Northland.

Although I didn't agree to the claim in that essay of Te Tai Tokerau being 'the cradle of the contemporary Māori art movement', as I don't believe that contemporary Māori art comes out of an Iwi based paradigm, the other material featured in Jonathan's essay, the statistical information about Māori urbanisation, the dynamic created from that urban Māori diaspora, the dates and years of the Māori art specialists who were recruited for training under Gordon Tovey and his writing about artists including Ralph Hotere, Muru Walters, Arnold Wilson, Katarina Mataira, Buck Nin, Pauline Yearbury sparked my imagination and furthered my understanding of this important area of New Zealand art history. It is an essay that provided a solid base particularly in relation to the recurring exhibition I curate called Te Ao Hou, Modern Māori art for Nga Toi Arts Te Papa, which takes its name from the Māori Affairs magazine published between 1952–1976 that aimed to be a 'marae on paper'.

On a personal level, the portfolio Jonathan assigned to me when in his role as the director of Art Te Papa, acknowledged the work and focus I had always had, but also gave me global reach. It allowed me to not just be located here and concentrate on the extraordinary area of modern and contemporary Māori art but also to extend my focus to look at international indigenous art practice and histories. In 2005, it was the first position of its kind for Te Papa and was and still is an exciting proposition.

– Megan Tamati-Quennell, curator modern and contemporary Māori and indigenous art, Te Papa Tongarewa

I first met Jonathan at Ilam in 1985. He was a lecturer in the School of Fine Arts in the art history department and I was a first year student in my intermediate year at Canterbury. He was also the go-to-person in regards to pastoral care for Māori students, on all matters from course planning to study grants. Although I received no formal tutoring from Jonathan in art history, I knew of many who did, and by all accounts he was one of the best.

But more importantly for me, Jonathan represents the face of Māori academia. He has achieved success at the highest levels, both in New Zealand and internationally. A leader, a Rangatira, a mentor for aspiring Māori artists, writers, critics and curators, at a time when tauira Māori in academia needed such role models. I am honoured to have known and worked with Jonathan. Honoured that he wrote about my work, in the context of contemporary Māori art practice. Honoured to have been considered within his writings, within his unique vision of a New Zealand art history.

E te Rangatira, nga mihi nui, nga mihi aroha.

– Shane Cotton, artist

I did a BA (hons) in Art History and English Literature between 1987 and 1991. In those days you weren't shackled to a programme, so I also did bits of politics, philosophy and statistics. I was dire at all of the latter. I now teach on the Culture, Criticism, Curation course at Central St. Martins in London, and am endeavouring to finish a PhD titled '...of hesitation, delay and detour'. It has only been through these experiences that I have been able to understand the relationship between what I learnt with Jonathan Mane-Wheoki, and my lack of comprehension of the separation between what is known as 'art history', and the more recent designation of 'visual culture'.

That's because what we learnt through Jonathan's art historical perspective was always already visual culture. We learnt the idea of attempting to see, and to see particularly. Prominent in this was, of course, Colin McCahon – the simple idea that McCahon's hills always have an outline because the geographical aspect of Aotearoa is quite narrow so the sun is inevitably shining from the back of those bare hills we are shown – lit up from the backdrop of the sea. And there's McCahon's acknowledged study of geography. But there's also the fact that that this particular vision was inadvertently created by colonialism – trees were burnt down in order to make way for sheep stations, and this must have created a particular view, and indeed system, that McCahon's paintings intuit, and that Jonathan was able to make us drab undergraduates see.

– Louise Garrett, lecturer, Culture, Criticism, Curation, Central St. Martins, University of the Arts, London

Kua hinga te tōtara i te wao nui a Tāne

A great tōtara in the forest of Tāne has fallen

Jonathan was one of Aotearoa New Zealand's finest academics. He was an inspiring teacher, generous mentor, supportive colleague, world-renowned scholar, and an ambassador for every institution and organisation he served. I had the privilege of working with him at the University of Canterbury and the University of Auckland.

Jonathan's experience of art was both lived and learned. He lived in a world that was completely explicable through performance, visual arts and design. His extensive knowledge of western European art enabled him to put his distinctive stamp on the historical interpretation of our country's art. He also heightened awareness of our unique contributions to the world of art, as demonstrated through his pioneering research and teaching in Māori and Pacific art history.

He taught thousands of art, art history and architecture students. His classes were often transformational experiences. My 120 third-year architecture students were the beneficiaries of one of his last lectures, on which he was an authority, the New Zealand Gothic Revival. I had forgotten to tell him that the majority of my students were of Asian descent and born outside of New Zealand. A gifted orator, who could speak eruditely often without notes, he immediately seized on the opportunity to collapse both time and space by relating transformations in nineteenth-century Chinese religious worship to the tension between Neoclassical and Gothic architecture in contemporaneous Dunedin. As he did in all his lectures, he enabled each and every student in the class to connect with times, places and art, that they might have previously seen as remote or irrelevant. After his lecture I was inundated with essays on what seemed to be every Gothic building in New Zealand, and perplexed colleagues teaching studio reported a dramatic revival of pointed arches, buttresses and soaring vaulted spaces in student design work.

Jonathan, you have prepared and mentored the next generation of artists, art historians and curators and inspired a multitude of people from other walks of life to see the beauty in this world. As you journey back to Horeke in your waka, rest well in knowledge that we will continue your legacy.

Haere, haere, haere ra.

– Deidre Brown, associate dean research and postgraduate, National Institute of Creative Arts and Industries, Auckland

I am fortunate enough to have been part of a small bunch of young art students and recent graduates of Ilam School of Fine Arts at the start of the 1990s, who due to their lineage of Māori decent had a particular connection to Jonathan Mane-Wheoki.

The overall scene at Ilam was, and I must include the Art History students here, talent everywhere. It was of course complex in some areas but the obvious and underlining thing was the kids weren't there to fuck about – we were there to work, we were artists seeking knowledge and empowerment and the desire for that was more than you could sometimes stand. But the bottom line remained, there was stuff to get done and the good stuff was really, really great.

That was one side, another side had Jonathan and was pretty determined at finding ways to offer support – he was clearly 'on watch'. At that time you might be lucky enough to find some small putea for a few materials, hardly what you could call an unfair advantage but rather some small change to be put to good use. Jonathan formed a small group from the separately operating Māori academics, artists, and writers on campus and embraced other Māori artists in the immediate area. Around 1992 we went to Hui with Ngā Puna Waihanga at Omaka Marae in Blenheim; this was our first outing together and for this Jonathan had determined he needed baseball caps made for us all. We must have been a sight with those flash things, velvety black corduroy with 'Waitaha' in deep red embroidery – very smart, very Jonathan.

– Nathan Pohio, artist and exhibition designer, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū

There is no doubt that Jonathan inspired me in my career as an educator and then a curator and director. It is over thirty years since I attended his lectures and it was perhaps his stage three Victorian Art and Architecture paper that had the biggest impact on me. Jonathan was so passionate about his subject matter and those field trips to Dunedin as part of the course were great fun. As students on those trips we probably weren't quite as studious as we should have been. I recall him knocking on our door at Farrys Motel, in his Pierre Cardin dressing gown, instructing us to get some sleep when we'd partied too late.

Jonathan mentored a couple of generations of art historians, who benefited greatly from his wisdom and limitless knowledge. Above all else, he was always caring and professional. His visits to Tauranga in latter years demonstrated his ongoing interest in my professional career and how in his role at Te Papa he could assist a relatively new public art gallery. His mana as an art historian and teacher will not be forgotten.

— Penelope Jackson, director, Tauranga Art Gallery